By George Lakey

Waging NonViolence

October 16th, 2012

Many activists have access to anti-oppression trainings, and that’s one place to learn the kind of “inclusive strategizing” needed to build movements that cross class lines. But beware! Some traditional training styles that activists use have been influenced unwittingly by classist assumptions.

I need to eat my own humble pie. I was part of the early anti-oppression training movement of the ’60s and ’70s, when we focused mostly on racism and sexism. Most of us came out of a protest background, so we had our share of outrage. We saw the workshop as one more opportunity to confront oppression fiercely, this time in the role of trainers rather than protesters. I remember moments of satisfaction after I’d “let them have it,” with little awareness of what the inner experience was of the workshop participants themselves.

Thank goodness that there has been some change since then, with more workshop space given for participants to breathe. There’s less shame-and-blame. Trainers no longer have such faith that they can guilt participants into correct behavior. More of the tools of popular education are now used, although some trainers who use participatory activities are still eager at the end to tell the participants what they were supposed to have learned, rather than assessing what they actually did.

I meet plenty of activists who say they will never willingly attend an anti-oppression workshop again because they don’t want to spend hours being told how bad they are. This, they know intuitively, is not empowerment. In activist circles where political correctness is still the norm, participants learn in workshops the language tricks to avoid being cast out of the group. (Definitions, for example: “Racism is prejudice plus power.”) Learning this year’s set of words gives a new activist a sense of belonging to the hip people. The trouble is, that kind of training invites people to walk on eggshells lest they say something that will get them “called out,” a humiliation to avoid.

Barbara Smith and I started Training for Change in 1991 to give activist education an energetic boost. She was an African-American working class organizer who was the first to lead a peace organization in Pennsylvania, and she had a previous career in education. I’d graduated from Cheyney State Teachers College, had a life-long fascination with how people learn in an empowering way and picked up a lot of facilitation lore from the civil rights movement.

Barbara and I both wanted to find a way to integrate anti-oppression work into our all-round pedagogical approach, rather than keep it apart as a separate topic. We were also both influenced by humanistic psychology, which reflects Aldous Huxley’s view that “rolling in the mud is not the best way of getting clean.” That forced us to innovate. A decade later the Aspen Institute studied our work as part of its national review of anti-racism training and found that we’d evolved a new and highly effective model.

Who calls out whom?

Once, a small liberal arts college asked me to spend a couple of days on campus and work with the group of students learning to be anti-racist allies. I asked them to share a moment in their lives when they’d experienced a new “ah-ha” about their own racism or another oppressive behavior. We made a long list. Most of the experiences were a variation on dialogue that included affirmation of the person whose behavior was being challenged. Only one person reported that being “called out” made the difference.

They trusted me enough to explore thoughtfully what was going on, since the reigning assumption among them deemed “calling out” the premier anti-racist tool — directly contradictory to their experience. Then someone named a pattern at that college: Seniors call out juniors, who call out sophomores, who call out first-years.

In more than one sense, classism! They learned from their activist culture that a tool that reinforces the class structure is to be preferred, even if it belies their own experience of what works. These students’ insight offers a breakthrough, because it stands for what is wrong with most traditional anti-oppression training: The focus is on managing and correcting and teaching — in other words, the hallmark function of the middle class.

Working class people who haven’t been to college rarely confront each other by calling each other out. They banter, they joke, they express anger in that egalitarian style that implies they’re ready for an argument. Generally, they don’t correct, because they don’t like bosses and don’t want to be one.

Middle class people, however, are trained to respect bossing and bossiness, so the result is a version of anti-oppression work that reinforces class roles. That version doesn’t question the effectiveness of “calling out”; it comes from being socialized to play the economic role of the middle class: managing, correcting, sorting people into acceptable and unacceptable.

No one will ever know how many people have shut down and left activist groups because — whether they were brought up working class or not — they didn’t experience humiliation as consistent with respect.

The alternative to political correctness is liberation

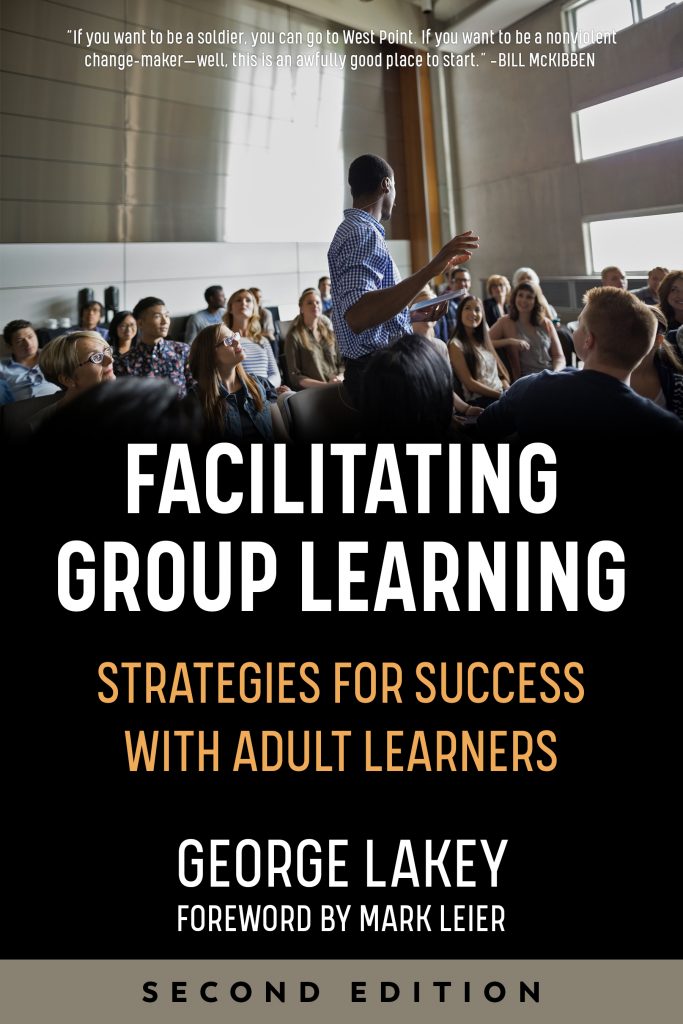

An alternative to “calling out” and other classist practices embedded in traditional trainings is offered in my book Facilitating Group Learning. The good news is that we can replace “anti-oppression” with “liberation” workshops that empower all people to take on the 1 percent, whether those people’s backgrounds are owning, middle or working class. Examples of what the training activities look like can be found in my earlier columns.

Here’s another example. Nationally-known working class activist and trainer Linda Stout taught us at Training for Change the “class line,” which we found more powerful than the common “class step-forward/step-backward” activity. In the class line, the workshop participants distribute themselves along a spectrum according to their family’s economic circumstances when they were 10 or 11 years old. They do that by talking with each other and puzzling out class indicators and rearranging their place in line and continuing to do that as fresh insights occur. For most people, it is the first time they’ve related to class in a personal rather than abstract or moralistic way.

The line then forms into small affinity groups, in which participants talk more about their backgrounds and try to recall what messages they got from parents and others about “their kind of people,” and also what messages they got about “those other kinds of people” at that age. Participants inspire each other to recall poignant memories they didn’t know they had, full of meaning for class prejudice, internalized oppression, and how people recognize or stay unaware of class struggle.

The facilitator in this kind of “direct education” is not an advocate of political correctness but helps each participant reach a new level of honesty and understanding — whatever level is available at that moment.

Direct education is conflict-friendly, so facilitators support arguments and emotional expression when the group is strong enough to handle them. The biggest working class gift to education is the value of direct conflict in the learning process, because conflict can be one of the surest routes to empowerment for all who are engaged in it.

What could inclusive training mean for activists?

The effect of this kind of training could do a lot to change how people organize. For one thing, activist groups would become more diverse internally — not only class-diverse, but also more inclusive of racial and other differences — the better to make coalitions that can outnumber and outflank the 1 percent. The Tea Party phenomenon, in which some working class people are misled into alliance with the 1 percent, could be reduced in numbers and power. A peek into what’s possible was given in my column on the alliance between international solidarity activists and longshoremen. Activist groups would have more grit and more vision, more endurance and more resources, more acceptance of individuality and the experience of more community. We would win more campaigns, park our despair and strategize for a living revolution.

So, what is holding us back? Not enough people are humble enough to accept the need for training. Class Action, Training for Change and other organizations are experienced in offering both consulting and training to activist groups that yearn to be more effective. The opportunity exists, for all who want to break out of their bubble and win.

George Lakey has been active in direct action campaigns for over six decades. Recently retired from Swarthmore College, he was first arrested in the civil rights movement and most recently in the climate justice movement. He has facilitated 1,500 workshops on five continents and led activist projects on local, national and international levels. His 10 books and many articles reflect his social research into change on community and societal levels. His newest books are “Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians got it right and how we can, too” (2016) and “How We Win: A Guide to Nonviolent Direct Action Campaigning” (2018.)