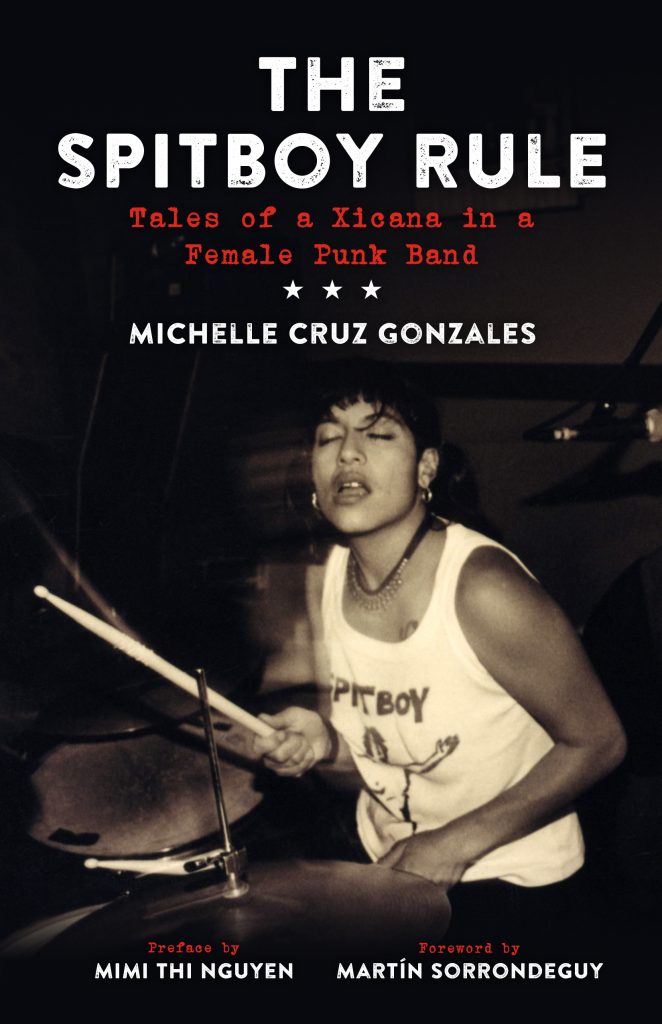

By Michelle Cruz Gonzales

Razorcake

July 20th, 2021

The ice age is coming, the sun is zooming in

Meltdown expected, the wheat is growin’ thin

Engines stop running, but I have no fear

’Cause London is drowning, and I, I live by the river

–The Clash

At the age of fourteen, I learned just about everything I needed to know about the future of my life on earth from the song “London Calling” by The Clash. Like “London Calling” and its apocalyptic message about war, global warming, food shortages, and floods, a lot of punk songs have a way of making you face reality. And “London Calling” and songs like it, gave me an angry anthem and solid reasons to distrust progress and people with power. Growing up in the ’80s, the threat of nuclear war weighed heavy on teenagers just starting their lives. For many years, the only future I could envision is one with a mushroom cloud in it—of course a lot has been written about the relationship between these fears and the nihilism in punk. Between growing up in a small-minded, go-no-where place and the very real possibility of nuclear war, I had little sense of what people referred to as the American Dream, or any kind of clear hope for the future. I knew that I wanted to play music and to move to the Bay Area with my first band Bitch Fight, because at least that would make me happy.

Growing up in the shadow of the Vietnam War and in the midst of the nuclear arms race, us Bitch Fight girls became vehemently anti-war. One of the best anti-war punk songs can be heard on a 7” Peace? by The Dicks.“No Fucking War” is a classic anti-war song in the vein of “War (What Is It Good For?)” performed by Edwin Starr, and Gary Floyd seems to conjure Starr with his own vocal performance. But The Dick’s song did something new. It connected war to the American Dream, correlating America’s relentless war addiction and the way winning wars—or claiming to, even when thousands die—feeds the American Dream.

Well, here we go again

Another war to win

It’s the American Dream

Can you hear us scream

We don’t want no fucking war

We don’t want to fight no more.

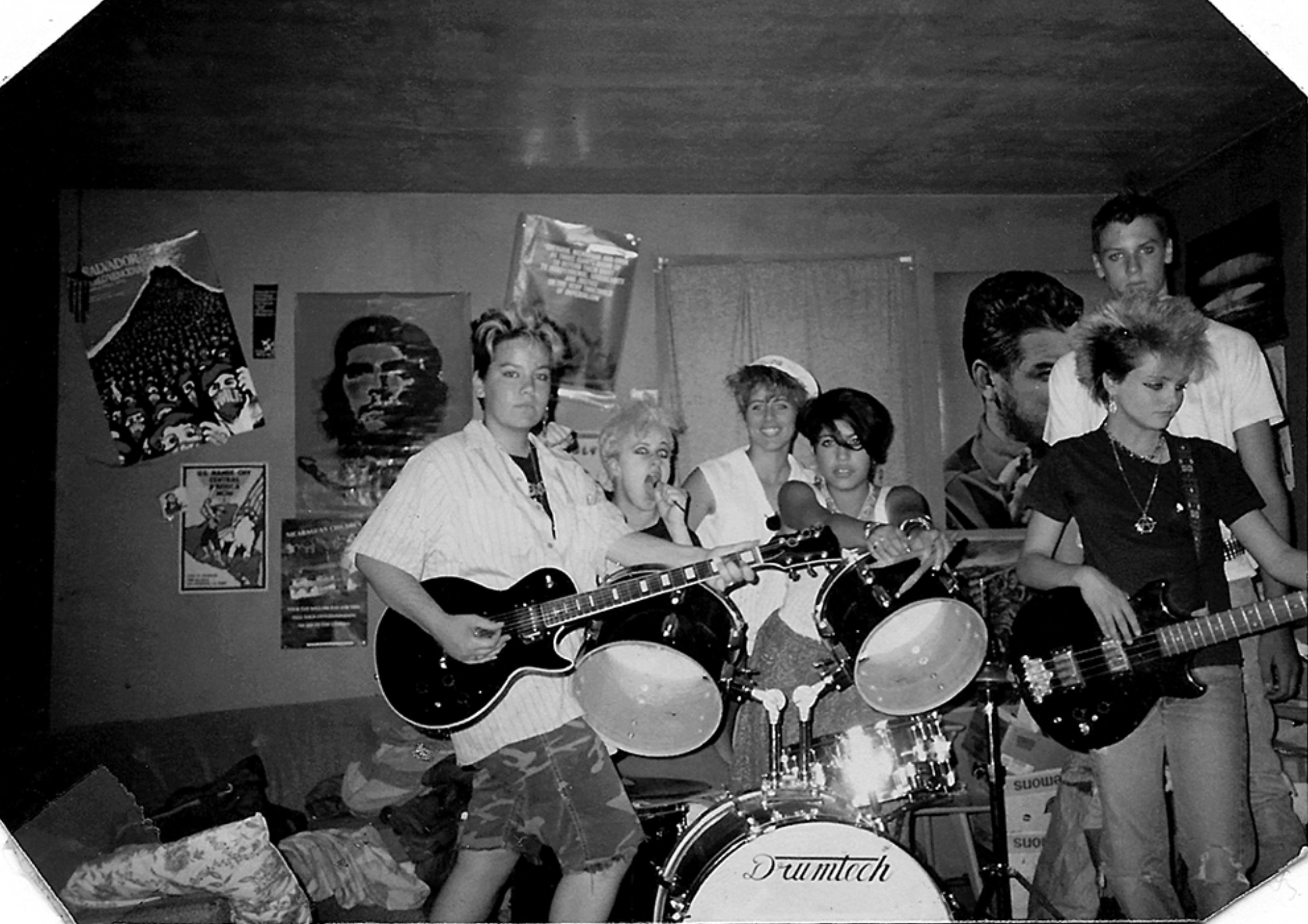

When I saw The Dicks play, I gripped the stage with one hand, pumped my fist in the air with the other, and screamed along with their towering and gorgeous woman drummer, Lynn Perko, who also sings on the song. I would soon after start playing drums and singing backup too. On the record, her voice soars over Gary Floyd’s lower register during the chorus which makes me smile every time I hear it. Not knowing that we were the very first punk band in Tuolumne—and all girl band at that—Bitch Fight wanted to make something of our band, play shows, and make records, but we also had a vague idea that we’d go to college. Only, we didn’t really know how to make that happen or if we’d survive four more years if it was going to look anything like high school. What with growing up in single-mom families with no money and a sense of a future eclipsed by megalomaniacs and war, Nicole Lopez, Suzy Carny, and I, founding members of the band and childhood friends, didn’t have the same kind of ambitions as young people our age with more privilege and more money, but we had punk. We had its honesty, its forthrightness.

At forty-six, when Trump was elected president of the U.S., another punk song played in my head, “White Man in Hammersmith Palais.”

All over people changing their votes

Along with their overcoats

If Adolf Hitler flew in today

They’d send a limousine anyway

Shawn Lopez (RIP), the Bitch Fight guitar player’s mom, was wicked smart and she loved The Clash as much as we did. She encouraged mine and Nicole’s interest in music, especially protest music. She was probably glad too when Nicole and I found each other and became friends in grade school, two Xicana band nerds who played the flute and had single moms. Shawn was a punk enabler, the kind of parent who tolerated, or even liked punk, drove their kids to shows, and helped them shave their heads. Another one of our friends, Josh, now an arson investigator, calls Shawn his commie mommie. It was Shawn who drove us ten hours to San Bernardino to see The Clash at the US Festival in 1983, from Tuolumne in her slow-ass Fiat wagon that she parked on hills so we could pop the clutch to get it started. We drove all night after school to get there and parked somewhere near the festival grounds by an empty field and slept in the car because we didn’t have money for a hotel, and because we wanted to be in line before the show started at noon.

And it was Shawn who explained the lyric from “White Man in Hammersmith Palais” about Hitler, how it’s about the dangers of a deference to leaders that compels us to roll out the red carpet, even for a genocidal murderer out of some twisted sense of decorum. The song rang in my head all day during the Trump inauguration, throughout the pomp and circumstance for a man who had referred to Mexicans as rapists and drug dealers, mocked the disabled, and bragged about sexually assaulting women.

My own mom likes punk now too, but she hates talk about Armageddon—scare tactics used by conservative Christianity to scare people straight. Punk, of course, doesn’t bother itself with Biblical rapture, but it does force us to consider that the end of the world could very well be a thing of our own making. Like when the Subhumans sing in “Dying World” about panic buying and fears of living in a world with a hole in the bottom

When you’re living in a dying world

Panicking becomes the everyday thing

Buy up the food, the power and the guns

Get used to the threat of the final fling

Punk has forced me to accept the fallacy of our comfortable way of life, the fallacy of safety, the fallacy of a government by the people for the people.

As I sit home, feeling lucky to have one and to be sheltered-in-place safe with people I love, I can’t help but wonder if this is our “final fling.” I don’t say this out loud because I live with hopeful young adults just starting out in the world. I laugh on cue when my eighteen-year-old son wanders through the living room and recites his new mantra in his best robot reporter voice, “Corona, Corona Virus, Covid, Covid-19.” I know it’s his way of coping with the fact that he, unlike his dad and me, has his whole life ahead of him possibly living under these conditions. I match his Covid chant with a song of my own, “It’s the end of the world and I know it, and I feel fine,” because while it is in my nature to comfort my family with meals made from scratch, old card games, and cozy hand-sewn pajamas, it is not in my nature to sugar-coat human folly. Punk has forced me to accept the fallacy of our comfortable way of life, the fallacy of safety, the fallacy of a government by the people for the people. Punk has, mostly, inoculated me from the kind of fear that I felt about the world as a teen and to stop believing lies just to cope. A combination of punk and my Xicanisma has divorced me from my American sense of rugged individualism, and made me believe that an actual bartering system that is not only made up of punk patches and zines is possible, a dozen of my flour tortillas for a dozen of my neighbor Cynthia’s chicken eggs, cooking at home as a demonstration of love for the community of people in my house, my children, who I won’t push out of the nest because they’re technically adults, dancing in the kitchen, and music and art that isn’t controlled and shaped by greed and consumer capitalism.

We don’t need stuff; we need each other.

We don’t need stuff; we need each other. We don’t need more and more space; we need to negotiate and share the space that we have. We don’t need bougie take out food; we need a recipe. We don’t need daily trips to the grocery store; we need to cook from the ingredients we have. We don’t need to work more; we need better pay. We don’t need Instagram-worthy vacations; we need more time in nature. We don’t need fast-fashion; we need to repurpose our clothes, shop in thrift stores, organize an exchange. We don’t need a 24-hour news cycle; we need the wisdom of stories, literature, punk songs, and talk around the dinner table.

I want to say all of these things to my son and niece but I know that actions are better, so I will continue to sing my favorite punk songs when I cook dinner, sew, or clean the house, and sing even if it’s too loud for being sheltered-in-place because I want them to learn to associate, familia, comunidad, and comida buena with the possibilities of an unvarnished but honest existence.