By Marie Kelly

Workers World

February 10th, 2021

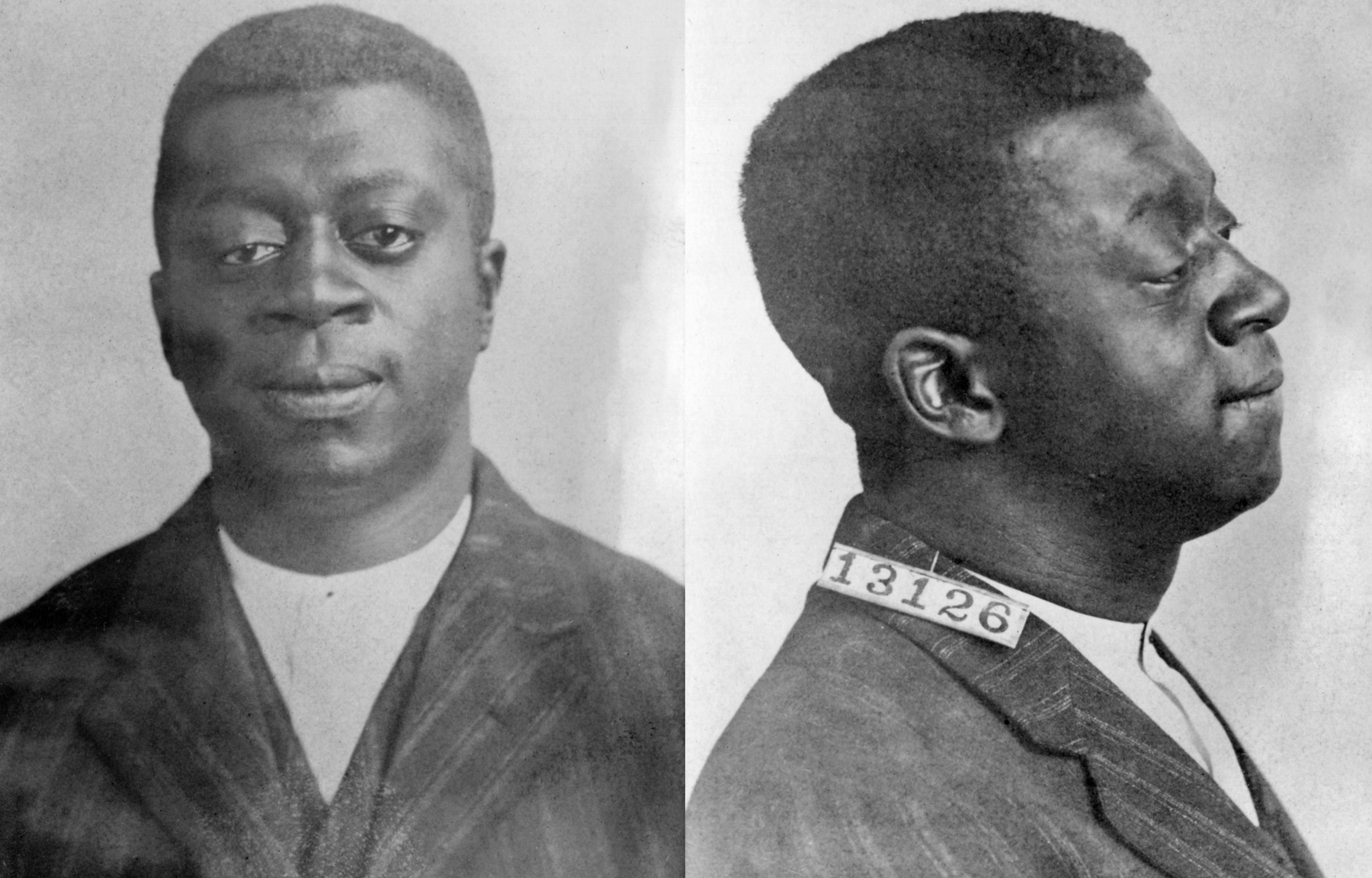

Ben Fletcher, militant labor leader

Ben Fletcher

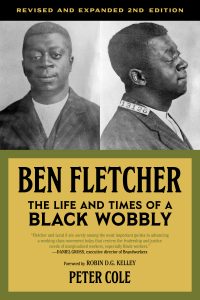

One of the greatest labor leaders of the tumultuous period of the early 20th century was a Black man from Philadelphia named Ben Fletcher. In the forward from the biography by Peter Cole, “Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly,” labor historian Robin D. G. Kelley describes Fletcher as a “radical pragmatist in that he paid attention to context, emphasized solidarity, and approached the work in an improvisatory and flexible manner — all without ever losing sight of the long-term goal: the emancipation of the working class from capital.”

Born in 1890, Fletcher grew up near the Delaware River docks where he eventually worked. Fletcher joined the Industrial Workers of the World around 1910 and became a leader of the new IWW Local 8 in 1913, steering the dockworkers local throughout the 1920s.

The local was born after a successful two-week strike by 4,000 dock workers. Local 8 was successful in abolishing unfair hiring practices and establishing a union hiring hall. Cole wrote, Local 8 “forced corporations in Philadelphia to deal with a union in which the great majority of members were African Americans and European immigrants. And they did it without ever signing a contract, instead enforcing their demands based upon the ever-present threat of a strike.”

Fletcher was a gifted public speaker. Letters about his speaking tour in the 1920s describe that at “several meetings about 1,500 have listened, spellbound . . .”; and Fletcher was the “only one I ever heard who cut right through to the bone of capitalist pretensions to being an everlasting ruling class, with a concrete constructive working-class union argument.” (Labor Notes, Dec. 17, 2020)

As Fletcher wrote, “While I do not countenance against the working class striking at the ballot box, I am firmly convinced that foremost and historical mission of labor is to organize as a class, industrially.” He advocated for a multiracial union movement, arguing: “No genuine attempt by Organized Labor to wrest any worthwhile and lasting concessions from the Employing Class can succeed as long as Organized Labor for the most part is indifferent and in opposition to the fate of Negro Labor.” (Labor Notes, Dec. 17, 2020)

Fletcher was a target of U.S. state repression of the IWW during World War I; the government labeled the IWW “a vicious, treasonable and criminal conspiracy” and tried to crush it. Many Wobblies were arrested. Fletcher, the only Black defendant, served several years in prison, after which he returned to Philadelphia to continue organizing with Local 8. (Labor Notes, Dec. 17, 2020)

Local 8 was one-third African Americans, one-third Irish and Irish Americans and one-third other European immigrants. Fletcher built the local in accordance with IWW’s commitment to interracial unionism, explaining that bosses benefitted by keeping Black and white workers fighting each other.

When the bosses hired nonmembers or fired any Wobblies, workers quit working. The IWW became a force to be reckoned with on the docks, raising wages and improving working conditions and putting an end to segregated work gangs. All union committees and activities were racially integrated.

Unfortunately Fletcher’s labor activism was cut short by a stroke in 1933; he died in 1949. Ben Fletcher left behind a powerful legacy of militant, anti-racist unionism.

Peter Coleis a professor of history at Western Illinois University in Macomb and a research associate in the Society, Work and Development Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Cole is the author of the award-winning Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area and Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia. He coedited Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW. He is the founder and codirector of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project.