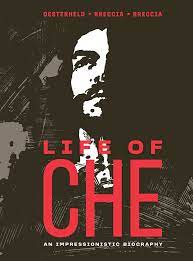

A review of Life of Che: An Impressionistic Biography by Héctor Germán Oesterheld, Alberto

Breccia, and Enrique Breccia (Fantagraphic Books)

The story of this book is almost as extraordinary as the story of Che Guevara’s life. As explained

in the afterword by Pablo Turnes, Vida del Che was first published in January 1969, two years

after Guevara’s death, by Argentinian publisher Jorge Álvarez. At the time, Argentina was ruled

by a military junta, so publishing a biography of a revolutionary in the form of a graphic novel

was itself a revolutionary act.

To secure the safety of everyone involved in the publication, Álvarez released the book under a

fictional imprint called Ediko and offered to remove the author’s and artists’ names from the

cover. The writer, Héctor Germán Oesterheld, courageously left his name on the jacket (and

would later be “disappeared” by the government in 1977 at the age of 58). The book sold out.

In 1973, the military junta raided the publisher’s offices and destroyed all evidence of Vida del

Che’s existence. It wasn’t until 1987 that the book was salvaged, in Spain, from a printed copy.

Clandestine editions and translations followed (this reviewer picked up a copy in Portuguese

from a Lisbon street market in 2019), but never in English until now.

As the subtitle states, Life of Che tells Guevara’s story impressionistically. The text is a mixture

of newspaper clippings, diary entries, invented dialogue, and literary flourishes. The key

episodes of Che’s life—his childhood, his motorbike trip across Latin America with Alberto

Granado, meeting Fidel Castro in Mexico, and scenes from the Cuban Revolution and its

aftermath—are interspersed with his fateful (and fatal) campaign in Bolivia. The narrative

switches between first and third person.

Memorable lines abound. The motorbike trip—Che’s revolutionary awakening when he was still

a medical student—concludes with “The diseases he really wants to cure aren’t typhus, malaria,

leprosy, but hunger, exploitation, injustice.”

There’s also a healthy dose of wit in this telling. After the Cuban revolution, we are treated to

the irony of Che, a man who cared nothing for money, being named Director of the National

Bank of Cuba. He’s depicted showing up to work in his fatigues, a machine gun at his side. He

signs documents “Che.” The look on the faces of the bank officials as they contemplate him is

priceless.

The abiding tone of Life of Che, however, is pathos. Once Che realizes that “those who reduced

everything to economics were wrong . . . [t]he true revolution can only occur within the heart,”

he decides to take up arms again and writes a moving farewell note to his children. In it, he

refers to himself in the past tense: “Your father was a man who acted upon his beliefs” and

exhorts his children to “be always able to feel in your depths any injustice committed in any

part of the world. It’s the most beautiful quality of a revolutionary.”

From here on, the story has a trajectory as fixed and inevitable as a Greek tragedy. We know,

and he knows, he’s doomed. Toward the end, as he regards his sleeping comrades-in-arms in

Bolivia, he notes, “A life given for something is never lost.” But the cartoon panels grow darker,

and the text dwindles until words slip away altogether.

While the storytelling is impressionistic, the artwork, by father and son Alberto and Enrique

Breccia, is pure expressionism. Black ink sprawls across white backgrounds; silhouettes and

shadows recur; and Che’s iconic features emerge from tangled roots and bunkers. Ink spatters

conjure spilled blood.

The use of woodcuts, too, chimes perfectly with its subject matter. The technique, associated

with early 20th century leftist artists—socialists and anarchists—lends a purity of form, almost

abstract in its blocky simplicity, to the episodes on the battlegrounds of Bolivia.

The final three pages of Life of Che are extraordinary. They unfurl like a roll of film, gradually

zooming in on the murdered Che’s visage, crosshatched like scars, with a bullet hole above his

right eye. That visage stares back at its viewers, daring us to take up his unfinished

revolutionary mission.

JJ Amaworo Wilson