Introduction

Subvertising is a term that covers a set of tactics, such as billboard revision, projections and brand-busting, which allow campaigners to replace and hijack corporate and government imagery to share a very different set of messages.

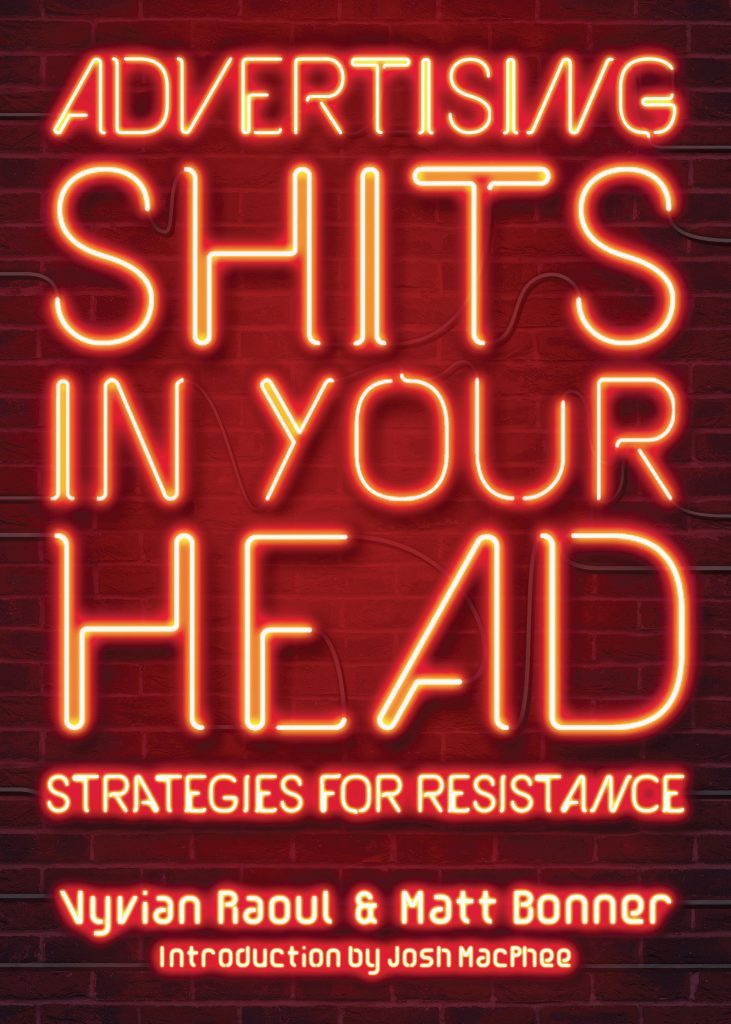

In Advertising Shits in Your Head: Strategies for Resistance (PM Press, 2019) Vyvian Raoul and Matt Bonner expose the manipulation and damage wrought by the advertising industry and outline the ways in which subvertisers are fighting back. The following excerpts from the book include a discussion of the history and practice of subvertising as well as a case study regarding the group Brandalism.

Book Excerpts

Today, the practice of subvertising is reaching novel heights. Collectives are starting to connect globally to form an ever-increasing force of resistance against the visual and mental implications of advertising. Initiatives such as Brandalism, Brigade Antipub and Plane Stupid are beginning to specifically address the connections between advertising, fossil fuels and climate change. Intervening into advertising spaces that usually celebrate consumption, they divert messages towards ones of anti-consumption. – Thomas Dekeyser, 2015

“Subvertising,” a portmanteau of “subversion” and “advertising,” can be defined as any type of action that subverts advertising. This may range from improvised graffiti-style interventions, to the more coordinated campaigns of the modern era. Generally speaking, subvertising either targets the original adverts or the sites of outdoor advertising (or both).

Though it is difficult to say when exactly subvertising emerged as a form, the history of organised outdoor advertising subversion dates back to at least the 1970s. In 1977, the Billboard Liberation Front (BLF) was formed in San Francisco and began setting about making what they termed “improvements” to outdoor advertising, as well as encouraging others to do the same. The Australian BUGA UP (Billboard-Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions) collective started taking direct action against tobacco advertising in 1979 (because, in their words, “someone had to do something about it!”) and claim to be one of the first groups to use the term “subvertising.” Both of these organisations still have websites that reflect on their history and give advice to potential practitioners.

© Brandalism

The motivations for subvertising have traditionally been wide ranging— from objections over individual products to aesthetic concerns, direct action to simple mischief. Though the strategies of altering, removing, or reversing outdoor advertising may remain largely the same, today’s subvertisers are a more coordinated movement, with a more connected vision:

The method is the most interesting part of Brandalism, since it’s specifically designed to confuse the viewer a little. This is why the posters are usually playful, typically mimicking established designs. They are, I think, motivated by 1960s French Situationism— people who believed the culture, the ‘spectacle’ of modern society needed to be attacked, and done in such a way that would wind up, rile, mimic, anger, confuse. – J Bartlett, 2015

Subvertising is a distinct form of culture jamming—an attempt to “intervene in the visual landscape that shapes how we think.” It has a direct link to the work of the Situationist International (SI); in particular, subvertising can be thought of as a form of “detournement”—a rerouting or hijacking of capitalist messaging—a tactic that was pioneered by the SI. This is true in terms of the aesthetic subversion of brands and their adverts, but also in terms of the physical hijacking of advertising spaces, or “takeovers.”

One way that subvertisers claim this form of detournement may work is by intervening in the visual landscape to puncture the “existing regime of truth.” As described earlier, outdoor advertising occupies an elevated position; by both intervening in the physical space containing the advert and altering the messaging, subvertisers hope to displace “an already-established disposition”—to disrupt our habitual ways of thinking.

A criticism of subvertising is that overemphasising its potential effect may be naïve. As academic Richard Gilman-Opalsky points out: “Debord was well aware, in the 1950s and 60s, that something like sporadic ‘subvertising’ could never jam a culture of constant accumulation. Subvertising at its best is like a skip on a record that the needle passes over with a minor interruption.”

It’s possible that subverts may just be ignored or subsumed into habitual ways of thinking; it’s also true that just as advertising works in a cumulative way, subvertising is most likely to be effective as part of a sustained campaign, rather than individual takeovers.

Neither can subvertising call for reform if it is to be considered detournement, in the Debordian sense. Protest art academic Catherine Flood claims that Adbusters “shifted the focus of graphic resistance from creating radical alternatives to mainstream design and advertising to exposing and attempting to reform its practices.” The modern subvertising movement seems to have returned to the original Debordian critique of the spectacle, a critique that is suspicious of reform: “One must not introduce reformist illusions about the spectacle, as if it could be eventually improved from within, ameliorated by its own specialists under the supposed control of a better-informed public opinion.”

© Brandalism

In addition, where Adbusters took aim at individual brands and campaigns, even if this could be seen as part of a more systemic critique, it fired from a relatively elevated position. It did not attempt to pass the weapons around or bring in new recruits— those who aren’t able to take part in the fight are necessarily relegated to the position of spectator. The modern subvertising movement attempts to mobilise these previously passive spectators and place them at the heart of the fight.

Case Study: Brandalism

Bill Posters started his art life as a graffiti-writer, tagging roofs, trains and walls as part of a crew whilst at university. After becoming more politicised by the Iraq War, he ended up writing his dissertation on culture jamming, referencing Lefebvre, Klein and the Situationists, and says this acted as the “anti-business plan” for what became Brandalism.

The first Brandalism project in 2012 had billboards and consumerism as its target, and saw Bill recruit a friend (who is still part of the anonymous Brandalism crew) to help with the installs. Though the billboards caught the attention of much mainstream media, the billboard twosome quickly realised that they were “just two blokes in a van.” Since then, their focus has been on empowering others to take their own actions, and every campaign since has seen more and more volunteers get involved.

Bill Posters sees the work of Brandalism—replacing adverts with art—as a gift. Unlike advertising, it demands nothing of the viewer and can be viewed as a two-way interaction. Internationally acclaimed artists have featured in the Brandalism projects—Peter Kennard, Gee Vaucher, Robert Montgomery—but on the street they’re presented anonymously.

Brandalism 2012

The first Brandalism project happened in July 2012, across five major cities. Two installers pasted up 36 large-format billboards (48-sheets) with original work from 28 international artists. The project was deliberately timed to coincide with the “protective brand-mania that characterised the London Olympics” and as such gained international media attention, provoking “a discussion about the legitimacy of outdoor advertising spaces that we are forced to interact with.”

Brandalism 2014

Concerned that there were questions over the democracy of the project, Brandalism prepared for round two with a three-day training course on both the theory and practice of subvertising. Ten crews from all over the UK attended and collectively helped to select and print the artworks that would be installed on the streets. Over two days, 365 artworks were installed in bus-stop-sized advertising panels in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Brighton, Bristol, Oxford and London. The installs again included work from internationally acclaimed artists but were again anonymised.

Brandalism 2015

The Paris project was in support of protests against the COP21 conference and attempted to make the connection between consumerism and environmental destruction explicit. In particular, the project took issue with what they saw as greenwashing of the climate talks.

Increasingly, these talks [were] dominated by corporate interests. This year’s talks in Paris are being held at an airport and sponsored by an airline. Other major polluters include energy companies, car manufacturers and banks. Brandalism aims to creatively expose this corporate greenwashing. -Brandalism, 2015.

The Brandalism crew were in Paris for two weeks leading up to the day of the action, where they printed off the 600 posters which would eventually be installed. During this time they also made tools for accessing Parisian bus stop cabinets and trained local teams in the art of installation. Despite Paris being under a state of emergency with all street protests banned, Brandalism pulled off their biggest takeover to date and garnered international mainstream attention for their efforts.

Switch Sides

A day of international action against advertising had been called by French subvertising group RAP and, in response, Brandalism created their Switch Sides campaign. Posters were designed that specifically addressed the workers from top ad agencies Ogilvy Mather, ABDO, and WMT, and then installed outside their offices in Manchester and London. A link was printed on the posters that took users back to the Brandalism site and a short article explaining why they thought that people who work in the industry ought to switch sides: “We installed those designs in Manchester and London to start a conversation with you. Congratulations on making it into one of the country’s top advertising agencies. We were triggered by a particular concern: that your talent, energy and creativity is sinking into an ever expanding black hole. Your creativity could mean so much more.”

© Brandalism

Access Book

Advertising Shits in Your Head: Strategies for Resistance includes further case studies regarding advertising and its opponents, as well as tactical guides, and can be purchased here.

Book Overview

“Advertising Shits in Your Head calls adverts what they are—a powerful means of control through manipulation—and highlights how people across the world are fighting back. It diagnoses the problem and offers practical tips for a DIY remedy. Faced with an ad-saturated world, activists are fighting back, equipped with stencils, printers, high-visibility vests, and utility tools. Their aim is to subvert the adverts that control us.

With case studies from both sides of the Atlantic, this book showcases the ways in which small groups of activists are taking on corporations and states at their own game: propaganda. This international edition includes an illustrated introduction from Josh MacPhee, case studies and interviews with Art in Ad Places, Public Ad Campaign, Resistance Is Female, Brandalism, and Special Patrol Group, plus photography from Luna Park and Jordan Seiler.

This is a call-to-arts for a generation raised on adverts. Beginning with a rich and detailed analysis of the pernicious hold advertising has on our lives, the book then moves on to offer practical solutions and guidance on how to subvert the ads. Using a combination of ethnographic research and theoretical analysis, Advertising Shits in Your Head investigates the claims made by subvertising practitioners and shows how they impact their practice.” (Source – Publisher’s website)

Explore Further

- 5 lessons for success from real-world #BrandJam campaigns

- Unhealthy Promotions (BUGA UP) campaigns against tobacco advertising, Australia, 1978-1994

- Creative activism 101 An antidote for despair

- How Artistic Activism can move us Toward a Better Future

- Creative Activism: Start Here

Advertising Shits in Your Head calls adverts what they are—a powerful means of control through manipulation—and highlights how people across the world are fighting back.