The friends and collaborators catch up about the power and practicality of art.

By Ian Brennan

NPR

February 4th, 2023

Nigeria’s global star Burna Boy (center) is nominated in Grammy’s new category “best African music performance.” Nominees are from Nigeria, South Africa and Benin. Other African musicians feel neglected. Mulatu Astatke (left) is a pioneer of Ethio-jazz in Ethiopia, which has never earned a Grammy nod. North African musicians have rarely been nominated. At right: Tunisian singer Emel Mathlouthi.

The 2024 Grammy awards will see the introduction of a new category: “best African music performance.”

When the category was announced last year, Grammys CEO Harvey Mason Jr. stated that it would be “able to acknowledge and appreciate a broader array of artists” than the two existing global Grammy categories, where African artists have traditionally had the only real chance of scoring a nomination.

The actual nominees represent only three countries: Nigeria (Burna Boy, Davido, and Asake & Olamide), Benin (Ayra Starr was born there but now lives in Nigeria) and South Africa (Tyla, and producer Musa Keys, who is featured on Davido’s track).

The Academy had even specifically listed some of the genres they hoped to include in the category, from chimurenga (traditional thumb-piano music from Zimbabwe played on electric instruments) to Ethio-jazz (Amharic melodies from Ethiopia blended with 12-note jazz scales).

But only the two most mainstream African pop styles were represented — Afrobeats and Amapiano — with one nominated track even named “Amapiano,” a South African form derived from house music whose name translates roughly as “the pianos.”

And though there are an estimated 2,000-plus “living languages” across Africa, the lyrics for all seven nominated songs are either entirely in English or largely contain English words. The nominees have other commonalities. They’re all based in cities and hail from either Nigeria, Africa’s biggest economy, or South Africa, the continent’s third largest economy. Those two nations together account for nearly 20% of the nominations historically in the Grammys global categories.

The Burna Boy phenomenon

As for the category’s goal of highlighting artists in this new category who might not otherwise get Grammy recognition: Burna Boy is also nominated in the two global Grammy categories this year, plus he has a fourth nod for “melodic rap.”

And he is a true international superstar. Burna Boy, whose grandfather once managed the legendary Nigerian musician Fela Kuti, records for Atlantic/Warner Music, one of the largest record conglomerates in the world. In June, he became the first African artist to sell out a U.K. stadium— the 80,000 capacity London Olympic Stadium.

YouTube

“The commercial success of Burna Boy dwarfs that of any of his African Grammy predecessors,” says Banning Eyre, lead producer for the Peabody Award-winning Afropop Worldwide radio program and magazine. “It does raise the question of what exactly is being rewarded — artistic excellence or market success?”

Of course, that is a question that’s asked of many Grammy categories, where some artists get nominated time and time again in their respective fields — classical, jazz, rock, hip-hop, reggae, pop. We reached out repeatedly to the Recording Academy for comment; they did not respond.

Musical voices from the rest of Africa

For this story, I interviewed a number of artists from across Africa. Many of them are from the three quarters of African countries that have never seen a single nomination for their artists. In the interest of transparency, I will note that I am a Grammy-winning producer of music from Africa and other parts of the Global South. But I will not be referring to or quoting any of the musicians I’ve recorded.

Aziza Brahim, 46, a respected “desert blues” singer from the displaced Sahrawi people in the disputed Western Sahara region, says: “These two nations— Nigeria and South Africa— are not the only ones in African music. Africa is diverse in cultures, languages and music. I don’t even know Burna Boy. I’ve never listened to him.”

“I feel like there’s some laziness with the Global Grammys,” notes Emel Mathlouthi, 40, a Tunisian singer who rose to fame with her protest song “Kelmti Horra” (“My Word is Free”) when it became an anthem during the Arab Spring. “Once the Grammy voters identify an artist that works for them within the global category, then that person is gonna be present over and over and over and over. There’s not a huge effort to really be representative of diverse people globally.”

The facts back her up: For example, South Africa’s Ladysmith Black Mambazo have won five Grammys and been nominated 17 other times. Angelique Kidjo of Benin has won five Global Grammys and been nominated on 14 other occasions. And Burna Boy himself has already been nominated 10 times and won once, all in just the past four years.

By contrast, since 2008 only three new African countries have entered the list of Grammy nominees: Ghana, Malawi and Niger.

“The award is just the West’s vision of what world music or global music should be,” says Mathlouthi.

Music from northern Africa, where Mathlouthi is from, has historically been shut out of past Grammy global categories. The only exceptions are a nomination in 1996 shared by The Splendid Master Gnawa Musicians of Morocco with a U.S. collaborator, and Egypt’s Fathy Salama Orchestra winning a “Contemporary World Music” Grammy for accompanying Senegal superstar Youssou N’Dour on his victorious album in 2005.

“African music is not one style. Different countries contribute different things. The Grammy voters need to cast their net wider, they need to open their ears more,” says Zambia’s Emanyeo “Jagari” Chanda, 72. His group W.I.T.C.H.’s music has been characterized by The New York Times as “psychedelic funk with African influences.” Last year, they released Zango, a comeback album tackling topics like antisemitism and homophobia. Pitchfork wrote: “the Zamrock pioneers prove their malleable, genre-spanning style still sounds like the future.”

“These awards seem to confuse commercial success with artistic excellence and being modern,” says 26-year-old Namibian “cattle gun” singer Uakatetua, who lives in a remote village that’s a 14 hour drive from the capital city of Windhoek. (“Cattle gun” is the name of the local horn instrument he plays.)

“People consider us ‘traditional’ because we play without electricity,” says Uakatetua. “But I consider our music much more progressive than what most people from cities play.”

Widely regarded as the father of the genre known as Ethio-jazz, Mulatu Astatke, 80, is a legendary musician in Africa. He states: “I feel that the profile of Ethio-jazz and diverse African music across the world is now such that it warrants international recognition that it is not receiving at major awards such as the Grammys.” Though Ethiopia is the second most populous African nation after Nigeria, it has never had a single artist nominated.

Kenya-born “high-speed” female rapper, MC Yallah, 40, notes, “I believe Africa has a lot of great talent that’s being ignored and isn’t getting the recognition they deserve.”

Back to Burna Boy

There is no denying the popularity of Burna Boy both at home and abroad.

“Burna Boy is really amazing,” says Trustworth Samende, 36, a musician in Zimbabwe who is part of the self-proclaimed “future of Afro Sounds” guitar group Mokoomba. “But he represents a part of Africa — the West — not the whole.”

And on Feb. 4, this year’s four-time nominee Burna Boy will in minutes reach more listeners than these never nominated artists could ever dream of. He will be the first African artist to perform live on a Grammy telecast.

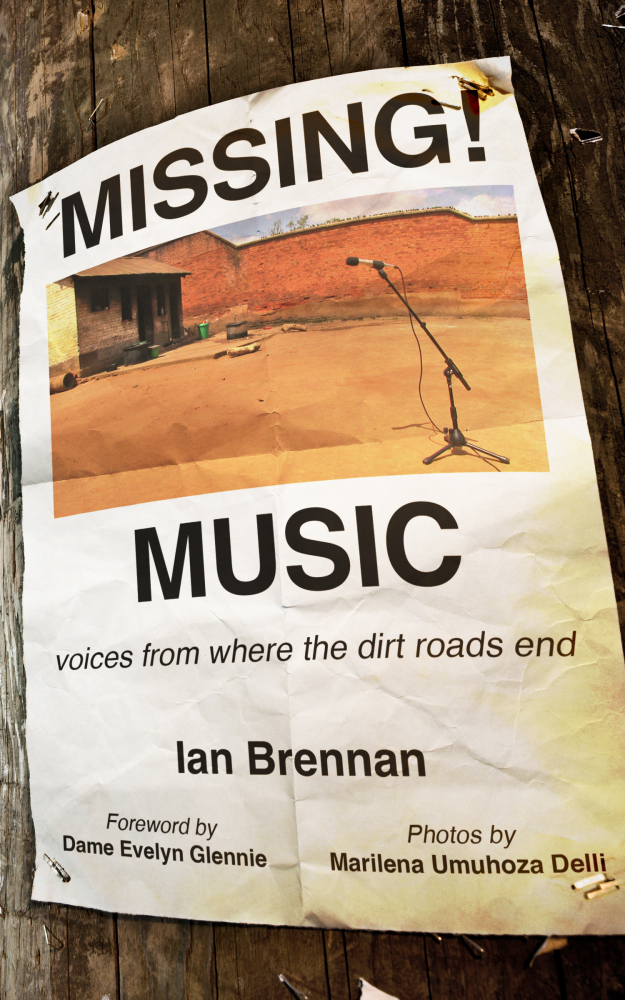

Ian Brennan is Grammy-winning music producer who has recorded over 40 albums by international artists across Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America. His newest book, coming out in March, is Missing Music: voices from where the dirt road ends.