By Chad Pearson

H-Labor

June 2021

Reviewed by Chad Pearson (Collin College) Published on H-Labor (June, 2021) Commissioned by David Marquis (The College of William & Mary)

Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56652

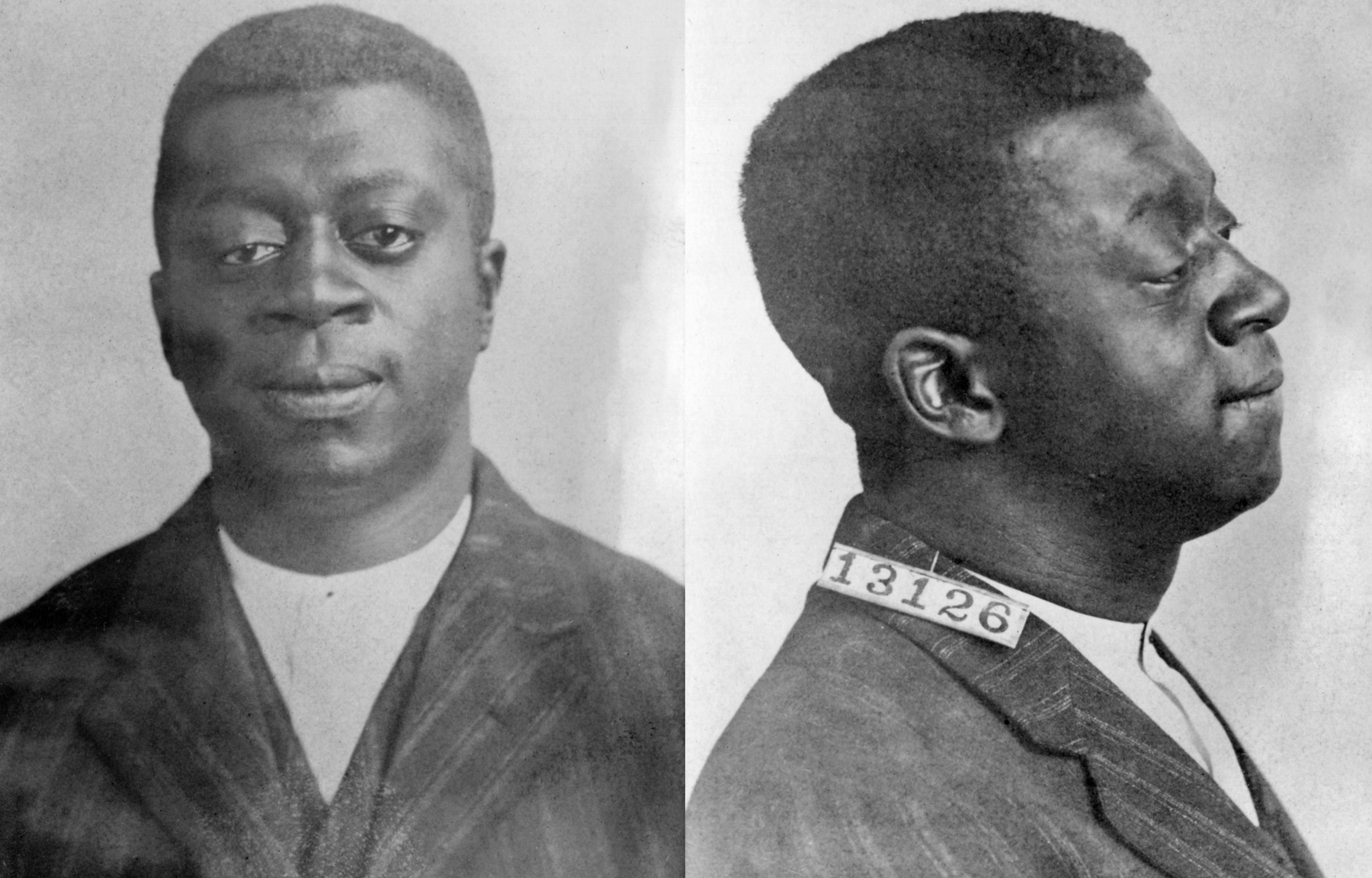

I have too often heard the following critiques: labor history is simply the study of white men in unions, and labor historians have done a poor job of exploring divisions and identities other than class. These claims ignore more than half a century of “new labor history” scholarship—loads of books and articles by Herbert Gutman, David Montgomery, Jacqueline Jones, Tera Hunter, Joe Trotter, and many others that examine the historical experiences of racially and ethnically diverse working men and women both in and outside of workplaces—that disproves these sorts of statements. Moreover, labor historians such as Theodore W. Allen, Noel Ignatiev, and David Roediger were more responsible for introducing and popularizing “whiteness studies” in the 1990s than any other group of scholars, and one does not need to look far to find the enduring significance of this historiographical intervention. Phrases like “white skin privilege” and “the wages of whiteness” are regularly made in seminar rooms as well as in activist circles. Yet perhaps this overemphasis of white laborers’ racism without properly addressing the ways employers have historically promoted white supremacy, combined with an underappreciation of class struggles across racial and gender lines has harmed the place of labor studies in the academy, leading to the near erasure of the subject in numerous higher educational institutions. Sadly, few know about the combative struggles of Black and interracial unions, and most have never heard of Ben Fletcher (1890-1949), the influential and militant African American longshoreman and proud Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) member.

Maybe that will change thanks to Peter Cole’s wonderful investigative work. Cole, the author of two important books about the intersections of class and race in the labor movement, has recently re-released this edited collection, Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly, which consists of numerous thought-provoking articles, letters, and speeches by and about this underexplored labor activist. First published in 2007, this fine collection includes a new foreword by leading historian Robin D. G. Kelley and a useful, 62-page introduction by Cole. Both place the underappreciated Black labor activist in his time, outlining Fletcher’s rich experiences as an organizer and agitator, someone committed to fighting capitalism and racism while embracing the IWW’s famous slogan: “An Injury to One is an Injury to All.” In his preface, Kelley informs us that “Fletcher understood that only workers’ power could usher in a new society, and that required obliterating the color line, building durable solidarity, but also attending to working people’s immediate needs” (p. x). By examining Fletcher’s life, we can gain helpful insights into questions about race and class struggles.

Cole’s introduction, divided into twenty-two sections, provides us with the key context, summarizing Fletcher’s conflict-ridden world. Historians with prior knowledge about African Americans in the labor movement, academic newbies, and activists seeking to find inspiration from history will find this section highly valuable. We discover that Fletcher, a steadfast organizer with Philadelphia’s Local 8 of the IWW’s Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union, prioritized class struggles above all else. Fletcher, who started laboring on Philadelphia’s docks in 1910, earned a reputation as a reliable fighter against dictatorial bosses, disreputable employers’ associations, and an increasingly repressive state. In May 1913, he took part in a 4,000-person strike consisting of roughly half African Americans; the others were Irish Americans and eastern European immigrants. During World War I, Fletcher, like numerous other labor radicals, found himself on the federal government’s radar. In February 1918 he was arrested and sentenced to serve ten years at the notorious prison in Leavenworth, Kansas, but was ultimately set free by President Warren Harding in October 1922. During his prison stay, he interacted with fellow leftists, including future US Communist Party leader Earl Browder. The IWW remained important throughout these years, since it, as Cole reminds us, championed direct actions against bosses and promoted class struggles across racial and ethnic lines, a sharp contrast from the American Federation of Labor’s (AFL) International Longshoremen’s Association, which organized African Americans in segregated locals. “Where it had the power,” Cole explains, “the IWW ended segregation—without a legal contact, without an electoral campaign, and with zero influence among local or national politicians” (p. 22).

Most of the book consists of newspaper articles and letters that Cole has meticulously collected: “Every known letter or essay written by Fletcher is included as is nearly every mention of Fletcher by someone else” (p. 61). Thankfully, Cole provides brief introductions before each entry. Writings about Fletcher are especially illuminating, and we learn that well-known figures recognized the significance of his activism. Cole introduces us to writings by trade unionist A. Philip Randolph, historian Abram Lincoln Harris, and leading intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois. Some observers marveled at the ways Local 8 promoted inclusivity and combativeness. In fact, Du Bois, someone who witnessed examples of bigoted union behavior during his life, praised Fletcher and the IWW for leading “one of the social and political movements in modern times that draws no color line” (p. 129).

While Du Bois insisted that racism benefited whites irrespective of their class position—famously coining the phrase “the psychological wages of whiteness”—Fletcher focused primarily on those at the top of society, singling-out the nation’s businessmen-exploiters. Fletcher identified how managers routinely profited from nefarious “divide and conquer” techniques, writing in 1923 that “it is needless to state that the employing class are the beneficiaries of these polices of Negro Labor exclusion and segregation” (p. 194). At the same time, Fletcher was fully aware of racism’s long reach and poisonous impacts, recognizing that far too many white workers, many of whom held membership in racially regressive AFL unions, identified with their race rather than their class.

While employers and members of the federal government mostly tolerated and sometimes encouraged racist white workers, they actively sought to undermine the IWW. The worst of the repression occurred during World War I, falsely labeled by Woodrow Wilson and his defenders as a war to make “the world safe for democracy.” IWW activists certainly did not experience democracy since many authorities systematically prevented them from freely speaking and assembling. Fletcher believed that he and his comrades faced the wrath of state and capital forces partially because of their progressive racial politics. Note his words from 1920: “It was held then that race prejudice must not and will not be permitted to play any part in the IWW.” For that reason, “the IWW is damned, persecuted and lied about by the employing class and their minions” (p. 153). Fletcher’s comments here are critical in challenging the liberal historians, sociologists, and essayists who have insisted that labor unionists, rather than employers, were the primary agents of spreading racism.

Fletcher experienced racism in both casual and near-deadly ways. Most dramatically, he was almost lynched in Norfolk during an organizing trip in 1917. He was ultimately saved by fellow IWW members who helped him escape by smuggling him “aboard a northbound ship to Boston” (p. 25). In addition to disapproving of his militant unionism, these threatening men opposed interracial relationships. It is noteworthy that Fletcher married a white woman in Boston.

Following World War I, Fletcher continued to confront obstacles. He viewed the establishment of the second Ku Klux Klan, for example, as part of a broad, employer-backed campaign to halt the working class’s march forward. Although the Klan enrolled members across class lines, Fletcher and his comrades understood that the organization served the ruling class’s interests. Of course, not all postwar business owners and managers were members of explicitly white supremacist organizations, but virtually all opposed the IWW. Many aggressively waived the US flag, declaring that the anti-union open-shop system of management was not only good for individual workers but was also fundamentally “American.”

Another group that harmed the efforts of Local 8 were the Black separatists involved in Marcus Garvey’s movement. Obviously, Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association was far less physically threatening than the Klan, but it did challenge promoters of class unity across racial lines. Cole includes writings from sympathetic observers of Fletcher’s labor activism at a time when race-based organizations were growing. Consider the words of Charles Owen and A. Philip Randolph, writer-activists who penned essays about the ways IWW members of all races and ethnicities rejected the Klan and the Garvey-led movement. Writing in 1921, they observed, “From the floor, white and colored workers rise, make themselves heard, make motions, argue questions pro and con, have their differences and settle them, despite Imperial Wizard Colonel William Joseph Simmons’ and Marcus Garvey’s ‘Race First’ bogey” (p. 169). In another essay, also published in 1921, Owen and Randolph recognized how these marine transport workers remained firm in their advocacy of biracial unionism: “It is interesting to note, in this connection, that the white workers were as violent as the Negroes in condemning this idea of segregation” (p. 161). These unionists went to great lengths to maintain picket lines and pressure their bosses: “It is a matter of common occurrence for Negro and white workers to combine against a white or a black scab” (p. 162).

One of the collection’s strengths is that it traces Fletcher’s political ideas and activities in the years after the dramatic post-World War I confrontations, when Fletcher mourned the decline of labor militancy and radicalism. Writing in 1929, he remarked, “Those of us in on the know know, that the AFL is committed to preserving the status quo between Capital and Labor, and to act as a bulwark against working class dictation to capital” (p. 224). But he voiced enthusiasm about the uptick in struggles in the 1930s. Although he was in poor health, he continued to champion workers’ movements in places like Kentucky, where Harlan County coal miners staged a series of disruptive actions. He shared the stage with progressive luminaries, including Roger Baldwin, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Norman Thomas.

Though suffering from hypertension, Fletcher continued to correspond with activists and researchers in his later years. He expressed disappointment with the state of the labor movement during World War II, a time when union leaders sold out rank-and-filers by signing no-strike pledges and backing the pro-capitalist Democratic Party. “The Union idea,” he wrote in 1944 to fellow IWW veteran George Carey, “doesn’t exist any more, in sufficient account to assume a challenge worthy of consideration by the powers that are” (p. 252). Such comments are especially useful in our present historiographical climate, one dominated by liberals guilty of romanticizing the state of organized labor during the 1940s. Fletcher knew better.

Historians and activists will find much value in these essays, speeches, and letters. Hopefully, the book will attract interest in scholarly communities, where labor history’s detractors will be forced to stop making misleading comments about the subject. Additionally, today’s activists can learn underexplored lessons about the power of multiracial unity. Black Lives Matter protesters have already discovered the necessity of building broad unity against our excessively repressive state. Books like this one will reinforce what many of us know: direct action—against bosses in workplaces and police in the streets—is a far better way to build working-class unity and advance demands than wasting time trying to reform the Democratic Party.

Citation: Chad Pearson. Review of Cole, Peter, Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly. H-Labor, H-Net Reviews. June, 2021. URL: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=56652 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

0 Replies

Peter Cole is a professor of history at Western Illinois University in Macomb and a research associate in the Society, Work and Development Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Cole is the author of the award-winning Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area and Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia. He coedited Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW. He is the founder and codirector of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project.