By Michelle Cruz Gonzales

Razorcake

September 8th, 2020

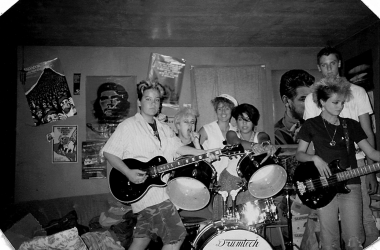

1984: Past, Present, Future

In

1984, the actual 1984, I saw the band Reagan Youth at the Democratic

Convention held that year in San Francisco with my friend, and

soon-to-be bandmate, Nicole Lopez. I was fourteen, clad in black and

flannel, with freshly chopped hair. Nicole’s mom drove us three hours

from our small town in the California foothills to San Francisco just so

we could see the bands and take part in the protest. A protest site was

designated in the empty lot at Mission and Howard across from the

Moscone Center, which back then (pre-multi-million dollar buildings on

every square foot of empty space) was simply a large slab of concrete

that took up the entire city block. It was there amongst a sea of

leather jackets, mohawks, ripped jeans, and undercover cops cleverly

disguised in jean jackets and protest buttons that Reagan Youth played

with the Dead Kennedys, MDC, and the Dicks.

Given the

ominousness of the year 1984 and the draconian policies put in place by

the outgoing president whose policies had further marginalized the lives

of many (especially youth from low-income families) there was a lot to

protest. Sort of unknown on the West Coast, Reagan Youth played early in

the day, drew an enthusiastic crowd of white, brown, and black punk

kids with their energy and aptness of a band with their name playing the

Rock Against Reagan tour. Dave Insurgent, who for some reason had

hippie-punk, white-boy dreadlocks, stood at the edge of the stage,

leaned into the crowd and incited our ire. Frustrated about class

hierarchies, Reagan Youth drew the lyrics for the song “Brave New World”

straight from the book of the same name by Aldous Huxley. Many English

punk bands wrote anti-Thatcher songs during the same time period, songs

that also referenced dystopian texts, or the dystopian nature of the

Reagan/Thatcher era that was punctuated with military escalation and

pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps style welfare reform.

Growing up Xicana in a small, predominately white town in California, I

felt much like a dystopian protagonist: trapped in a world that denied

me my individuality. A spiky-haired, black eye-liner, ruffled Mexican

rick-rack-skirt-wearing teen, I noticed many punk kids came from broken

homes, had parents who were addicts, or lived in boring go-nowhere

suburbs. We hated polo shirts and boat shoes. We hated high school,

sports, and anything else that felt like a popularity contest or that

only served to distract us from the fact that we faced a very uncertain

future amid the Cold War and threats of nuclear destruction. We were

depressed. Our lives, as we were living them, didn’t fit. While many

adults tried to make us feel like it was us, like we weren’t right, like

we were messed up, like we were the problem, we had enough sense to

know there was more to our dissatisfaction, our anger about social

control and feelings of alienation. Angry punk rock songs and angsty

literature were good outlets for these feelings. The Subhumans song “Big

Brother” is a perfect illustration: “Here we are in the new age/There’s

a scanner in the toilet/To watch you take a bath/And there’s a picture

of Hiroshima/To make sure you never laugh.”

In my teen years, it

was political punk rock that helped me cope with feelings of

estrangement, traumatophobia, and dying of radiation poisoning. When

punk rock wasn’t enough, I turned to dystopian fiction, a literary genre

seemingly designed for punk rockers and teens who drew mushroom clouds

on their binders. Dark in tone and topic, dystopian literature

definitely wears all black.

Like punk rock, dystopian

literature is urban, gritty, and grayscale, and like many punk rock

bands, dystopian literature makes important critiques of society.

Dystopian literature sneers satirically at inequality, hierarchical

divisions, and autocratic rulers—punk rock often does the same. And

probably for these reasons, many punk bands reference dystopian novels

in their songs. Like Subhumans, Dead Kennedys reference 1984 in

their song “California Über Alles,” an anti-Governor Jerry Brown song, a

song that shouts down yuppies taking over the state and making kids

meditate in school: “Close your eyes, can’t happen here/Big Bro on a

white horse is near.”

The majority of the Dead Kennedys lyrics

are satirical, and satire is a device/genre that makes extra close

examination of meaning especially important. Unlike what many of my

students often initially think, author Jonathan Swift is not being

literal when he proposes we turn to cannibalism and eat babies to help

the poor. And satire is partially responsible for my early confusion

about the song “California Über Alles.” Even at the age of fifteen when I

blasted it in my room and pumped my fist in the air, or when I saw the

Dead Kennedys at the Mabuhay Gardens in San Francisco, I’d wonder why

pick on a liberal Democrat? Why pick on Jerry Brown? Looking at these

lyrics now, I, of course, realize why. First off, 1984 author

George Orwell would say all people in power should be questioned and

scrutinized. Secondly, if you look closely at what Jello Biafra, singer

and lyricist of the Dead Kennedys was critiquing, you see yuppies. Look

again at all the lyrics, and you’ll see gentrification in the song’s

references to jogging, organic food, and “zen fascists.” Biafra’s fears

of a “cool, hip” (read expensive) California have come true, especially

in the hyper-gentrified, and now exclusive, San Francisco where the Dead

Kennedys were based. Go see it for yourself if you can afford the trek.

Take a hard look at tent cities, where people priced out of apartments

now live, all that they own in the world lining freeway off-ramps, set

amongst a backdrop of towering glass buildings and ten-dollar tacos.

Political punk rock has always been an urgent critique of immediate

concerns, a sort of real-time social critique in song, while dystopian

novels are cautionary tales. Yet, the themes addressed by the two are

often the same: squashed individuality under the pressure of societal

norms, corporate control of our lives, and subtle and overt forms of

propaganda used by democratic nations that should know better. The band,

Set It Straight from Redding, Calif. (active 2004 -2007) addresses some

of these themes in the song “Self-Deprogramming.” It was written prior

to Gary Shtenyngart’s modern dystopia, Super Sad True Love Story,

a novel about the dangers of group think and a nation obsessed with

mobile devices, youth, and hotness ratings. The novel, published in

2010, and the song have a lot in common, “Super latte charged electrons,

androids with no face/ But only those who subconsciously want to live

their lives spoon fed/ subordinated, placid, incarcerated, succumb to

the machine.” Like Shytngart’s Super Sad True Love Story, this

song criticizes modern-day forms of brainwashing via slick technology

and the allure of power. Its references to lattes and androids are

familiar dystopian fears regarding loss of individuality and a loss of

humanity. It’s a loss of humanity we sadly participate in via our

robotic obsession with digital technology that often does the thinking

for us.

Robots, surveillance via mobile devices, and other futuristic dystopias, almost seem quaint compared to what is happening now.

A Dystopian Bait and Switch

Of course, robots, surveillance via mobile devices, and other futuristic dystopias, almost seem quaint compared to what is happening now. In the post-smart phone 2000s, while we were busy worrying about digital technology spying on us, replacing humans, and stealing our jobs, what many thought were archaic forms of xenophobia, misogyny, and gender terrorism roiled hot and ready to explode, and an old-school totalitarian was making his move. Now trapped in a dystopian landscape of our own, Donald Trump used his celebrity, wealth, and privilege to invoke ages-old rapist-terrorist-nativist-racist fear mongering and won the election and the culture wars with help from the outdated and systematically racist electoral college. As president of the United States, he continues to animate mobilize a surprisingly large base of people and sow unnatural distrust of the media. He has also attempted to rewrite history as it happens and our perception of it—a major feature of Orwell’s totalitarian regime in 1984.

What many thought were archaic forms of xenophobia, misogyny, and gender terrorism roiled hot and ready to explode. An old-school totalitarian was making his move.

Some unclear about the purpose of the genre believe dystopian novels have, in some ways, foretold the future, but dystopian novels, like many punk songs, are really meant to be critiques of folly in our current societies. Still, one person’s dystopia is another’s utopia. For those swayed by promises of walls, Muslim bans, mass deportations, and nativists’ vision of America (not to a mention a threat of a reversal of a woman’s right to choose and transgender rights) we have entered what the party leader, O’Brien, in 1984 called the golden country: a place where everything seems fine, everyone looks like you, acts like you, believes what you believe, a place where no one is a threat or a challenge to the status quo and where those who disagree are silenced. But we are not fine. So many of us have become reacquainted with our inner angsty teenager or our inner dystopian protagonist. We will re-read 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale, Herland, We, Parable of the Sower, and we will pump our fists in the air to our favorite punk songs, but that’s not all we’ll do. No, that is not all.

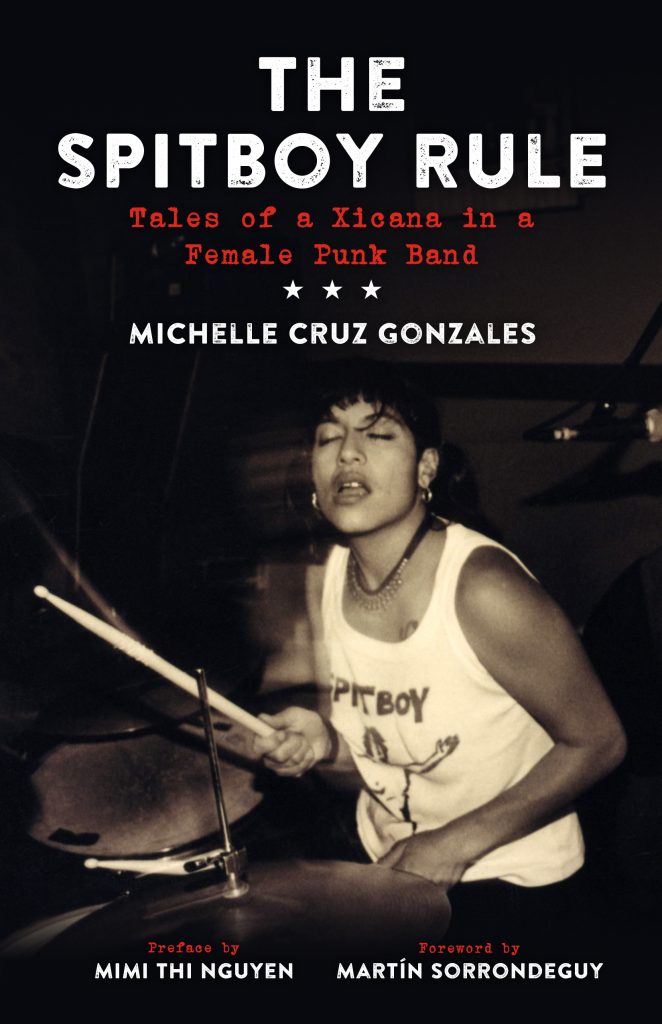

Michelle Cruz Gonzales played drums and wrote lyrics for three bands during the 1980s and 1990s: Bitch Fight, Spitboy, and Instant Girl. Her writing has been published in anthologies, literary journals, and Hip Mama magazine. Michelle teaches English and creative writing at Las Positas College, and lives with her husband, son, and their three Mexican dogs in Oakland, California.