Photo by Charles Russo

By Alex Shultz

SFGATE

December 29th, 2022

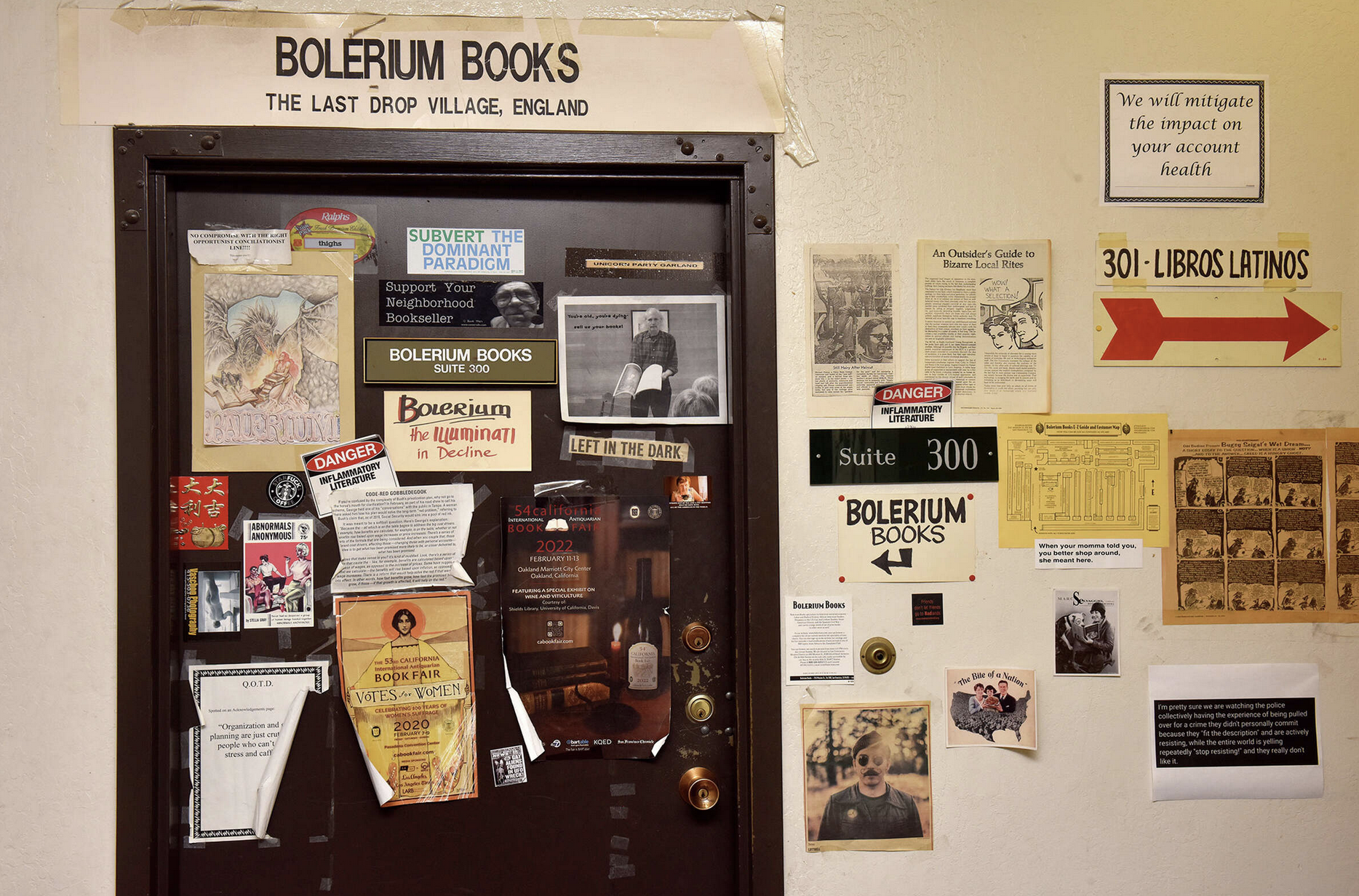

John Durham and I are sitting across from each other at Bolerium Books, a leftist staple that’s occupied the third floor of an unassuming building in San Francisco‘s Mission District since 1985. A co-owner since the beginning, Durham has seen, and learned, quite a lot here — both from the store’s wide-ranging collection of books and artifacts and from the whiplash-inducing clientele who’ve stopped by to poke around.

To sum up a day in the life, Durham relays an anecdote: “A cop and a minister walk into a bookstore …”

He pauses, assuring me this isn’t the setup to a punchline. The minister was looking for introductory literature about Marxism; Durham wasn’t sure why he had a cop with him. The two approached Durham to ask for help. He’d be right with them, he replied, before turning back to the customer who’d gotten to him first: an English professor-turned-tattoo artist, who was interested in exploring the shop’s collection of trans pornography.

“If you wonder why my mind gets warped, now you know,” Durham laughs.

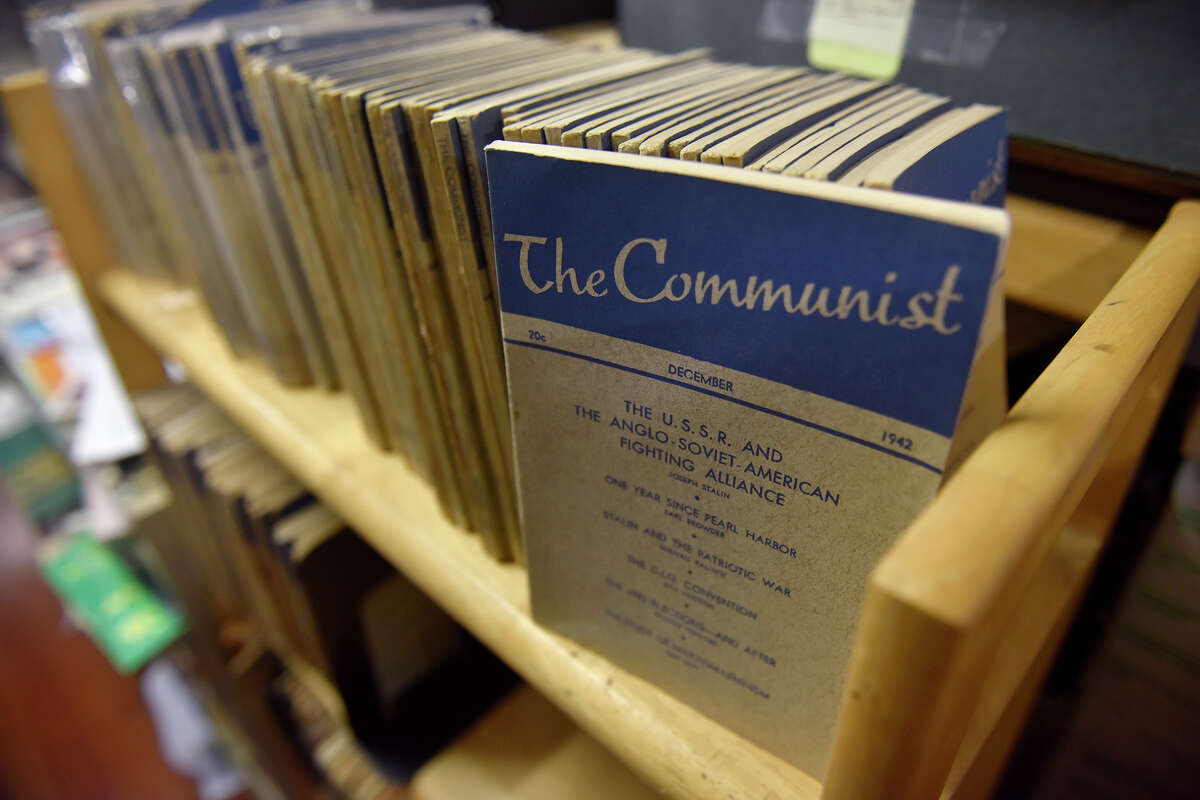

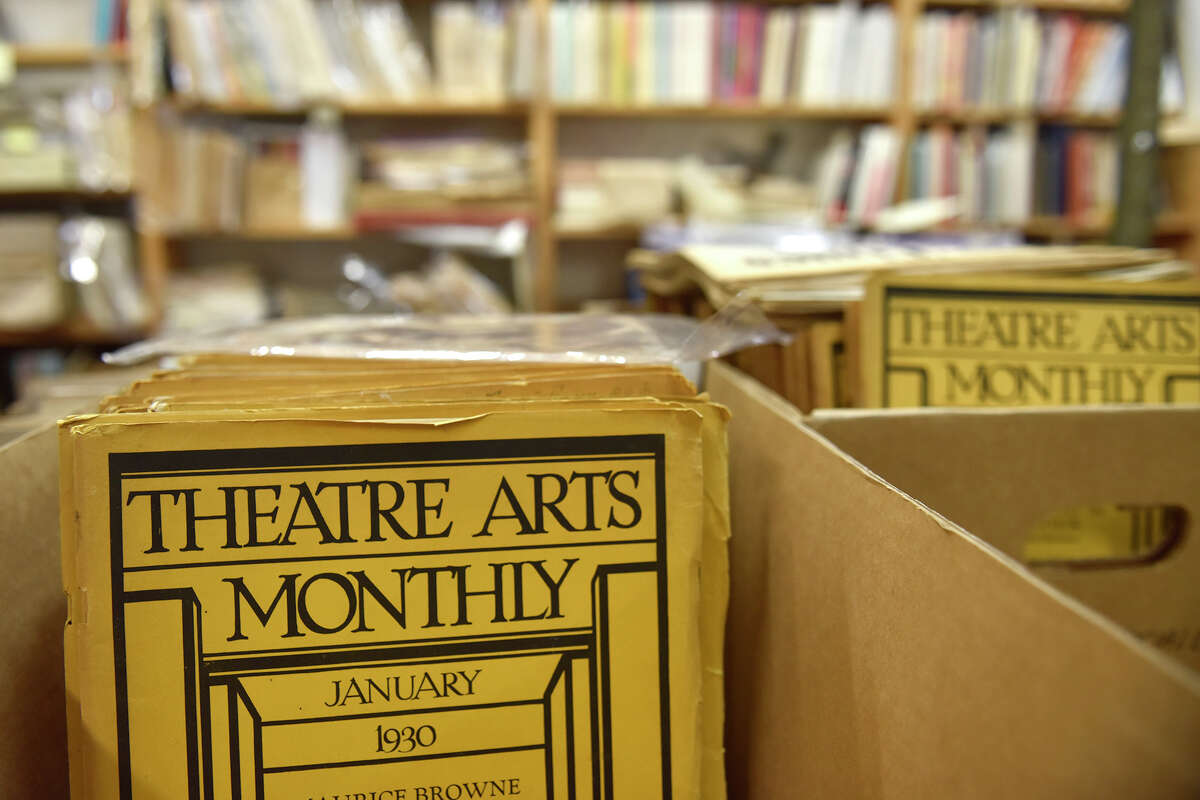

Last month, I toured Bolerium, a thriving, decades-old bookstore with no sign out front, invisible to passersby. Bolerium’s ever-expanding database houses roughly 74,000 titles, with an emphasis on social movements, especially American labor and radicalism. These days, most of the bookstore’s customers shop online; since the pandemic, visiting the store in person has required an appointment. Even pre-pandemic, Bolerium got by mostly on word-of-mouth and mail orders. Perusing is welcome, including for Marxist-curious ministers, but only if you understand what you’re getting into.

“The stuff we do is so obscure,” Durham tells me. “Your average person isn’t going to know what to make of it. We want to basically appeal to people who are really interested in our catalog and really want to learn or already know quite a bit and want to expand their knowledge. We’re not set up for a general storefront.”

Durham is now 70 years old, with a boyish haircut, a deep, reassuring voice, and a fondness for messing with people. Before visiting the shop, I read in several news stories that Durham never tells the truth about why the store is called Bolerium. Indeed, when I ask, he tries to convince me it’s the name of a furry rodent in ancient Rome.

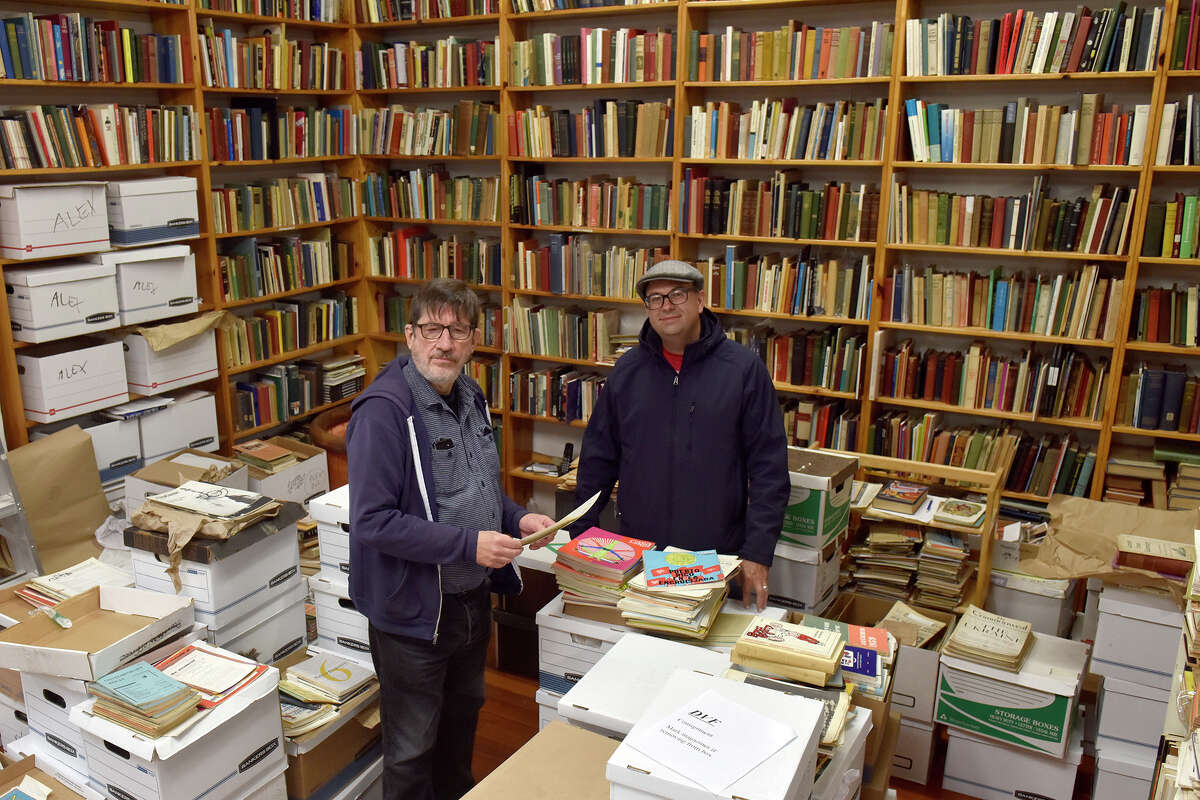

Another co-owner, Alexander Akin, is also in the shop when I visit. Under pressure, he gives up the goods. “It was an old name for a place in Cornwall that basically means ‘land’s end,’” he tells me when Durham isn’t listening. Bolerium Books first launched as a mail-order catalog in 1981, and it kept its collection in a former co-owner’s home, near San Francisco’s Lands End. The Mission location eventually opened in ‘85.

Akin, 48, tells me he first wandered into Bolerium as a customer in 2007 and loved the place so much that he started taking on little cataloging assignments for Durham. By 2013, having earned Durham’s trust (and a Ph.D. in East Asian languages, literatures and linguistics), Akin decided to buy in as a co-owner.

When Durham — and his co-founder and partner, Sue Englander — first opened the Mission shop, it took up one room on the third floor. As their collection has grown by the tens of thousands, Durham and Englander have leased out more and more rooms. They now occupy almost all of the third floor. Other co-owners have come and gone; Durham and Englander own 80% of the business, and Akin owns 20%, with the plan being that Akin will slowly buy Durham out.

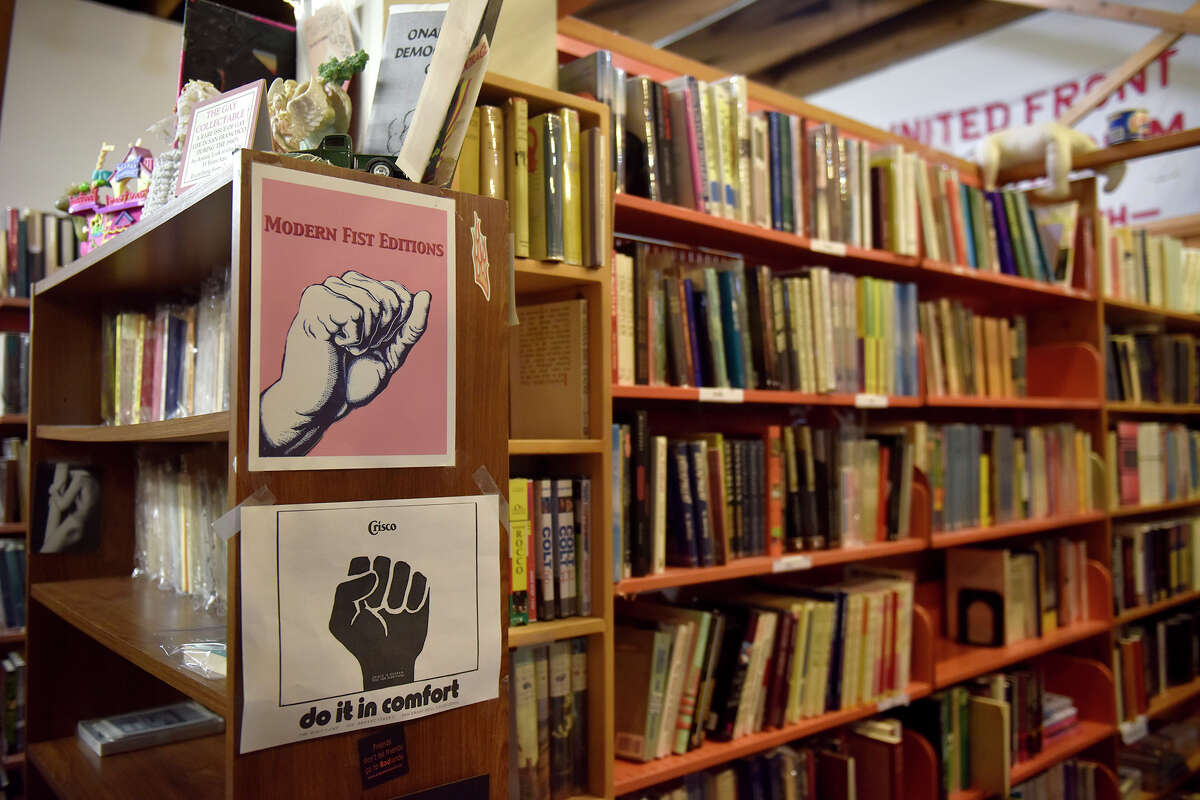

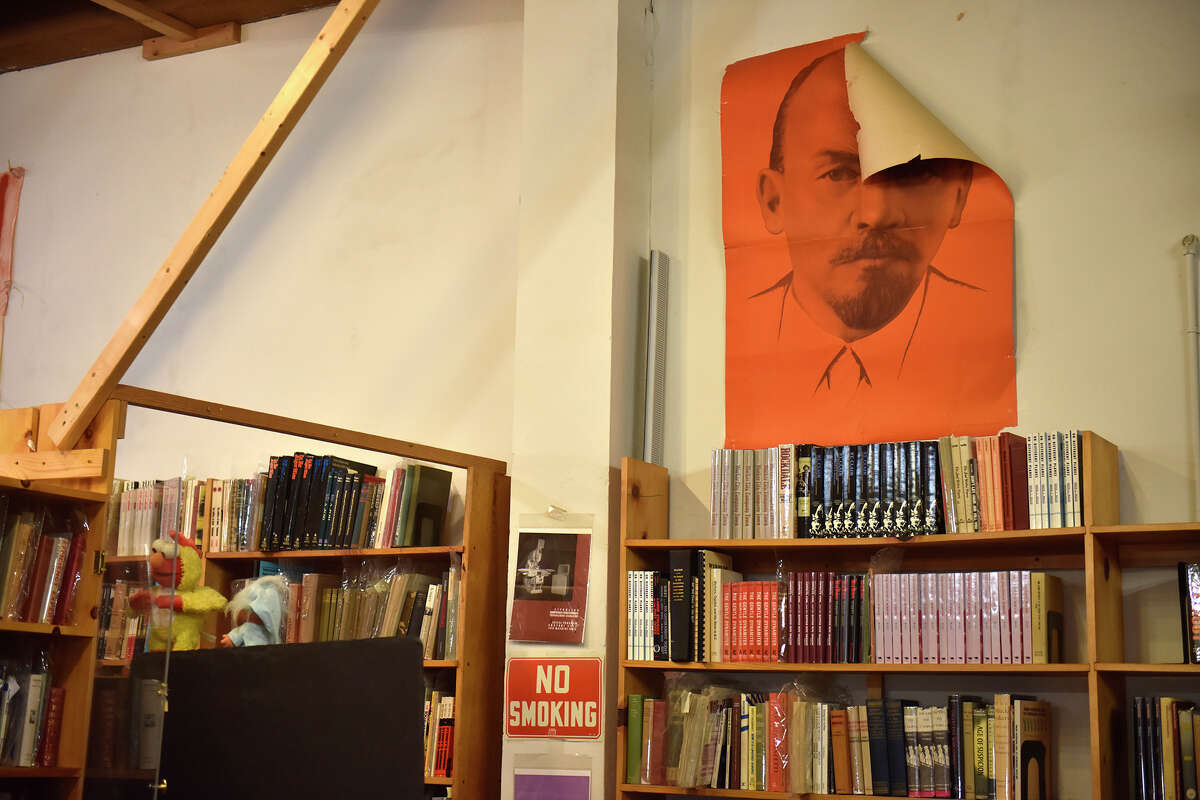

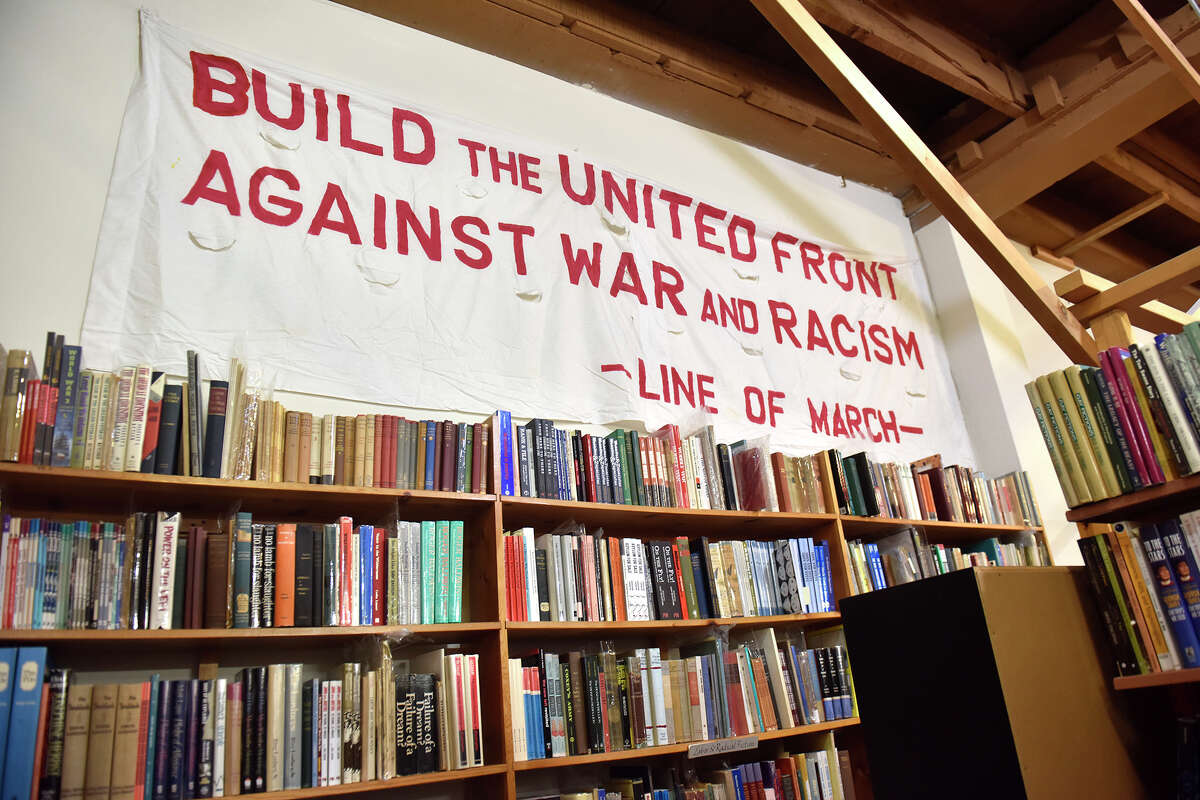

When potential patrons make an appointment, they’re typically allowed access to the main room. It’s musty, dusty and rickety; the walls are adorned with protest flyers, communist relics and ephemera. Titles are chaotically sorted by approximate subject matter. Both subtle and not-so-subtle jokes abound; the “gay” section is marked by a penis necklace and a sign that reads “modern fist editions.”

Interior views of Bolerium Books, at 2141 Mission St., in San Francisco. (Charles Russo/SFGATE)

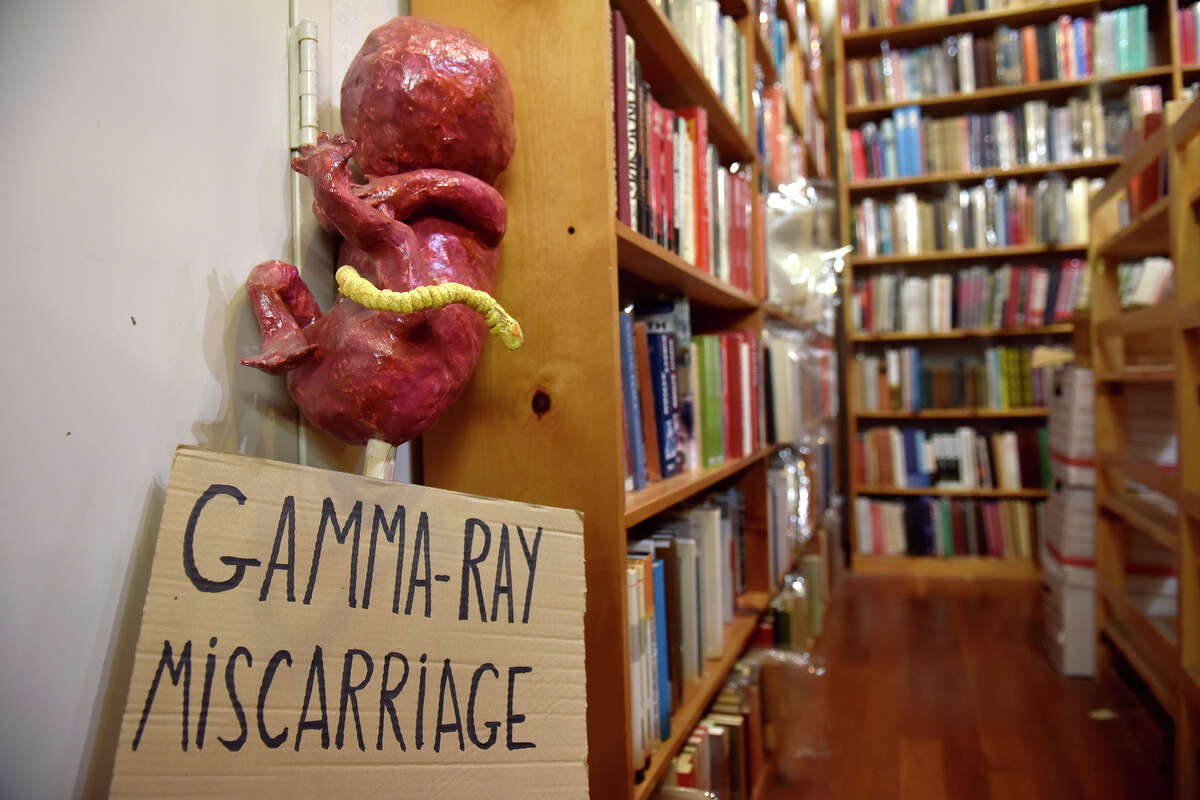

After getting my bearings, Durham diligently walks me aisle by aisle. There’s a section dedicated to Black history in America, along with a lesbian section that spins off into a deep collection of lesbian pulp novels. Then there’s the sexology section, where Durham keeps the “boring straight stuff.” The back walls are dedicated to American labor movements and radicalism. Above the shelves, a poster of Lenin is slowly peeling off the wall. Durham shows me a plastic fetus on a stick, labeled “gamma rays miscarriage,” which came from some long-forgotten protest at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; it’s for sale, should anyone be interested.

We venture into another room, where racks and racks of books consigned in recent years await cataloging. It’s Akin’s job to look through them and decide where they go. “There’s enough in here to work on for the rest of my life,” he says.

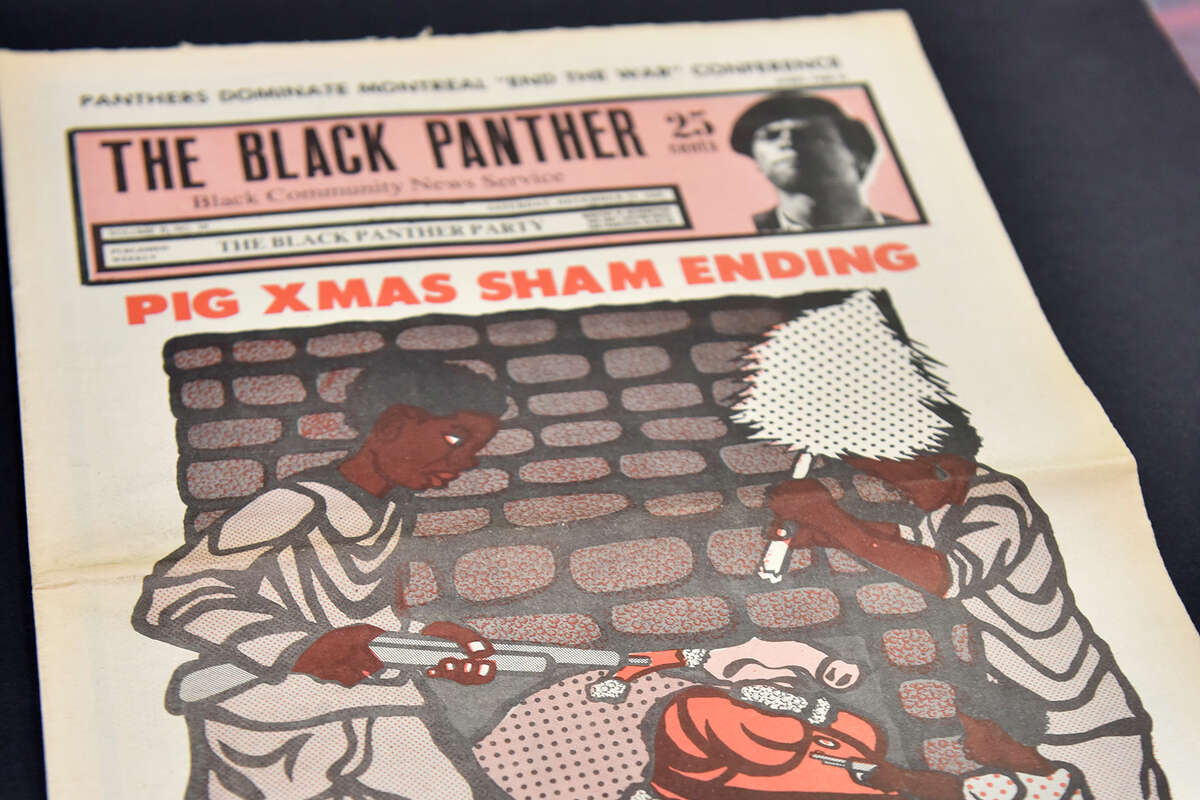

In preparation for my arrival, Akin has set aside some notable artifacts, including a 1968 Christmas-themed sketch from revolutionary artist Emory Douglas, who frequently drew illustrations for the Black Panthers’ Oakland-based newspaper. In the newspaper issue Durham shows me, Douglas drew a Black family standing around a fireplace, pointing weapons at a human-looking pig dressed as Santa Claus. Across the top of the paper reads “PIG XMAS SHAM ENDING.”

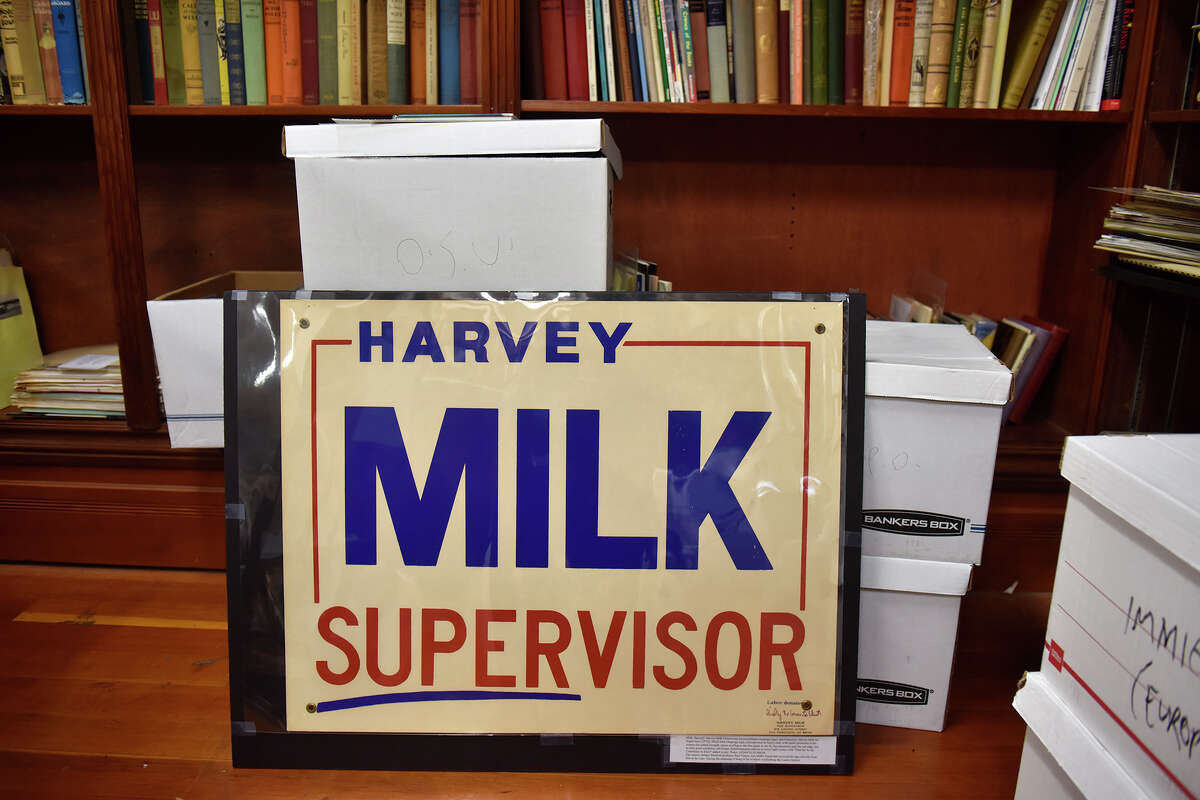

Bolerium Books features a wide range of rare items for sale, such as a copy of the Black Panthers’ 1968 Christmas newspaper edition, left, and an original poster for Harvey Milk’s city supervisor campaign, upper right. (Charles Russo/SFGATE)

“There was a real political point to it,” Akin says of the piece. “When people are shopping for the Christmas season, really, this is taking money out of the Black community and putting it into department stores and so on.”

Next, Durham pulls out some posters of Harvey Milk. They knew each other a bit; Milk was a “nice guy,” Durham tells me, who “swore up a storm in City Hall,” a trait he found “impressive.” Durham wasn’t — and still isn’t — fond of Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who became mayor after Milk was assassinated.

“I am proud to say I have never ever voted for her,” Durham says. “I’ve never quite forgiven her for never going to any [Pride] parades because she’s deeply worried she’ll encounter a cute naked man.”

In the 1970s, Durham protested against the Vietnam War and for gay rights. Like Milk, he organized against the 1978 Briggs Initiative, a homophobic California ballot measure that would have banned LGBTQ educators from teaching in California schools. Durham was also an honest-to-goodness “paid agitator,” though it wasn’t nearly as glamorous as Tucker Carlson makes it seem. Durham mostly remembers going from door to door at college campuses and getting tossed out of dorm rooms for trying to spread the gospel of the Young Socialists Alliance, a Trotskyist youth group that funded the trips.

“I can tell you one thing: It’s a remarkably ineffective activity,” he jokes. The “pay” was food money.

We head to the shipping room, where Durham and his core staff put together mail orders for their digital customers, including libraries and rare book collectors. “We try to keep our stuff fairly reasonably priced so that people that actually work for a living can afford it,” Durham says.

Every week, Bolerium sends out emails about new arrivals to category-specific email lists. Especially juicy new listings are often snatched up within minutes. “The really hardcore book collectors keep their ears to the ground,” Durham says. In total, Bolerium usually receives between 50 and 80 orders a week, which are mailed out on Thursdays.

Bolerium has fulfilled orders for plenty of unexpected clients, too. Glenn Beck once ordered some old newspaper clips tied to the Weathermen, a radical group from the ‘70s. Another time, the FBI ordered a book about the FBI.

Wandering around the mailroom, which is itself lined with many shelves of books, I stop at a section anointed “The White Problem.” It’s mostly right-wing authors and includes the eye-catching title “Making Chastity Sexy.” I ask Durham why he collects so much material he clearly disagrees with. “You know, I’m not for whitewashing history,” he says. “You have to stare it in the face, the ugliness of parts of American history. … It teaches you that as crazy as the far left can be, it’s a lot saner than the far right.”

After the tour, we find a place to sit, and Durham tells me more about his life. He’s resided in the Mission since the mid-1980s. He’s hardly an activist anymore, he tells me, spending far more time with his books than on the streets. “I’m up here on the third floor dealing with the past,” he says.

Durham knows Bolerium will never be a tourist attraction like City Lights or even a destination for the average reader. And yet, for its core clientele, Bolerium remains an institution — and a sanctuary — no matter how the city of San Francisco changes outside its walls. For Durham, that’s more than enough.

“When I moved here in ’85, I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, wow, I’m opening to the public,’” he tells me. “I was thinking, ‘Wow, I’ve got a place to put my books.’”

Bolerium Books, 2141 Mission St., Suite 300. To schedule an appointment or search its catalogue, visit the Bolerium website.