By David Rovics

May 24th, 2020

The City of Portland, Oregon, and Multnomah County, are doing the best job in the country at kicking the can down the road. Now is the time to push for a real solution to the housing crisis, here and across the USA.

Since the pandemic hit, I have joined the ranks of the unemployed, like

so many others have. Dozens of gigs planned in nine countries on three

continents canceled. I’m doing better than many of my fellow musicians,

because I have been moving more towards the modern, crowdfunded

patronage model of artistic existence for years now, in the wake of the

collapse of the music industry, which has never come close to recovering

from the transition from physical merch to “free.” I was expecting to

suddenly start losing my supporters on Patreon one by one, as my

supporters also were losing their own jobs, but so far that hasn’t

happened. Listening to interview after interview with other artists

from around Portland on local radio, though, it’s very hard times. As

anyone knows by now if they listen to NPR, many performing artists have

to do other things to pay the rent, which usually involves service

sector work of some kind, which of course disappeared along with their

gigs, when the cafes, bars, restaurants, convention centers, schools,

libraries and theaters all closed, and festivals were, of course,

canceled.

For the first time in my 53 years as a US citizen, I qualified for

unemployment insurance. For any of you better-off foreigners who aren’t

familiar with the dog-eat-dog barbarity that underlies the principles

on which most US states run their unemployment insurance programs: if

you didn’t pay into the program with a traditional kind of job involving

payroll and payroll taxes, you don’t qualify to benefit from it if you

find yourself jobless. So this leaves out increasing numbers of the

workforce, what we now call “gig economy” workers, such as, obviously,

touring musicians, but also so-called “contract workers” such as Uber

drivers and all kinds of other people who appear to be working for a

large corporation but are actually “self-employed,” through some kind of

capitalist magician’s sleight of hand. Maybe even an invisible hand,

now suddenly very visible, slick with the sticky blood of its multitude

of victims.

But, just in time to prevent who knows what from happening (I was

definitely smelling smoke), the Congress acted, and expanded

unemployment to include something closer to the actual number of

unemployed workers — not counting the estimated 11 million

undocumented, or the unpaid homemakers, and so many others, but still

much better than it had been before they passed the PUA (Pandemic

Unemployment Assistance). I applied for it, soon after it became

possible for people like me to do so. I received a confirmation from a

bot that my application was received, and that’s all I’ve heard from the

government since early April, aside from the one check signed by Donald

Trump himself, that did arrive, now a long time ago.

What we’re clearly seeing in terms of the overall national response to

the situation here in the US exposes the dire flaws within both the

anemic public health sector and within the capitalist economy, which, in

the US, is a kind of house of cards constructed on top of a ponzi

scheme called the real estate market. In other countries, it seems,

with highly functional governments, and economies that aren’t mainly

based on speculation on and investment in the real estate market, it’s

possible to temporarily freeze the economy — defer mortgages, cancel

rents, maintain industries and jobs with government support so they’re

all still there when the crisis is over, etc. But in the US, it seems

even the idea of deferring mortgages and canceling rent during the

crisis would cause the ponzi scheme to collapse, this whole industry

which is based on a constant stream of profits that far, far exceed any

actual rise in wages or spending power of the average person. Here in

Portland, rents typically go up close to 10% each year, which has

resulted in the ethnic cleansing of this city, which lost more than half

of its African-American population between the last two censuses, and

also lost most of its artists, and so many others. The city is

unrecognizable, compared to twenty years ago — like so many other

cities in the US, but worse. Portland is the most expensive city to

live in in the entire United States, when you consider the cost of

housing relative to the income of the average resident.

Although we aren’t seeing any systematic deferment of mortgages or

canceling of rents in the US, what we are seeing are lots of temporary

bans on evictions. It’s a confusing, patchwork affair, that will

probably see waves of evictions happening in some places long before

other places, depending on the initiatives of city, county and state

governments. Here in Portland, where the housing crisis was a crisis

before the pandemic crisis — possibly the worst-hit city in the United

States in terms of homeless residents, people living in cars or

extremely overcrowded apartments — there has also been the clearest

temporary ban on evictions of anywhere in the country.

What this means, to be clear, is the city of Portland — and Multnomah

County, which includes Portland and some Portland suburbs — has done

the best job of kicking the can down the road. The ordinance passed

almost definitely applies to anyone who used to make a living as an

artist of any kind, along with lots of others. If your income was

dramatically impacted by the pandemic and associated lockdown, you can

defer your rent payments until six months after the county has

determined that the crisis is over. At that point, you may owe your

landlord tens of thousands of dollars, all of a sudden, and thus, the

main waves of evictions will happen then, rather than this summer, where it will happen in many other places.

There is a lot of chatter on social media. I say this not to denigrate

the chatterers, but to denigrate the platforms on which they are

chattering. Not that we can avoid these platforms, but Facebook and

YouTube feed on conflict and feed us conflict. So whatever chatter is

going on on such platforms is best either ignored, or understood in that

context.

There’s also some real organizing going on, with tenants unions

in Los Angeles, New York and elsewhere really talking to their neighbors

and systematically withholding rent in order to get real demands met.

Nothing on that scale is happening yet here in the most heavily

rent-burdened city in the country, and at least one of the main efforts

on social media taking place currently seems to be led by someone

motivated primarily by a personal grudge against one of the most

effective rent control advocates in the city — perfect for Facebook,

where this sad excuse for organizing seems mainly to be taking place,

where such grudges can be exploited by Zuckerberg’s favorite conflict

algorithms.

But real rent strike organizing here in Portland is very desperately

called for right now. And I don’t say this just because I’m an

anarchist who is generally in favor of rent strikes, although I am most

definitely guilty of both charges. A rent strike is called for in

Portland not only because many people are currently unable to pay

their rents, although that itself would be plenty of reason for one. A

rent strike is called for now in particular specifically because we have the best chance of winning such a struggle right now, because we have one of the most progressive local city and county governments in the country right now.

If this seems contradictory, it shouldn’t. The most widespread labor

organizing in the United States over the past two centuries of the labor

movement did not just take place during a period of extreme inequality

and exploitation of workers. Inequality and exploitation was absolutely

massive across the US throughout the nineteenth century and early

twentieth century. Radical labor unionism was at its peak with the

Industrial Workers of the World in the early twentieth century. Yet the

lion’s share of unions that were successfully organized were organized

when there was not only massive inequality, during the Great Depression

of the 1930’s, but also during a period when there was a sympathetic

government that had been elected to power — the administration of

Franklin Delano Roosevelt. For all Roosevelt’s many flaws, his

administration included a whole lot of bona fide socialists, from

top to bottom. When workers went on strike after 1932 things were not

easy, by any means, but they did not face the same kind of opposition

from federal authorities that they faced on so many key moments in the

history of the labor movement prior to 1932, and success after success in labor organizing is what followed.

Now here we are again, in a new depression, and with fairly sympathetic

city and county governments here and elsewhere, depending on where. If

we want to stop the wave of evictions that will come, we must now start

organizing against them. We have to stop the evictions before they

start. Some of the biggest and most successful unions during the 1930’s

were both formal and informal in nature, both organized by familiar

structures with presidents and treasurers and such, and also organized

through the widespread idea that this world did not belong exclusively

to those who could afford it. Ideas that were spread on the street,

through means of guerrilla theater, songs, posters, newspapers, and

through a myriad of other platforms, became commonplace. Chief among

them: that humans have rights. Rights not only to free speech and

assembly — which millions of people were exercising daily — but rights

never mentioned in the much-vaunted foundational document of the

nation: the right to sufficient food, and the right to housing.

When police and landlords attempted to evict tenants during the

Depression, oftentimes gatherings of organized unemployed people would

prevent the evictions from taking place at all. Other times, the

eviction would happen, but then an unemployed locksmith would come and

change the lock, and other unemployed workers would carry the tenant’s

belongings back into their apartment, thus un-evicting them. There were

many successful rent strikes during this period, as well as at other

times and places in history. They resulted in buildings being bought by

occupants, or given to occupants with government intervention or

government loans (as just happened last week in Minneapolis), or by

rents being lowered drastically, or by new rent control laws of all

kinds being passed, giving tenants rights they never had before.

Artists for Rent Control

is, admittedly, a small and disparate handful of anarchist or socialist

musicians, graphic artists and other folks based here in Portland,

Oregon and around the world. We believe that while there is a dire need

for door-to-door neighborhood organizing, there is an equally dire need

for popular education. Rent strike organizing will not become

widespread just because people are desperate. These material

circumstances need to be joined by the understanding that another world

is possible. That things don’t have to be like this. That there are

other, real, functional and functioning alternatives to be found in many

other countries, right now today, that work much, much better than our

collapsing house of cards ponzi scheme economy, administered by a

kleptocratic government controlled by real estate industry lobbyists who

have systematically engineered the whole ponzi scheme to be a ponzi

scheme in the first place. One of the many things the developer lobby

has accomplished over the course of the past forty years or so has been

to completely eliminate, or at least totally eviscerate, rent control

laws in all fifty states.

People need to know about this. People need to know that there are

alternatives to this cutthroat, profit-over-people economic model that

has recently been dramatically exposed as a completely failed model, in

terms of sustaining human life, the most vulnerable of which we are

losing daily, in vastly disproportionate numbers, to the ravages of the

housing market that has been exposed by this pandemic, with those dying

the most being the ones living in the shittiest housing in the most

neglected, decaying, rat-infested, overcrowded apartment blocks of New

York and Detroit, along with all those living without running water or

electricity in places like the Navajo reservation, or the farmworkers of

the Yakima Valley, currently on strike. Or again, in Detroit.

People need to know that most wealth is inherited. That the landlord

class has created this situation of inequality through a legalized

system of bribery called lobbying. That they make their record profits

not by doing anything useful, but by sitting on money and property that

has been passed down in wealthy families from the US and other countries

for generations. That they raise the rents according to a formula they

come up with, as wages rise, to make sure there’s that “sweet spot”

between evictions and those who are just barely able to pay, so they can

maximize their profits as they maximize our misery. This is systemic,

it is intentional, it is feudalistic, and it is so very wrong.

And it doesn’t have to be this way. Another world is possible — hether

your landlord is a big corporation like mine is, owning hundreds of

properties up and down the coast, or a so-called “mom-and-pop” landlord

(a rich peasant,

to use a Chinese analogy) who has taken advantage of the pro-landlord

housing market to live off of your labor through charging you a “market

rate” rent, despite the fact that their mortgage may have been paid off

decades ago. Society can and must be restructured. This will

inevitably involve a lot of government intervention, which government

will do to save itself and to save capitalism, just like with FDR. But

that won’t happen until we make it happen, through rent strikes and

general strikes, among other vital tactics.

And that won’t happen until people believe that this kind of change is right.

In the US in particular, this presents what I would call our biggest

obstacle. A far bigger obstacle than the circumstances of the pandemic

presents, and a far bigger obstacle than that of actually organizing

people to work together. The biggest obstacle is our minds — our

American minds, which have been force-fed so-called “free market” values

from birth.

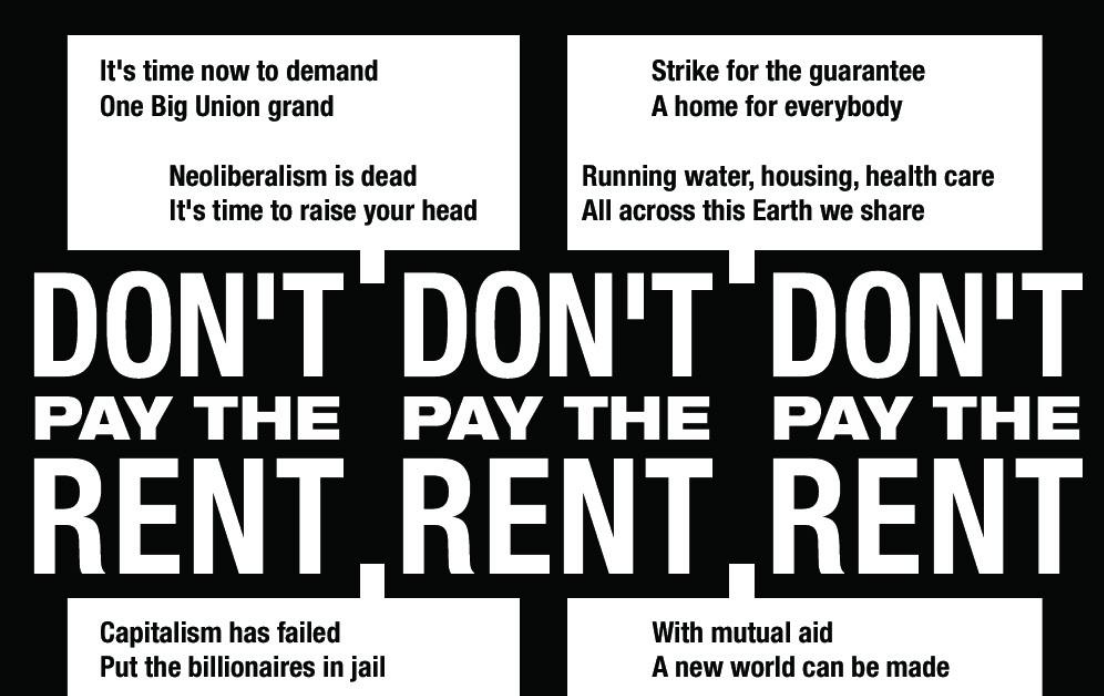

So, this is a call to arms. My personal weapon of choice is a staple

gun. We can all do our best to spread ideas — through music, art,

photography, videos, essays, etc. — on the internet. But physical

space is the space we’re talking about having control over — housing.

And we have to be in those physical spaces, too. This is why we have

been plastering many neighborhoods of Portland with informational (and

rhyming) posters, questioning the failed values of capitalism,

encouraging people to think about how society could be done differently,

and encouraging people here in Multnomah County not to pay the rent,

which is the first step in this inevitably jagged and tumultuous

transformational process that must be undertaken if our species is to

ultimately survive in any recognizable form.

While we have very limited resources in every possible sense as a

network, Artists for Rent Control has two main aims, and your

participation, in whatever form possible, is wanted. One, we aim to

keep our messages visible on the telephone poles of Portland. You can

print out posters and put them up yourself, ask for a shipment of them

from us, or donate for printing press costs. The other main aim of the

network, in the tradition of similar networks of unemployed workers in

the past, will be to react quickly to any attempted evictions going on

in the area, once they start happening. To that aim, we’ll soon have

our website set up so that anyone with a phone can sign up to receive a

push notification when there is an eviction attempt taking place, so

that they can drop everything and rush to wherever this is happening,

and hopefully prevent the eviction from occurring. For this to be

effective, we’ll need thousands of Portlanders to sign up. For that to

happen, we’ll need thousands of Portlanders who believe that another

Portland, and another world, is possible. And we’ll need to convince

them of this fact.

I have personally been roving the streets of Portland for weeks now,

spending hours most days putting up posters, close to a thousand

altogether so far. This itself has been a fascinating experience. The

lockdown of society has been serious around here, and very few members

of the public are generally in the streets, but the reactions I

have gotten from people as I’ve been putting up posters have been

overwhelmingly positive. Many, many people are unaware that there is a

suspension on evictions. Their landlords, in most cases, have not told

them anything. If they opened a piece of mail they may have received

from a neighborhood association about it, then maybe they know. Or if

they listen to NPR on a daily basis, they may have been listening on the

right day, so they heard about the ordinance. But it’s not getting a

whole lot of press, for some reason. So by putting up these posters,

we’re providing a basic and needed public service.

Other reactions have been less positive, and generally comes in the form

of posters being quietly taken down — never when I’m looking, and, as

far as I can tell, almost always in the dark of night. If you look up

the laws in Portland on this kind of postering activity, you’ll find

it’s illegal, but very mildly so. It’s not considered a real crime, but

more on the level of a nuisance. People who are bothered by things on

telephone poles in their neighborhood have the option of complaining to

the city authorities, which say on their website that they will send

someone to take down the offending items within 72 hours. Whether it is

city workers or employees of a property management company, posters

that are nearby really shitty-looking apartment complexes full of

oppressed-looking renters get taken down fast. Posters put up in almost

any other neighborhood, even on very busy streets, have often been

staying up for weeks. For the record, the cardstock that Minuteman

Press uses will still look good after several serious downpours, and the

ink won’t start running for at least a month.

What is especially notable to me is the postering I was doing for

progressive city council candidates, also during the lockdown, resulted

in those posters getting ripped down in every neighborhood I put them up

in, presumably by passersby who either don’t like progressive

politicians, or, I suspect, by people who just don’t like any politicians,

and are annoyed by the claims any politician might make about doing

anything useful, since many people just assume they’re lying in order to

get votes. An assumption that I’m convinced does not apply to, say, City Councilor Chloe Eudaly, but certainly does apply to most politicians, so it’s an understandable and even perhaps laudable reaction to such a poster, generally.

Not so with the informational posters we’ve been putting up that feature

the phrase “don’t pay the rent” in the center. Whether people are

paying the rent or not, very few people seem to be bothered by the idea

of not doing so. That, all by itself, is a good sign.

I get a lot of raised fists and shouts of encouragement from renters of

all ages and in all neighborhoods, wherever I put up these posters — as

well as, of course, people who are minding their own business and

moping down the sidewalk without stopping to read them. But the one

negative reaction I got from someone who actually stopped to say

something to me other than “yeah” or “right on,” was a middle-aged woman

who was out walking her dog, who read the central line of the poem (not

bothering to read any of the rest) and repeated it in horror.

“Don’t pay the rent?” she asked. “Why not?”

I gave her the one-sentence version of my speech.

“Many people can’t pay the rent right now, and so while there is a

suspension in evictions, if the rest of us also don’t pay the rent, we

may have a window of opportunity now to force the government to do what

many governments have already done in European countries — defer

mortgages and cancel rents for the duration of the crisis.”

She responded.

“I own a duplex down the street, and I don’t know what I’d do if my

renters stopped paying the rent. Deferring my mortgage wouldn’t really

help me. I don’t have a mortgage.”

In other words, she makes a living mostly or entirely by exploiting the

fact that she owns a duplex, which she may or may not have inherited,

but which is entirely paid off. Without needing to charge so much rent,

she makes enough money from renting one house to make a living

herself. She is a professional rich peasant.

I didn’t respond directly to her situation, not wanting to make any

inaccurate assumptions, and not wanting to appear unsympathetic. I

started talking about my own landlord, to put the situation into a

context that is especially relevant for most renters these days on the

west coast.

“My landlord is a corporation that owns hundreds of buildings. They’ve

been raising the rent so much every year that my rent is now more than twice what it was when we moved in in 2007.”

Her response then was so telling, and summed up the problem — and the solution — fairly neatly.

“That’s just how it goes,” she said.

No, rich peasant. No, “mom-and-pop.” No, corporate investor. No,

house-flipper. No, real estate developer, banker, financier, corrupt

politician, and everyone else — no. It’s not “just how it goes.” It’s

not how it goes in civilized countries, and it doesn’t need to be how

it goes in this one. Real rent control is possible, and we can do it

here, too. It starts with a rent strike. It ends with victory. Join

us.

David Rovics has been called the musical voice of the progressive movement in the US. Since the mid-90’s, Rovics has spent most of his time on the road, playing hundreds of shows every year throughout North America, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East and Japan. He has shared the stage regularly with leading intellectuals, activists, politicians, musicians and celebrities. In recent years he’s added children’s music and essay-writing to his repertoire. More importantly, he’s really good. He will make you laugh, he will make you cry, and he will make the revolution irresistible. Check out his pamphlet: Sing for Your Supper: A DIY Guide to Playing Music, Writing Songs, and Booking Your Own Gigs