By Peter Marshall

The ‘Jefe Maximo’ (Supreme Leader) Fidel Castro is dead. He may have become been a towering figure in the 20th century but for many he was a highly controversial and divisive one. His brother Raúl, aged 85 and head of the military forces, continues as president of Cuba. The ‘Communist’ regime totters but for the moment lives on.

The Cuban Revolution in 1959, against the corrupt dictatorship of Batista which had turned Cuba into a playground for rich Americans and was run largely by the Mafia, was a genuine revolution. It eventually nationalised American-owned industries, provided food for all, brought about greater social and racial equality, and delivered free medicine and education. But they were at a cost.

Castro, with Che Guevara, at his side, at first promised free elections but soon the regime declared itself as Marxist-Leninist and was ruled by the Communist Party with Castro at its helm. It became forever closer to the Soviet Union with which it exchanged sugar and tobacco (its principal products) for oil and weapons. Increasingly, it became a thorn inside the US government, a troublesome boy in its backyard.

Although anarchists and libertarian socialists at first supported the revolution which seemed popular and from below, they were early on imprisoned or forced into exile. The explosion of experimental art and film soon felt the dead hand of censorship. Castro and the regime allowed no dissent, and outlawed any person who was not seen as a straight revolutionary like themselves, particularly lesbians and homosexuals.

At the same time, Cuban forces repulsed the US-backed invasion of Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs. Castro survived many CIA attempts on his life, including, famously, an exploding cigar. In the 1962 the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Castro allowed Soviet weapons on its soil, brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. J.F. Kennedy was ready to use nuclear weapons if the missiles were not withdrawn, and Castro admitted later that he was prepared to see Cuba destroyed and a good part of the human species obliterated if the Americans invaded the island. Khrushchev, however, blinked first and the nuclear missiles were withdrawn.

The Cuban regime became a great exporter of revolution, particularly to Africa and South America. Its involvement in Angola certainly speeded up the demise of the South African apartheid regime. As is well known, Che Guevara, an icon of his age, died in the jungles of Bolivia, forever a guerrilla of international socialism. He may have promised to turn work into ‘meaningful play’, create the ‘New Man’(sic) and wished to motivate people by moral rather than material incentives, but this has not come to pass in Cuba nor elsewhere.

In more recent times, Mandela of South Africa, Hugo Chávez, former president of Venezuela, and Evo Morales, president of Bolivia, have among others admired Castro and his regime. But despite the tinkering of President Obama, the American economic blockade remains in place and Guantánamo Bay is still open. Trump has called Castro a ‘brutal dictator’. The slight thaw in relations between America and Cuba is unlikely to continue for the time being.

I have written two books about Cuba, one called Into Cuba, with the photographer Barry Lewis, and the other entitled Cuba Libre: Breaking the Chains? They were based on several visits to the country in the eighties. The former book went through two editions and was translated into three languages, and published in the US by Alfred Van Der Marck. The latter went through three editions and was published in the US by Faber and in Spanish by the Mexican publisher Diana. I was interested at the time in so-called independent examples of socialism. It was even arranged for me to meet Castro but instead I had to content myself with the Minister of Culture who had fought with him in the hills.

The question – ‘Breaking the Chains?’ – is crucial. In both books I tried to show that the Cuban Revolution is very recent and, for many centuries, Cuban society and culture evolved independently in a wonderful mix of what has been called the African drum and the Spanish guitar. The revolution itself has undoubtedly brought many gains, notably in greater solidarity with other countries and at home, in social and racial equality and in free education and medicine (with literacy rates and life expectancy comparable to those of Europe).

At the same time, it has been at a terrible cost, with dire curbs on personal autonomy and the freedom of thought, expression and assembly.

I do not want to go back to the island, despite my appreciation of the Cuban people and their deep-rooted culture, as long as the Castro regime and family are in power. The country remains a one-party, top-down State ruled from the centre by obscure and dogmatic bureaucrats with their fingers in all aspects of everyday life.

The great tragedy of the Cuban Revolution is that the original libertarian and democratic ideals have not been realized. Perhaps they will be one day. One can always hope.

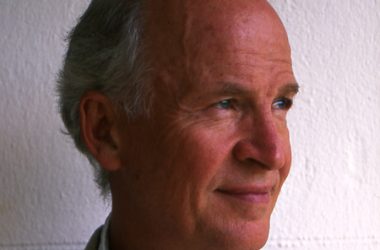

photo by Alberto Korda, 1961