by Jess Flarity

The FIfth Estate

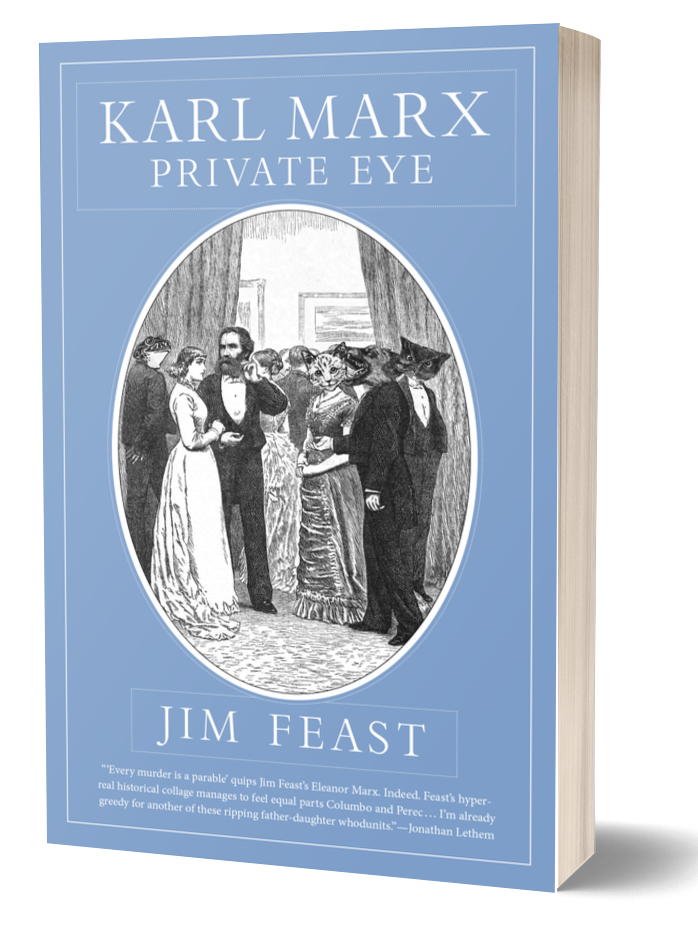

Karl Marx, Private Eye by Jim Feast. PM Press, 2023

Karl Marx Private Eye is a fascinating chimera: it is simultaneously a cozy mystery, a Conan Doyle parody, and a philosophical meditation on Karl Marx’s reaction to the failed 1871 Paris Commune.

Author Jim Feast weaves a compelling narrative that can capture the imagination of anyone who slept through most of their European Civilization 101 course. The plot rivals the twisty whodunits of Agatha Christie, while the prose feels authentically Victorian, in the line of Charles Dickens or even Charlotte Bronte, but with the pacing on fast-forward.

Set in 1875 at a spa resort in Karlsbad, Bohemia, the book weaves the tumultuous politics of the region into an oddly charming story about Marx and his daughter Eleanor as they are caught up in a murder mystery scandal. The opening chapter begins with a dream sequence, which is a technique I always give a hard side-eye to, but the echo back to the beginning from the final scenes makes this choice a satisfying one. Do yourself a favor and don’t skip to the last page: the ending is worth it.

Once the blood is spilt “black upon the marble floor” after the slaying of a maid and an American arms dealer, Feast catapults his reader into a classic detective story. His cast of whimsical characters with shady motives will leave many scratching their heads as the events unravel. Shakespeare aficionados will be especially delighted by the weaving of the bard’s works throughout the plot, with one of the folios even serving as a MacGuffin. The layers of clues and red herrings accumulate into a tapestry of wonderful confusion, though Feast’s descriptions of gore are a little R-rated for the cozy genre.

Like other mashup novels, such as Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter and Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters, Karl Marx Private Eye is a mirage that merges the real and the imaginary.

The injection of a 16-year-old Sherlock Holmes as a central character pushes the genre further into comedy, but the setting still feels grounded in the reality of history. After finishing the novel, Feast’s readers may be compelled to start googling facts about Eleanor Marx or the Serbian Independence Movement, as his mixing of fiction/truth becomes a blur.

In terms of style, the book leans more towards Theodora Goss’ The Alchemist’s Daughter rather than Jasper Forde’s The Eyre Affair, with straightforward storytelling taking precedence over outlandish metafiction. In my opinion, this makes the novel eminently more readable.

Unlike Doyle’s stories, which are almost always told from the perspective of the reliable Dr. Watson, Feast switches the point-of-view character between Marx, Eleanor, and Holmes. This choice is interesting because it gives insight into Marx’s heady lamentations, (usually not a character in real life who the Fifth Estate is particularly fond of), while Eleanor provides a refreshing feminine perspective that is all too often absent from the detective genre. Holmes’ primary function is to push the plot forward as the murderer becomes closer to being revealed. The tone shift between the three characters is surprisingly smooth, giving the chapters an addictive quality that entrances the reader to devour the novel in a single session.

Looking at writing as craft, Feast excels in concise-yet-vivid descriptions and snappy dialogue, but his use of metaphors to draw the reader into the historical period is where he is truly groundbreaking. His individual sentences remind me somewhat of Peter Beagle’s The Last Unicorn, the masterpiece fantasy novel that consistently uses animal comparisons to reinforce its more subconscious themes.

Here is just one example from Beagle that sticks to my memory: the night was cobra cold, scaled with stars. Similarly, Feast creates stunning visual imagery consistent with living in an age of emergent Victorian technology. He describes a surprised person as looking like “a cow staring at a bicycle” and often relates a character’s body position as how they would appear on a horse, such as a hilarious scene when Holmes falls halfway through a glass ceiling. These subtle details immerse the story in the Victorian perspective in a way that many may not even notice, but astute readers will find very rewarding.

A final comment worth noting is Feast’s inclusion of an Eastern perspective, in this case Chinese, towards the latter half of the book, which I will specifically be vague about here so as to not spoil the story. As with anything related to postcolonialism, this choice bears some scrutiny.

Victorian novels were riddled with anti-Eastern sentiments, perhaps most notoriously in Richard Marsh’s The Beetle, in which an Egyptian character is a literal monster, but Conan Doyle’s characters also engage in the passive racism associated with the English upper-class. If Feast includes a Chinese character and gives them a voice in his story, is this helping correct the damaging history of Britain’s colonization, or is it simply a form of pandering?

Like his inclusion of Eleanor’s point-of-view as a nod towards feminism, I think Feast is at least trying to break many of the destructive cycles associated with the detective genre itself by giving Eastern voices their own space rather than ignoring them entirely or stereotyping them, so I applaud him in this regard.

It is important to remember that Karl Marx Private Eye is primarily a comedy. Doing a Marxist analysis of the book and pointing out how characters like Holmes, or even Marx and Eleanor, are members of the bourgeoisie on a spa vacation, yet also our protagonists and heroes, is at best near-sighted, and at worst, self-destructive.

Holmes cooperates and receives assistance from the police to solve the murder mystery—does that make it “copaganda?” I don’t think so. Rereading the book using different analytical lenses may reveal that Feast is doing more than simply following genre conventions and is perhaps subverting them in unique ways that we have never seen before.

In Karl Marx Private Eye, Feast has captured the spirit of the 1871 Communards while still holding the attention of a modern audience. To discover all the secrets of the novel, you will need to pick up a copy and sleuth through them yourself, becoming, as Marx would have wanted, the product of your own labor.

Jess Flarity writes frequently for the Fifth Estate.