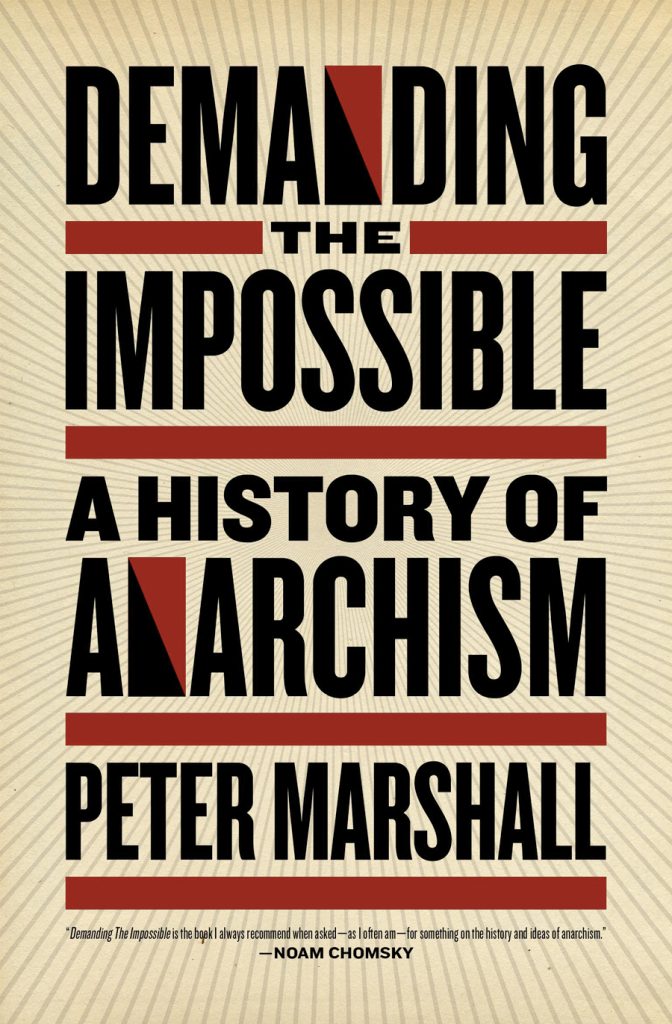

By Peter Marshall

July 27th, 2020

It’s time to

remember the great connection between the earth and the heaven, the

microcosm and the microcosm. ‘As above, so below’, as they say in

alchemy.

It is important as this time of year to celebrate

joyously the Midsummer by the megaliths, particularly close to any

stone circles.

One should also celebrate in the great ‘Wheel

of the Year’ the other equinoxes in the spring and autumn, and the

winter solstice, as well as the cross quarter days in between, since

they are markers of the sun’s movement throughout the year, of the

movement of life itself on earth.

As I wrote in a book called

‘Nature’s Web’, an exploration of ecological thinking, we are not

separate from Nature but part of the whole. We should therefore

recognize that Nature has value-in-itself, not merely as a means to

our narrow human ends. We should therefore have Reverence for Nature,

for the land and sea and the heavens, for the place in the universe

where we live.

I have celebrated the rising of the sun at

Stonehenge in Britain on the Summer Solstice, when the sun is closest

to the earth in the northern hemisphere. I have regularly welcomed in

the dawn in the Summer Solstice in the megalithic complex at

Merrivale on western Dartmoor where I used to live.

This

year, I celebrated the rising of the sun by a circle on a clifftop

overlooking the sea in east Devon where I now live. The stone

circles, avenues, tombs, dolmens and menhirs (standing stones) in

Britain and elsewhere in Europe are usually said to belong to the

Neolithic (the New Stone Age) from about 4,500 BCE (that is before

the Common Era which was formerly known as BC, before the Birth of

Christ) and the Bronze Age (from roughly around 2,500 BCE, following

the short-lived Copper Age). The stones went up when people settled

down and practised agriculture. But they were probably in places of

special earth energy, held sacred already by hunter-gatherer peoples

in their annual migrations well before them.

I have written a

book called ‘Europe’s Last Civilization: Exploring the Mysteries of

the Megaliths’. It covers a voyage in a small yacht with my companion

from Scotland to Malta, visiting all the great megalithic sites on

the way. It is part of my hypothesis that the megaliths were built by

the sea or rivers, including Stonehenge, since water was the

principaI means of transportation at the time when inland it was

densely wooded. They were later temples in the Balearic Islands in

the Mediterranean and much earlier ones in Malta, but the same method

of building stone megaliths took place from the late Neolithic age

all down the Atlantic Seaboard and into the Mediterranean as far as

the foot of Italy.

I call deliberately the society of

megalith builders a ‘civilization’, while popularly it is often

seen as a ‘primitive’ product of the Stone Age when men and women

were dressed in furs and skins and lived in caves. Nevertheless, it

is a civilization, since during the Late Stone Age and the Early

Bronze Age many great stone monuments were raised to the sky by

members of a society who showed a deep understanding of the movement

of the planets and stars, had a complex religion and a rich social

life. It was far from ‘primitive’ as is usually understood;

instead, I would argue it was highly civilized.

The root of

the word ‘civilized’ comes from the ancient Greek ‘civis’, of

the city, but clearly many of these monuments were constructed by

people living in villages who worked together, shared their wealth

and had sufficient leisure time to build such wonderful and magical

structures.

Above all, for me it was a great

civilization of peace. The monuments were not defended which implies

there was no need to since there was no war amongst different groups.

As I have said, the megaliths went up when people settled

down to agriculture in about 4,500 BCE in northwest Europe but much

earlier in the so-called ‘Fertile Crescent’ in the Middle East. I

have personally visited Çatalhöyük near the south coast in Turkey,

dating from about 7,000 BCE, which reveals the remains of a large

settled town.

I have also been to the even more intriguing

monument of Göbekli Tepe in eastern Turkey close to the Syrian

border. Its stone temple dates from about 9,000 BCE and has realistic

carvings and reliefs of local animals as well as being orientated

towards the heavens. It may have been made by settled people or even

hunter-gatherers who met there on their annual migrations. In other

words, the stones are very ancient and show a profound awareness of

our place in the universe and the need to revere Nature as a whole.

Indeed, it may well be that the hunter-gatherers had the

greatest ‘civilization’, as some so-called ‘primitivists’ have

argued, as they had robust health, practiced no war between

themselves, and lived in comparative equality. In many ways, they are

a model to us, living in a condition of peaceful, mutual aid,

egalitarian anarchy, without coercive laws, state and government.

Even so, I would argue that the Neolithic period of

monumental building in stone when people were practicing agriculture

was at first the greatest ‘golden age’ as there seemed to be

little hierarchy and domination, with communal property and graves,

as well as lasting peace. The French writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau was

only partly right when he said ‘It was iron and corn which first

civilized men and ruined humanity.’

History changed during

the Bronze Age from about 2,500 BCE in Europe, and during the Iron

Age from about 800 BCE which followed, when priests and chiefs

emerged with classes, hierarchy and private property. We can see then

individual burials rather than communal ones. They had rich grave

goods which imply the importance given to special individuals.

Many

of the stone circles were later called ‘Druid circles’.

The

Druids are normally seen as priests of the Celts who may have come to

these islands from central Europe from around 800 BCE in the Iron

Age. According to the Roman and Greek sources, the Druids wrote

nothing down and relied on memory to teach their doctrines, but they

apparently believed in the transmigration of souls or reincarnation

very much like contemporary Hindus, Jains and Buddhists.

According

to Julius Caesar, after the Roman invasion of Britain, the Druid

priests formed a separate group in society as political advisers,

healers and arbitrators between warring Celtic tribes. Their rites

and observances often took place in oak groves and in liminal places

near water.

Julius Caesar said they practiced animal and

human sacrifices, but this description could be the attempt of

conquering Romans to deem them ‘barbarians’ in order to impose

their rule, very much like Europeans did in the 17th, 18th and 19th

centuries to peoples they encountered who did not have the same

advanced technology and efficient weapons.

The Celts were

certainly very warlike and fought among themselves. They may have

been invaders in Britain or just had a very strong cultural influence

or both. You can see that especially in their art with its interlaced

designs.

I lived in North Wales with my family for 21 years,

first in a remote cottage in the mountains then by the Irish Sea. It

was in the county of Gwynedd, the heartland of Welsh speaking

communities. My children are fluent in Welsh and I speak some of the

ancient language. Many of my Welsh neighbours and friends called

themselves Celts as opposed to the Anglo-Saxon English who conquered

them and tried to make them speak English. I am also about a third

Irish (I had an Irish grandmother on my father’s side) and have

sailed around Ireland, written up in a book called ‘Celtic Gold’, so

am steeped in Celtic culture and traditions.

I understand

that modern Druids are mainly concerned with peace and healing and

the reconciliation of warring parties. They take up ancient wisdom

and stand in the Bardic tradition and particularly celebrate poetry,

story-telling, song and dance. Like the followers of Wicca and the

Earth Goddess, witches and neo-Pagans, they wish to follow a

spiritual path keeping in close touch with the living Earth and

Nature.

I am not a Druid myself. But I’m sure the Celts and

Druids took up many aspects of the ancient religion of the megalith

builders and took over many of their stone circles for their worship

and celebrations. I myself share a similar world view to the ancient

megalith builders who lived in peace and co-operation and who seem to

have believed in a form of pantheism, that is to say, that God is

imminent in nature, or as Spinoza would call it later, God is Nature.

As the Chinese Taoists say, the Tao is to be found

everywhere, ever-present in Nature. The Tao cannot be defined but

only felt and understood. The modern equivalent is probably the

concept of Gaia which I espouse as well as the Tao.

Peter Marshall is a philosopher, historian, biographer, travel writer and poet. He has written eighteen highly acclaimed books which are being translated into fourteen different languages. His circumnavigation of Africa was made into a 6-part TV series and his voyage around Ireland into a BBC Radio series. He has written articles and reviews for many national newspapers and journals.