By Keshler Thibert

Hidden City

May 16th, 2024

The new Ben Fletcher mural at 301 S. Columbus Boulevard will be dedicated on Saturday, May 18. | Rendering courtesy of Mural Arts

On Saturday, May 18, a dedication and celebration of a new mural honoring Black labor leader Ben Fletcher will take place on the Delaware River waterfront. The public artwork is the culmination of a collaborative effort between Mural Arts, the Philadelphia branch of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and the Racial Justice Committee of Philadelphia Democratic Socialists of America (PDSA). The mural will draw attention to a period of local history that often gets lost among communism, the Red Summer, the Negro Renaissance, the Great Migration, and World War I. It will also highlight the 111-year anniversary of a strike that resulted in a better work environment for Philadelphia’s dock workers.

Working Man

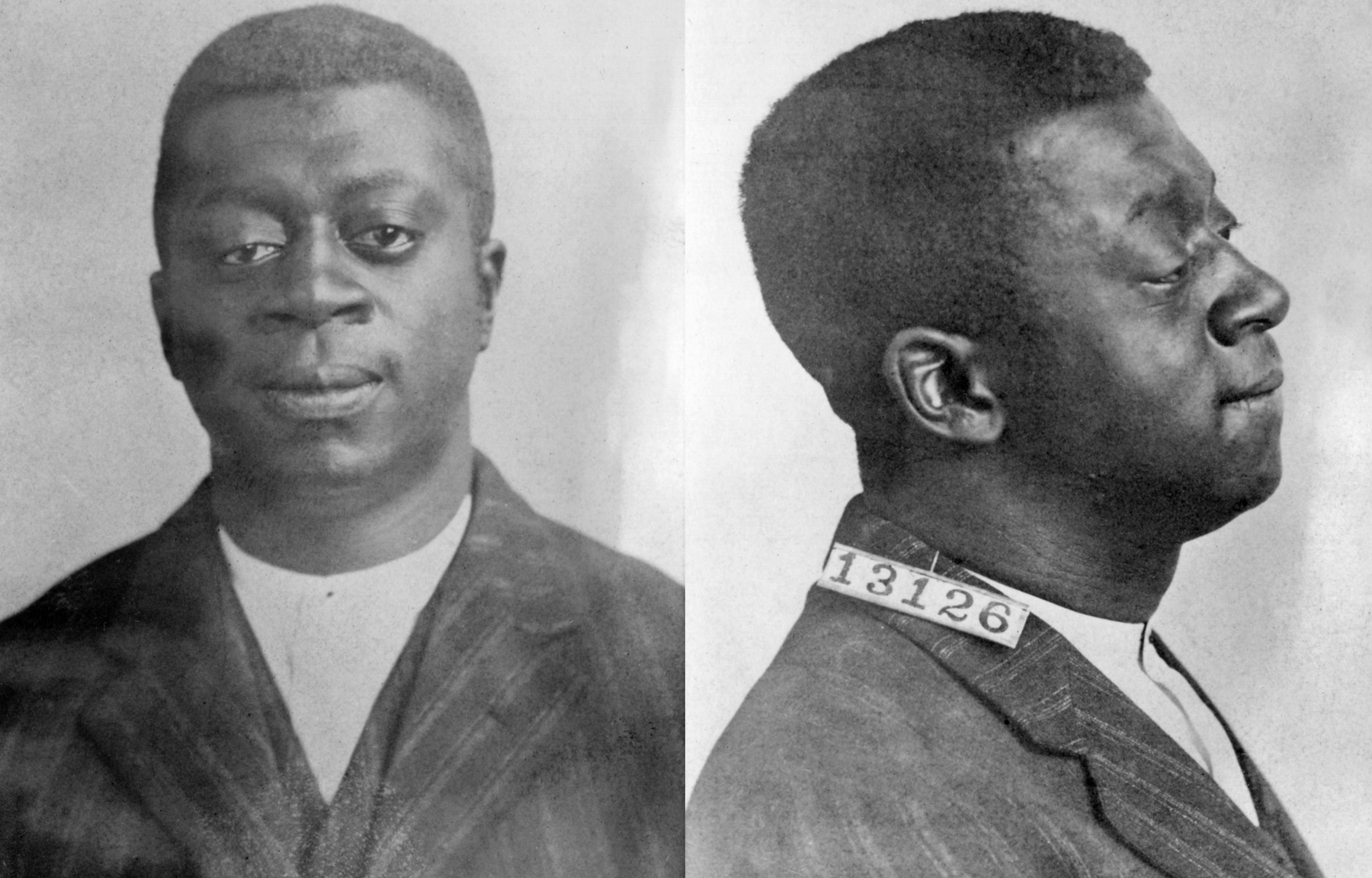

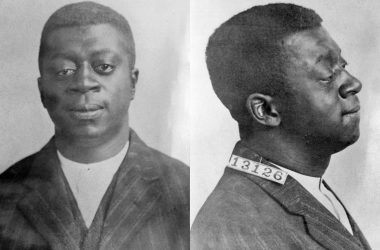

Fletcher, former head of Local 8, will be immortalized with the same smug look that has come to define his story. Local artist Jonathan Pinkett drew inspiration from a negative of Fletcher’s infamous mugshot he found on eBay. “It was the period of time when he decided to organize unions. He had to work his ass off,” Pinkett said.

Fletcher’s little-known history is about a relatable character. He was a Black child born in 1890 to parents who arrived in Philadelphia as part of the First Great Migration. Not much is known about his upbringing and his family. The 1910 census recorded him as a 20-year-old living in shared accommodations in the Point Breeze section of South Philadelphia. His profession is listed as a laborer most likely working on one of the piers along the Schuylkill or Delaware Rivers. Historian’s believe that his affiliation with unions began around this time. During this period, African Americans and other racial and ethnic groups were relegated to certain jobs from which they could not move upwards. Low pay and long hours were two of the realities Fletcher endured with his co-workers. These conditions prepared them for finding solutions to improve their situations through unionization.

This mugshot of Philadelphia union activist Ben Fletcher was taken in 1917. | Photo: Public Domain

Philadelphia’s Local 8 was founded in 1913. It is part of the Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union of the IWW, alternatively known as the Wobblies. Fletcher and his fellow founding union members had no other alternatives but to use radical tactics and sabotage as ways of slowing down productivity or striking to have their voices heard.

On May 14, 1913, Fletcher, along with 4,000 other dock workers, staged a 14-day strike that halted domestic and international trade. The act positioned the police and the owners of shipping and stevedoring companies against an organized working-class force composed of 52 percent Black, 39 percent Polish and Lithuanian, and 9 percent Irish and Italian workers. Until the 1920s, this strike was remembered with a day-long festival where dock workers gathered to celebrate their victory with a day off and a parade along the waterfront.

Soapbox

A report by FBI Agent Henry M. Bowen made on July 4, 1917 described Fletcher as a southern agitator with no real education and a “bad gunfighter” despite him never brandishing a weapon. Despite his lack of education, Fletcher was still able to lead the union around his belief that workers’ power could usher in a new society and that would require obliterating the color line, building a durable solidarity, and attending to working people’s immediate needs. His voice, sense of humor, and refusal to compromise drew people to him as he bellowed out from his soapbox to fellow dockworkers.

Fletcher’s efforts changed after the entry of the United States into World War I in April 1917. Despite asking fellow union members to work diligently as a show of support to the Allies, the Wobblies were labeled as criminals due to their critical views of the United States, specifically their views on war. The Espionage Act of 1917 turned members of the IWW and various chapters into “anti-patriots” who could face jail time, loss of employment, and possibly death by the police due to the unionists’ communist sympathies. Increased fears based on xenophobia and the dreaded Red Scare fed off the hysteria during a time when workers were needed to ramp up production.

Benjamin Harrison Fletcher poses with a young Benjamin Fletcher Homer in the 1940s. A friend named his son in honor of the labor leader. | Image courtesy of the Industrial Workers of the World

By September of 1917, Local 8 and IWW halls in Philadelphia were raided by the FBI and local police. Similar raids were also happening in other IWW offices throughout the country, leading to a slow dissolution of the unions by the U.S. government as it punished leaders with extended jail times and high fines.

Fletcher served 10 years in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary and was fined up to $30,000, effectively breaking the Local 8, but not Fletcher. He continued to organize and give speeches until suffering a stroke in 1933. He lived the remainder of his life in Brooklyn, New York. Fletcher passed away in 1949, and his remains were interred in an unmarked grave.

Path to a Mural

In 2022, I was lucky to be connected with Peter Cole, professor of history at Western Illinois University and author of the book, Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly. During that time, work on creating a public artwork with Mural Arts was already underway. The IWW, Philly DSA: Racial Justice Committee, and Cole received funding and approval, but progress was delayed due to COVID-19.

Why should such an obscure character be immortalized? According to Cole, “Fletcher was one of the country’s greatest Black radicals ever, and today a great many people are increasingly interested and hungry for inspirational, educational histories of such folks.”

Painter Jonathan Pinkett, at center, and attendees of the Ben Fletcher Community Paint Day at Cherry Street Pier in March. | Photo: Keshler Thibert

Matthew Atwell, a member of PDSA, shared his elation at the completion of the mural during a Ben Fletcher Community Paint Day in March 2024. Atwell has been a part of this project since 2021 when he learned about Fletcher and Cole’s book via a class on racial capitalism.

Along with the mural, the installation of a Pennsylvania state historical marker at the same site is in the works.

The Ben Fletcher mural will be officially dedicated on Saturday, May, 18 from 2:00 pm – 4:00 pm at 301 S. Columbus Boulevard. The celebration will include classic Wobbly songs, food, and stories about Fletcher and Local 8 history. The event is free and open to the public. RSVP here: https://www.phillydsa.org/ben_fletcher_mural