N.O. Bonzo’s illustrations, murals, and literature build on radical art traditions, addressing relations of labor and identity in local communities and protest movements.

Support Hyperallergic’s independent arts journalism. Become a Member »

Anarchist illustrator N.O. Bonzo produces decentralized media in a highly bureaucratic cultural landscape. Their illustrations, murals, and literature emerge in unexpected places, from the streets of Portland, Oregon, to the far ends of Reddit and Twitter, addressing relations of labor and identity in the workplace and on the streets.

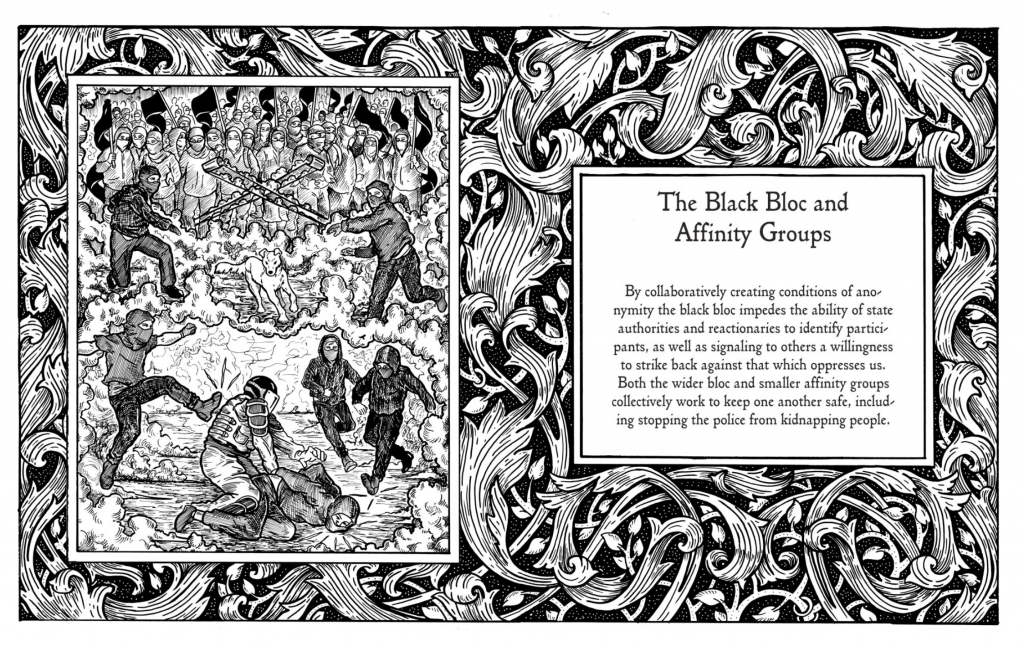

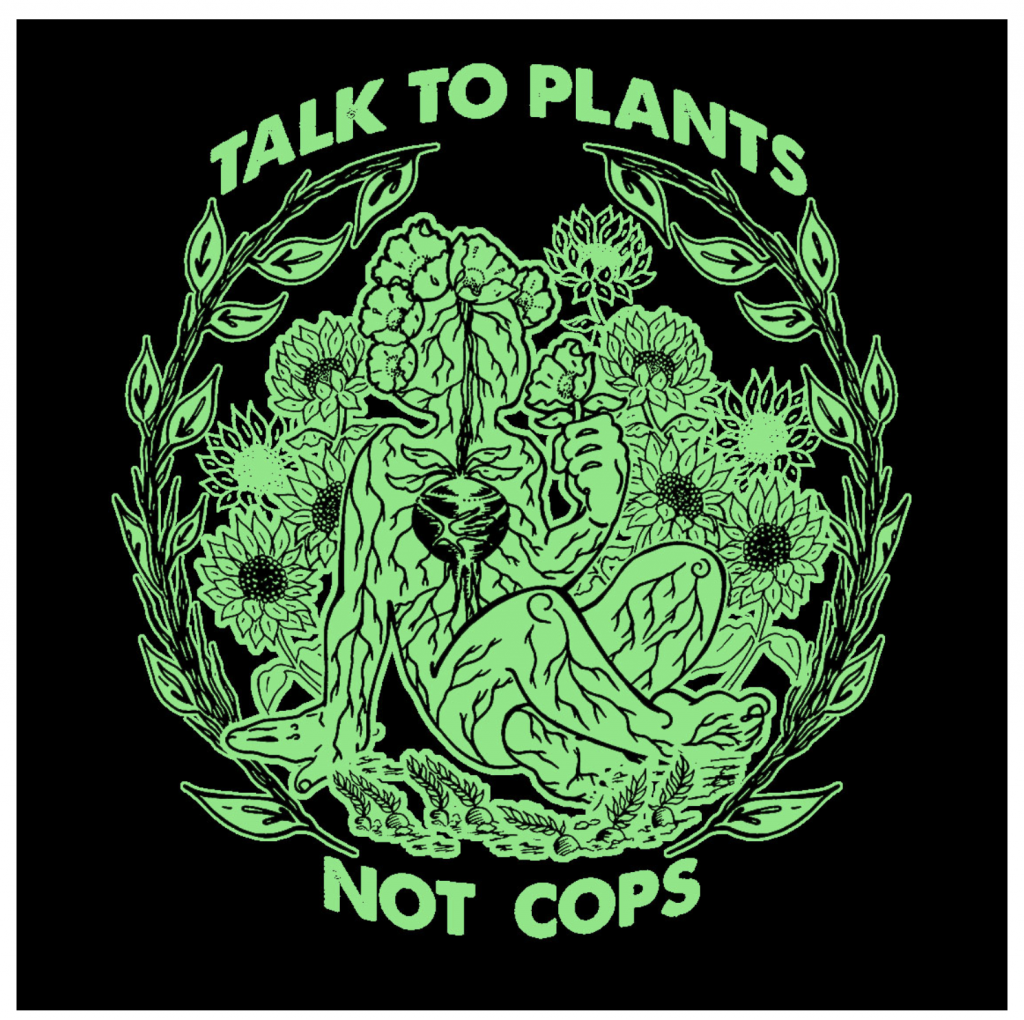

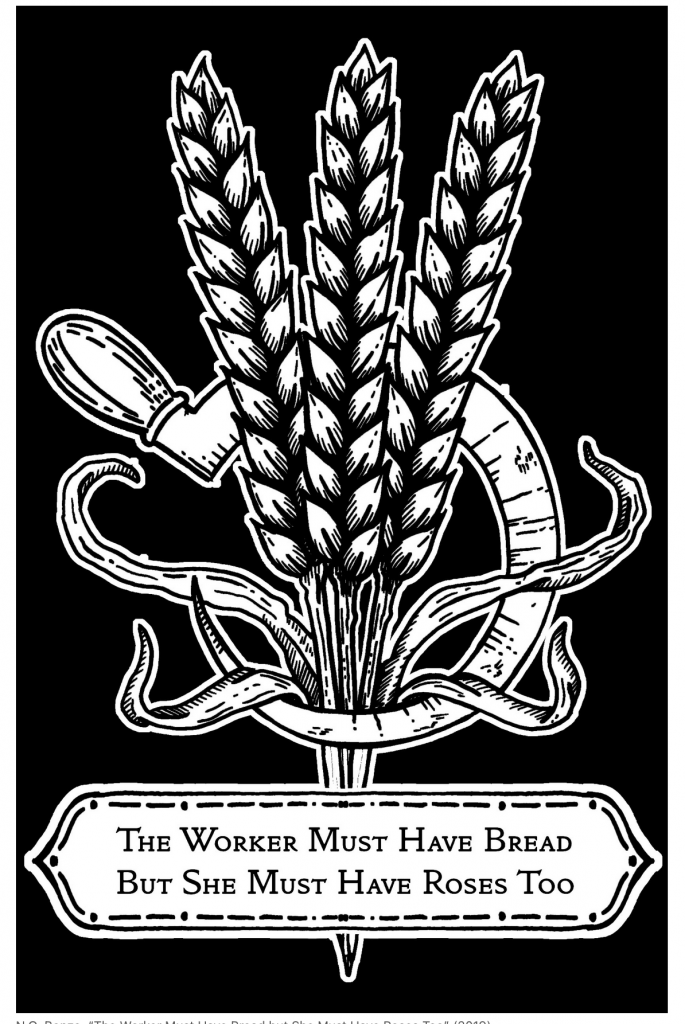

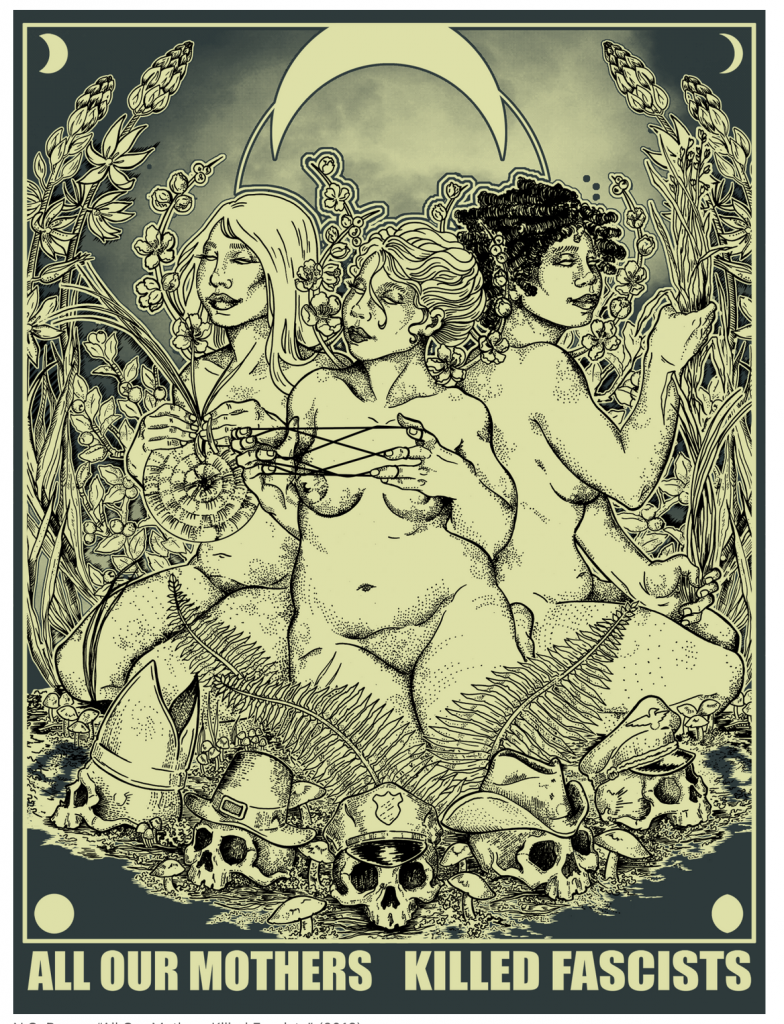

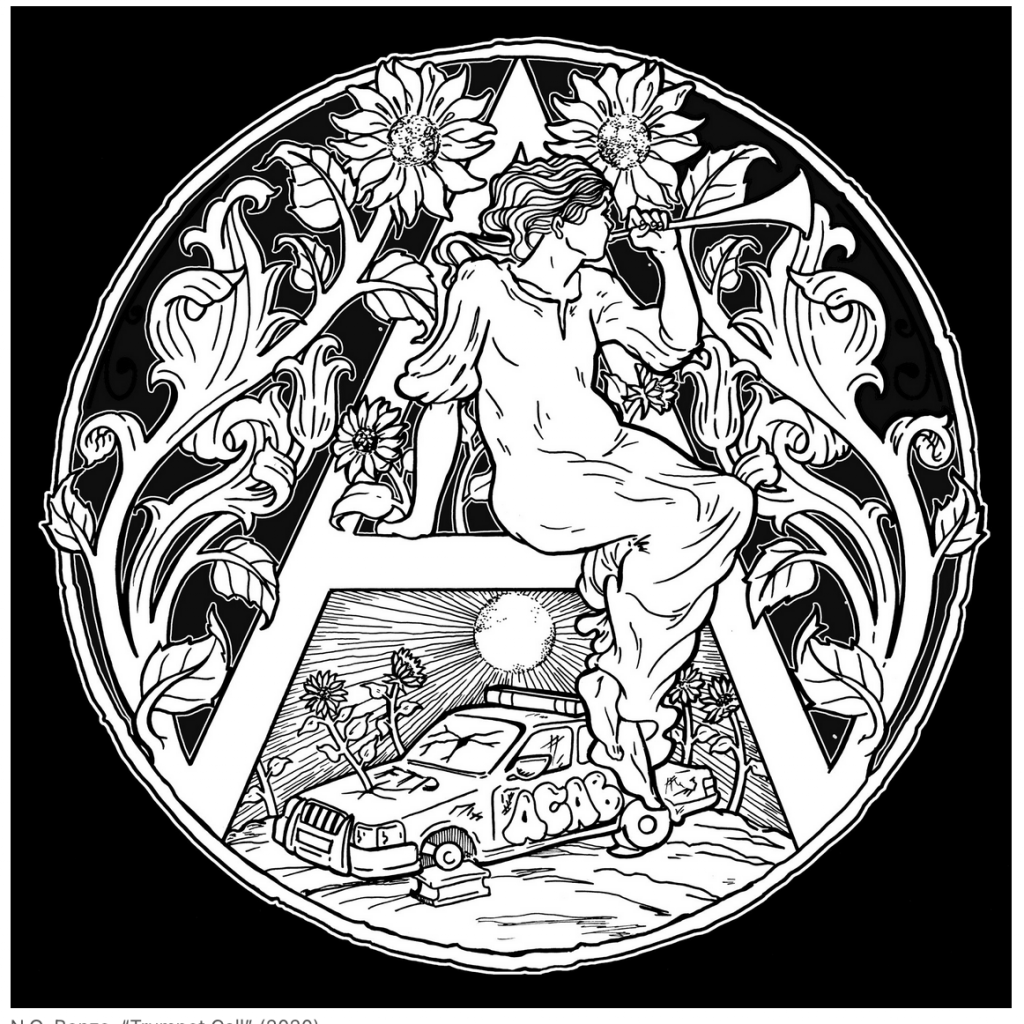

Growth and care are central themes that manifest in bodies made of leaves, workers tilling the earth, and black bloc protestors breaking police lines. Each artwork sends a clear, bold message with luminous imagery against black backdrops. Detailed figurations of families and comrades appear energetic yet intimate, occasionally juxtaposed with destroyed cop cars and smashed Nazi regalia.

Channeling monochromatic designs of early 20th-century political cartoons and woodcuts, Bonzo builds on radical traditions with graffiti elements, union symbols, queer erotica, and everyday people living under police and border surveillance. Printmaking allows the artist to reproduce and distribute their art quickly and across an array of media (e.g., posters, banners, clothing, and stickers), reflecting a desire to break what they call “little fiefdoms of privatized technical knowledge.”

“Art placed within its own sphere as an institution separated from everyday life was and continues to be an assault on the creative spirit — the alienation of creation from life,” Bonzo told Hyperallergic. “Often when you talk to people about how they were drawn to anarchism, they identify subcultures within punk or hip-hop. These spaces are incredibly rich and saturated with expression, much of which is not necessarily going to be identified as art or end up in a gallery or museum.”

With PM Press, Bonzo has published the Everyday Fire May Day Zine! — which depicts animals dancing around a bonfire of riot gear — plus an antifascist coloring book and illustrated reissues of Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902) and The Great French Revolution (1893). Bonzo complements the Russian historian’s words with images of riots and food pantries, adapting histories of community organizing to the abolitionist movement today.

Influenced by DIY art communities, Bonzo claims that shared values create common aesthetics. This can be seen, they assert, not just on punk house walls or stick-and-poke tattoos but in organizing against racism and dispossession. In this way, their work is internationalist, expressing solidarity with all who oppose capitalism and the far right worldwide.

“Having public spaces that have strong visible showings of art and projects which explicitly state anti-racism as a value, which utterly reject transphobia, that celebrate and value dignity and compassion — these can be the signposts and signals for the scenes or communities that work to disrupt fascist organizing,” they said.

Bonzo posits that abolition is not the destruction of society but its rebirth. In the spirit of late author David Graeber, their art portrays the world as “something we make, and could just as easily make differently.”

A selection of N.O. Bonzo’s work can be found on their website, Etsy shop, and PM Press.