by Joanne McNeil

Columns, Issues

Apr 14, 2022

In 1968, Judith Merril and Kate Wilhelm planned to run an advertisement in a science fiction magazine with a list of authors announcing their opposition to the Vietnam War. But when they reached out to fellow members of the Science Fiction Writers of America to add their names, Merril and Wilhelm were shocked. There were significant numbers of vehement pro-war authors in the community, and they also wished to share their views with the science fiction-reading public.

When the advertisement ran in Galaxy Science Fiction, it covered two full pages. On the right, the names of authors including Ursula K. Le Guin, Philip K. Dick, Thomas M. Disch, Samuel R. Delany and dozens more appeared under the statement “We oppose the participation of the United States in the war in Vietnam.” On the page to the left was another list of names, including Robert A. Heinlein, Leigh Brackett, Jerry Pournelle and Jack Vance, the undersigned who believed “the United States must remain in Vietnam to fulfill its responsibilities to the people of that country.”

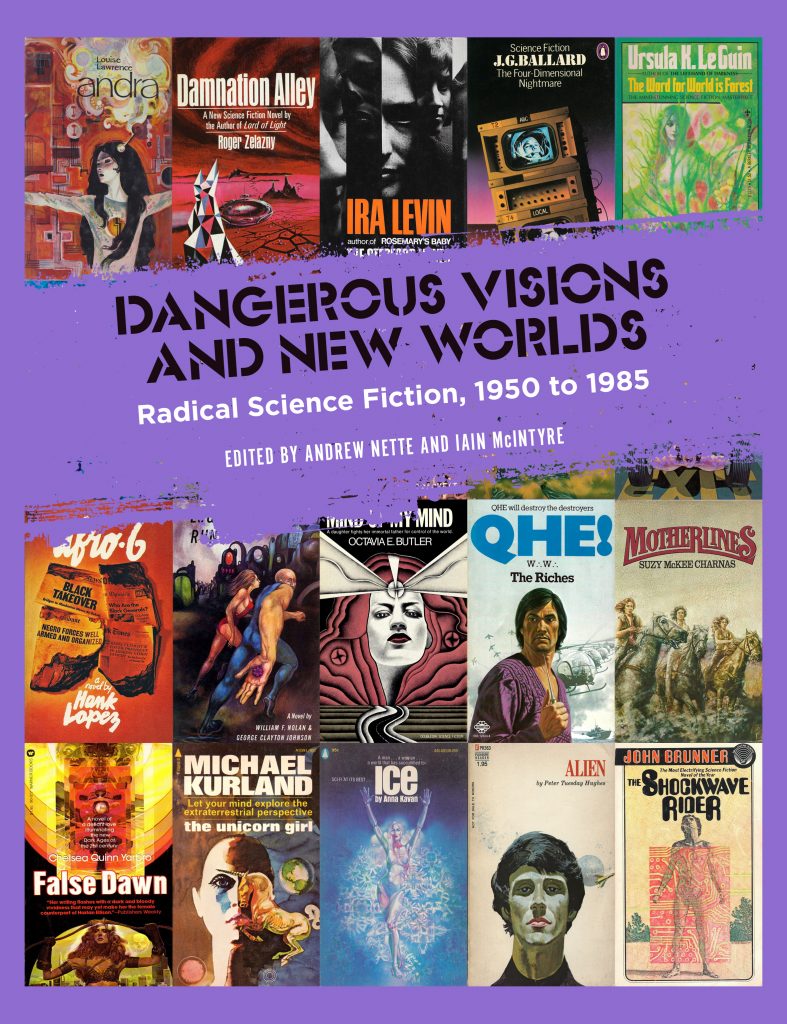

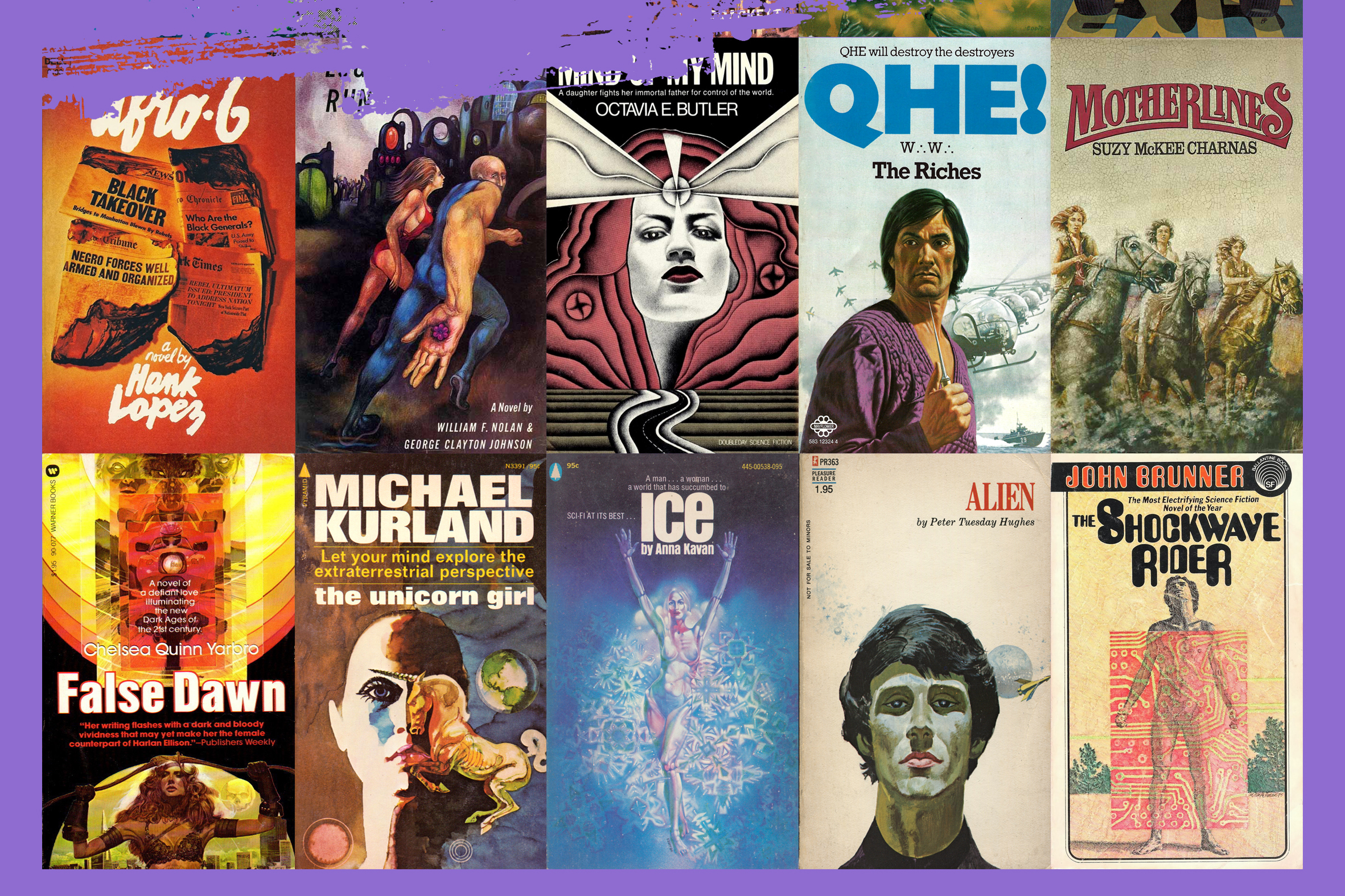

While there were more traditional science fiction writers in the anti-war section, like Ray Bradbury, Gene Roddenberry and Isaac Asimov, the two petitions broadly signaled a generational split: “Golden Age” science fiction and the writing that happened next. The legacy of those who departed from the mainstream continues to this day, but at the time, these writers were emerging and relatively obscure: Le Guin published her first novel two years before, and Delany was only 26 years old. Science fiction, to these writers, was the “ideal vessel for […] refusal of established power and social relations,” Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette write in the introduction to a new anthology they edited, Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1985. In the wake of Hiroshima, and as outer space became a frontier for the Cold War, these writers understood that scientific breakthroughs could be militarized. They were concerned with threats to the environment, and their stories were more likely to explore technology as a ruinous force, as well as address issues of race, class, sexuality and gender. Unlike the Golden Age gee-whiz stories of white male heroes conquering space and solving problems with gizmos, theirs was science fiction infused with the counterculture’s “pansexuality, communal lifestyles, hallucinogens and radical politics.” An outlaw sensibility runs through the work featured in the book—which ranges from genius to campy—and audiences were receptive to it. Even the most extraordinary and strange writing could be commercially successful (Delany’s Dhalgren, for example, has sold more than a million copies). The breadth of this anthology underscores what unites these disparate authors: Each writer expanded the genre itself and what material might be considered “science fiction.”

Key figures featured in the book have strongly influenced writers and filmmakers working today. The Babadook director Jennifer Kent is working on a project based on the life of Alice Sheldon, who wrote science fiction under the pen name James Tiptree Jr. The influence of Ira Levin, author of The Stepford Wives and Rosemary’s Baby, is apparent in Jordan Peele’s films. Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” adapted into the film Arrival, appears heavily influenced by Delaney’s Babel-17, and the author studied with Disch at Clarion, the revered science fiction writing workshop. Contemporary writers, including Neil Gaiman and China Miéville, speak frequently about the influence of the “New Wave” on their work.

Likewise, Octavia Butler has ascended from cult writer to legend in our time. The author, profiled by Michael A. Gonzales in Dangerous Visions and New Worlds, wrote far-out science fiction in an “earthy and grounded” style. Butler was shy, dyslexic and thought to be “slow” as a child by her teachers; in adulthood, she worked minimum-wage jobs and was a self-described hermit. But she contained universes and flourished on the page, dazzling readers with her confident yet unpretentious voice, her humane gift for rendering complex characters and the sheer marvel of her imagination. Butler wrote about racism and structural inequalities with force as the most prominent Black woman science-fiction writer of the era. In recent years, Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower has come to be regarded as a twentieth-century speculative classic on par with George Orwell’s 1984 and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. The novel movingly depicts community resilience during societal collapse with startling prescience, including a fascist leader who pledges to “make America great again.” The author hit the New York Times Best Seller list for the first time in 2020 with Parable, and A24 has a film adaptation in the works, with Garrett Bradley set to direct. That’s just one of a number of Butler projects, which also include Wild Seed, in development with Viola Davis’s production company, JuVee, and Dawn, with Ava DuVernay’s ARRAY Filmworks. A series based on Butler’s Kindred is forthcoming from FX, with a pilot directed by Janicza Bravo.

The influence of Damnation Alley—both the 1969 Roger Zelazny novel and its loose film adaptation, directed by Jack Smight in 1977—is explored in an essay by Kelly Roberts. The novel is a blend of Hells Angels culture, western and nuclear holocaust tale. Like its contemporaries Mad Max (1979) and A Boy and His Dog (1975), adapted from the 1969 Harlan Ellison novella, it presents the desert as a natural post-apocalyptic backdrop. The premise, in which a criminal is offered a full pardon if he should successfully make his way through a wasteland and save the world, likewise influenced Escape from New York (1981). The “Landmaster” created for the film is a fully operative vehicle that is regularly displayed in car shows—when it isn’t parked in the lot of a Southern California auto body shop as a roadside attraction. Tesla’s Cybertruck looks like it was drawn with the vehicle’s menacing geometric form in mind.

The title Dangerous Visions and New Worlds is a nod to two notable publications of the era: the magazine New Worlds, edited by Michael Moorcock from 1964 onward, which published edgy, genre-crossing material by J.G. Ballard and others, and the two Dangerous Visions anthologies edited by Harlan Ellison. (A final installment, The Last Dangerous Visions, announced in 1973, has become legendary for its lengthy and rancorous delays—even after Ellison’s death in 2018, his estate has claimed it will still be published.) Norman Spinrad, quoted in the book, says that in the Golden Age, science fiction was “edited as if it were stuff for teenagers, or more accurately, what librarians thought teenagers should be able to read.” Ellison and Moorcock, however, were open to experimentation and wild ideas as editors.

But the next generation wasn’t a free-for-all, either; Moorcock was clear about what he didn’t want. In his 1977 essay “Starship Stormtroopers,” the New Worlds editor identified the “crypto-fascists” from which his writers had made a break: “There is Lovecraft, the misogynic racist; there is Heinlein, the authoritarian militarist; there is Ayn Rand, the rabid opponent of trade unionism and the left, who, like many a reactionary before her, sees the problems of the world as a failure by capitalists to assume the responsibilities of ‘good leadership’; there is Tolkien and that group of middle-class Christian fantasists […] To all these and more the working class is a mindless beast which must be controlled or it will savage the world.”

The Golden Age “didn’t have a function; it wasn’t attacking much,” Moorcock said in February 2022, when he appeared at a virtual symposium for the anthology hosted by the City Lights Bookstore. “We were trying to change science fiction to something that was more political,” the author Marge Piercy said on another panel, noting that she was first drawn to the genre as a college student in the 1950s. “We thought we were all going to die,” she said, and science fiction, unlike “mainstream literature,” addressed these anxieties.

Our present—the future in these books cited in Dangerous Visions and New Worlds—is no utopia. Piercy, in her 2016 introduction to Woman on the Edge of Time, says that in the years since her 1976 novel was published, “inequality has greatly increased […] more people are poor, more people are working two or three jobs just to get by.” But the genre itself has improved in time: These writers expanded our imaginations and forged a path for intergenerational fellow travelers.