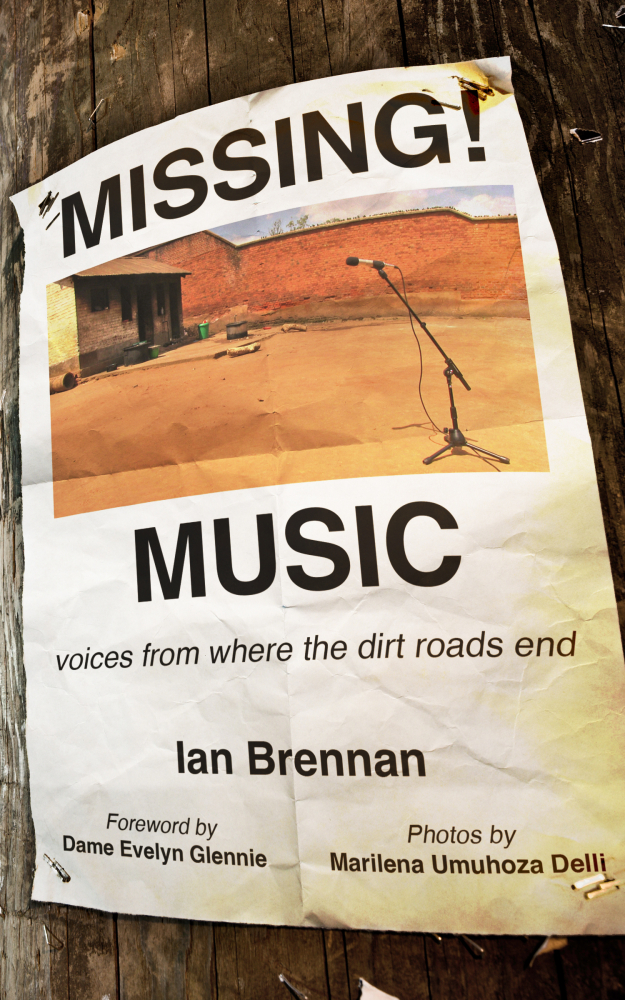

Powerhouse producer-writer’s ninth book, ‘Missing Music’ tells far-flung tales of preserving essential voices.

by Joshua Rotter

48hills

September 26, 2024

On Mon/30 at City Lights, when Ian Brennanappears in conversation with musician Peter Case to plug his latest book (more info here), he swears he won’t steal the spotlight.

“We’re just going to have a conversation,” says the Grammy-winning music producer and author of this year’s Missing Music: Voices from Where the Dirt Roads End. “When I do book events, I prefer to interview the person and talk about music and their writing or music.”

That must be challenging when living such an interesting life.

The Oakland native, who grew up in Pleasant Hill before moving to San Francisco in 1991, originally worked multiple jobs—psychiatric counselor, violence prevention educator, radio host, and music writer—to support his singer-songwriter ambitions. He has nine albums under his belt to prove it.

But realizing his greater talents lay in production and promotion, he put his musical dreams aside to amplify the voices of other artists.

Brennan began by hosting a free, mostly acoustic music show at SF’s BrainWash laundromat (1996-2001), featuring local bands and resulting in three aptly titled Unscrubbed compilations (1997–1999).

From there, he went on to produce Grammy-nominated LPs for Ramblin Jack Elliott and Peter Case, and in recent years, a “sonic memorial” for those who perished on the streets titled Homeless Oakland Heart.

He’s also organized benefit shows featuring marquee names like Merle Haggard, Kris Kristofferson, Fugazi, Sleater-Kinney, and Green Day—and continues to produce John Waters’ live comedy shows.

But since 2010, the SF expat, who relocated to Italy after losing his Potrero Hill apartment to an owner move-in eviction, has gone global, spotlighting the work of underrepresented artists in such “peripheral” nations as Rwanda, Malawi, Kosovo, South Sudan, São Tomé, Romania, Comoros, and Vietnam. His work on Tuareg-Berber band Tinariwen’s Tassili earned the producer the 2011 Grammy for Best World Music Album.

The longtime music writer continues to publish books about these endeavors. Missing Music, his ninth, collects the latest narratives from his field-recording treks to Botswana’s elderly shamans, Azerbaijan’s centenarians in the Talysh Mountains, and Bay Area’s disabled Sheltered Workshop Singers. These often forgotten communities are brought to life through gripping stories—and accompanying photos from his wife, Marilena Umuhoza Delli.

“I never was interested in being famous or rich,” says Brennan. “I just wanted to participate in bringing beautiful things into the world. And if that’s other people and supporting others instead of me being the front person, that’s fine.”

I spoke to Brennan about his labor of love, the challenges on the road, and the importance of everyone’s voice being heard.

48 HILLS Your earlier books were about anger and trauma. Your fourth book, How Music Dies (or Lives): Field-recording and the Battle For Democracy in the Arts, is the first where you explore some of the topics in Missing Music. Why make this switch in subject matter?

IAN BRENNAN I wrote two books on anger because that’s what I’ve been teaching about for 31 years, which makes it possible to do these money-losing labors of love with international musicians in less economically advantaged countries. Then I wrote a music book and didn’t think I’d ever write another one. Then I wrote another and another—and then I wrote this latest one. The core of it was the stories of these experiences with these incredible artists and musicians worldwide.

48 HILLS Many of the stories take place during the pandemic. How did you navigate these work trips during the global emergency?

IAN BRENNAN So 2021 to now, we have had a flurry of activity because when things reopened, shut down again, and then reopened, we knew we had to do this while we could. But it made a lot of those trips much more complicated and expensive than they would be normally. When we went to Rwanda during that period, we had to be tested five times for COVID.

There’s a lot of change after lockdowns, and we saw some of the devastation, particularly when we visited the elders, the centenarians in the Talysh Mountains. We went up into the mountains and talked to people. Eventually, somebody would say, “There’s this woman that’s 100-plus years old. She lives in the next village. And the next village is usually not far as a crow flies.”

But it’s all muddy dirt roads and mountain roads and took half an hour to an hour or more to get from one village to another. A lot of that trip was really sad because when we got there, they’d say, “They just passed away a couple of months ago.” That happened over and over again.

Fortunately, we were able to meet a lot of people who survived and were incredible singers and storytellers. But that was reflective of that era. If we’d gone there to make the record a year or two earlier, it would have been a very different experience.

48 HILLS How does your work teaching violence prevention worldwide connect to championing underrepresented musicians? Does music ever enter your violence-prevention work?

IAN BRENNAN Art at its best is social work. Sadly, most mass media is instead just social engineering. We have a moral responsibility to listen carefully to the least heard and turn our focus away from those screaming for attention that tend to dominate the discourse.

48 HILLS Your wife, Marilena, travels with you, photographing the artists you record and write about. As an Italian-Rwandan and antiracism advocate, how has she raised your awareness of sociopolitical issues?

IAN BRENNAN Marilena’s mother lost her entire immediate family in the 1959 and 1973 genocidal massacres in Rwanda, attacks that were overlooked internationally. That generational trauma is something we are forced as a family to deal with daily to varying degrees.

Marilena founded the first BIPOC-owned anti-racism academy in Italy and does amazing work in schools to help decolonize Italian history. One of the biggest obstacles in confronting discrimination is to do so within a culture that fundamentally believes that they are “not a racist country.” Somewhat paradoxically, the prognosis for improvement is usually far better when there is more self-awareness about existing prejudices and inequities—even if they are worn proudly—rather than reflexive defensiveness and denial.

48 HILLS Speaking of prejudice,you wrote a 2019 opinion piece for the Chicago Tribune criticizing the racist and misogynistic lyrics of The Rolling Stones’, “Brown Sugar,” and calling for the band to cease playing it live, which eventually happened. With so many misogynistic and racist songs out there to single out, why “Brown Sugar”?

IAN BRENNAN A lot of it was that they had the biggest tour that year. It was a current issue. It wasn’t something buried in the past like “Sweet Home Alabama” that just played on the radio. But I wasn’t into canceling at all. I was saying, “Retire it from your live set. That’s it.”

The band’s origins have many complex relationships to race and appropriation and The Rolling Stones wrote many incredible songs regardless of how they came about. But it seemed absurd that these millionaires in their seventies were celebrating such racist tropes nightly in football stadiums full of people.

48 HILLS What do you hope people take away from your work?

IAN BRENNAN To have true global democracy every nation and language must have a voice. The oft-repeated cultural hype is that barriers between musical genres have broken down in recent years, but in fact, what has largely occurred is simply greater homogenization—one big saccharine mush. Most genres have become more slick and crassly commercial, and are virtually indistinguishable from one another.

Ninety percent of streaming activity goes to one percent of artists. At a time when it’s easier to listen to more sonic and linguistic diversity than ever before, the majority of listeners are doing the opposite. Corporations have never possessed greater monopolization of media than they do now. America is one of three countries exporting more music than they import.

Diversity should not be distorted and disguised as simply swapping out the frontpeople for capitalism. Someone from South Korea or Lagos, riding around in a Maserati and singing songs in English about consumption or making narcissistic boasts is a mockery of what true representation and inclusion could look like. As always, it is those most vulnerable economically that are invisibilized and denied as a result.