By Jenny Turner

The Guardian UK 33, no. 24

December 15, 2011

Young

women, the state and public order in Britain, as seen in clippings from

the newspapers, August 2011: Natasha Reid, 24, pleaded guilty to

stealing a television from a Comet in North London during the riots of

August 7. Her mother said she was “baffled” by her own behaviour—she had

a much nicer TV set at home. Shonola Smith, 22, pleaded guilty, along

with her sister and a friend, to “entering” Argos in Croydon: “The

tragedy is that you are all of previous good character,” the judge said,

as he sentenced them to six months each. Chelsea Ives, the 18-year-old

“shamed former Olympic youth ambassador” shopped by her mother, pleaded

guilty to criminal damage and burglary on the Sunday, and to violent

disorder (a Somerfield in Hackney) the following evening. “The public

seem to automatically place me in an unnamed category for thick,

low-life individuals, which is not me at all,” Chelsea wrote “from

behind bars” in a letter intended for the novelist Gillian Slovo, but

which the Evening Standard used as an occasion to run her

big-hair camera-phone-in-the-mirror Facebook picture yet again. She

began a two-year jail sentence this month.

Here, in a nutshell,

is the problem with feminism. Young women “of good character” losing

their heads and wishing they hadn’t. You feel so sorry for them, but

can’t you sense what they tasted in the air as they were doing it:

freedom, fury, the power—for once—of being young and strong and agile

and a homegirl, the flat-out joy of getting your hands on some free

stuff. “This is the best day ever,” Chelsea said, while looting the

T-Mobile store. “Trainers, clothes, mobiles, iPods, Macs—possession of

these things is tantamount to human rights,” a writer called Charmaine

Elliot posted on Blackfeminists.blog, remembering her own youth in

London.

“I took a trip to Selfridges one afternoon to visit a

friend and was struck by advertising slogans that said, à la Barbara

Kruger, I shop, therefore I am. And I couldn’t help but wonder that as I

couldn’t actually shop, ergo what?”

At the UK Feminista

summer school in Birmingham meanwhile, Emily Birkenshaw, 24, a teaching

assistant from York, was learning how to “go floppy” when arrested.

“You’re heavier then, so you can’t be carried,” she told the Observer. “It just felt really empowering.” UK Feminista was launched last year by 29-year-old Kat Banyard, whose first book, The Equality Illusion,

came out at much the same time. “The event is set to harness the recent

upsurge in interest in this previously unfashionable social movement,” a

press release for the summer school said. In June UK Feminista had joined forces with Object

(the stress goes on the second syllable, “I ob-ject”), another newish

bright-young-feminists organisation, to campaign against the recent

opening of a Playboy nightclub in London. “Eff off Heff, stop degrading

women!” protesters chanted. “No more sexist men, Playboy empire has to

end!”

Look at them on YouTube, having their genteel shout and

waving their Ban the Bunny placards: “Ob-ject, women not sex objects.”

“That’s not what empowerment looks like/This is what empowerment looks

like!” Idealistic, well organised, compassionate and let-them-eat-cakey,

these young women have no place on their neat clipboards for

disturbance, unintended consequences, humour or even humility when faced

with the pressures and precariousness of most people’s lives.

More from YouTube, late September.Object

and UK Feminista have been busy, dressing up in white overalls with red

ink on their faces, waving cleavers outside the XBiz pornography trade

show in Bloomsbury: “Just a bunch of pimps and butchers/ Who trade in

women’s lives!” A small bearded man shouts at them bitterly, an XBiz ID

card round his neck, a bottle of Stella in his hand. “You’re a bunch of

whores!” he snarls. “I’m gonna fuck you all up the arse!”

“Pornography

today is increasingly violent, body-punishing, degrading and

woman-hating,” it says on Object’s press release, which is both true and

completely beside the point. It’s a free-market economy out there, so

of course there’s going to be violent pornography as long as there are

people fucked up enough to want it. And of course there are people

prepared to make it for them. The American writer Laura Kipnis warns

against getting “teary-eyed about exploited pornography workers” when

you “haven’t thought much about international garment workers, or

poultry workers—to name just two.” Which is funny, because the girls

from UK Feminista were wearing the hats you wear to gut chickens and

pull their claws off. It’s even funnier if you remember that two of

porn’s most successful crossover stars both front animal-rights projects

that attack the poultry industry in particular: the Playboy model and

actress Pamela Anderson (Baywatch, Borat) and the hardcore queen Jenna Jameson, for Peta’s Kentucky Fried Cruelty and McCruelty (I’m hatin’ it) campaigns.

Chicken

pieces, iPods, A-level burb girls with jobs in Selfridges, unable to

buy any of the stuff they sell: how often if ever are such things

addressed by Object and UK Feminista? How important is being female to a

young woman’s everyday life and future prospects, compared to being

born in the 1990s, or being Somalian, or good-looking, or receiving EMA,

or going to Oxbridge, or not getting a single GCSE? “To put it

schematically: ‘women’ is historically, discursively constructed, and

always relative to other categories which themselves change.”

Thus the British poet-philosopher Denise Riley in Am I That Name? (1988),

her short, playful, brilliant study of the many ways in which fixed

identities never work. “That ‘women’ is indeterminate and impossible . .

. is what makes feminism,” Riley concluded, so long as feminists are

willing “to develop a speed, foxiness, versatility.” Can the members of

Object and UK Feminista welcome such transformations, or is this what

they are afraid of: that if they let themselves really look at the world

around them, feminism as they think they know and need it might

completely disappear?

“Enough ink has been spilled in quarrelling

over feminism . . . perhaps we should say no more about it”: Simone de

Beauvoir, at the very beginning of The Second Sex (1949). “The

subject is irritating, especially to women.” Long before they were

shouting “Ban the Bunny” and dressing up as butchers, feminists were

annoying people, not just misogynists and sexists, but the very people

you’d think would like them best. It was true in suffragette days, as it

was during Women’s Liberation in the 1960s and 1970s, and it’s very

much a problem for what boosters have been calling “the third wave”

since the early 1990s. We know the angry squiggles that signify this

irritation—the hairy-legged Millie Tant man-hater, Mrs. Banks in the

Disney Mary Poppins, a suffragette too busy to care for her children.

And it’s obvious how useful such stereotypes have been in neutralising

the threat felt in the wider culture. But these caricatures obscure a

real problem: a confusion between self and other, identity and

difference, that you might charitably view as an unfortunate side-effect

of being of and for and by women, all at once; or, less charitably, as

narcissistic self-absorption.

It’s true that women, as a gender,

have been systemically disadvantaged through history, but they aren’t

the only ones: economic exploitation is also systemic and coercive, and

so is race. And feminists need to engage with all of this, with class

and race, land enclosure and industrialisation, colonialism and the

slave trade, if only out of solidarity with the less privileged sisters.

And yet, the strange thing is how often they haven’t: Elizabeth Cady

Stanton opposed votes for freedmen; Betty Friedan made the

epoch-defining suggestion that middle-class American women should dump

the housework on “full-time help.” There are so many examples of this

sort that it would be funny if it weren’t such a waste.

Not that

the white middle-class brigade like being on the same side as one

another. There’s always a tension between all of us being sisterly, all

equal under the sight of the patriarchal male oppressor, and the fact

that we aren’t really sisters, or equal, or even friends. We despise one

another for being posh and privileged, we loathe one another for being

stupid oiks. We hate the tall poppies for being show-offs, we can’t bear

the crabs in the bucket that pinch us back. All this produces the

ineffable whiff so often sensed in feminist emanations, those anxious,

jargon-filled, overpolite topnotes with their undertow of envy and

rancour, that perpetual sharp-elbowed jostle for the moral high ground.

Looked

at one way—in the manner of Joan Didion, for example, in her harsh,

oddly clouded but startlingly acute essay of 1972 on the Women’s

Movement—the idea of feminism is obviously Marxist, being about the

“invention,” as Didion put it, “of women as a ‘class’,” a total

transformation of all relationships, led by the group most exploited by

relations in their current form. So why did the libbers so seldom say

so? Well, some came to the movement as Marxists, and did. Sheila

Rowbotham wrote that “the so-called women’s question is a whole-people

question” in Women’s Liberation and the New Politics (1969);

then in 1976 Barbara Ehrenreich stressed that “there is no way to

understand sexism as it acts on our lives without putting it in the

historical context of capitalism.” Others shoved the categories in great

handfuls through the blender: “sex-class” must “in a temporary

dictatorship” seize “control of reproduction” according to Shulamith

Firestone in The Dialectic of Sex (1970).

More

prevalent, however, was what Didion called a “studied resistance to the

possibility of political ideas”—who, in any case, ever heard of a

radical-feminist movement taking its understanding of historical change

from a man? The entire Marxist tradition was repressed, leaving a weird

sinkhole that quickly filled up with the most dreadful rubbish: wise

wounds, herstory, nature goddesses, raped and defiled; sisters under the

skin, flayed and joined, like the Human Centipede, in a single biomass;

the fractal spread of male sexual violence, men fuck women replicated

at every level of interaction, as through a stick of rock.

And so

Women’s Liberation started trying to build a man-free, women-only

tradition of its own. Thus consciousness-raising, or what was sometimes

called the “rap group,” groups of women sitting around, analysing the

frustrations of their lives according to their new feminist principles,

gradually systematising their discoveries. And thus that brilliant

slogan, from the New York Radical Women in 1969, that the personal is

political, an insight so caustic it burned through generations of

mystical nonsense—a woman’s place is in the home, she was obviously

asking for it dressed like that. But it also corroded lots of useful

boundaries and distinctions, between public life and personal burble,

real questions and pop-quiz trivia, political demands and problems and

individual whims. “Psychic hardpan” was Didion’s name for this. A

movement that started out wanting complete transformation of all

relations was floundering, up against the banality of what so many women

actually seemed to want.

Across the world, according to UK

Feminista, women perform 66 percent of the work and earn 10 percent of

the income. In the UK two-thirds of low-paid workers are women, and

women working full-time earn 16 percent less than men. All of this is no

doubt true, but such statistics hide as much as they show. One example.

In a piece in Prospect in 2006, the British economist Alison

Wolf showed that the 16 percent pay-gap masks a much harsher divide,

between the younger professional women—around 13 percent of the

workforce—who have “careers” and earn just as much as men, and the other

87 percent who just have “jobs,” organised often around the needs of

their families, and earn an awful lot less. Feminism overwhelmingly was

and is a movement of that 13 percent—mostly white, mostly middle-class,

speaking from, of, to themselves within a reflecting bubble.

In Feminism Seduced,

the American sociologist Hester Eisenstein, a self-confessed

“professional feminist,” writes that she is “unhappily” aware that

feminist politics have become “all too compatible” with the globalised

free market and the neoliberal thinking that promotes it. Feminists

write books, teach classes, shout slogans, work for NGOs that tell all

manner of “glossy tales” about how unambiguously “empowering” and

“progressive” it is for women to become involved in mainstream economic

life. She finds a real stinker in the UN Population Fund’s 2006 report,

which blandly triangulates “the global care chain,” which, it says,

offers migrant workers “considerable benefits, albeit with some serious

drawbacks;” on the upside, “gifts,” extra cash to send back home, the

chance to travel, and for Muslim domestics in the Emirates the

opportunity, maybe, to do the Hajj.

The reality is very different

for poor women in poor countries—that is, for most of the women in the

world. What options really await them when they get a job? According to

research cited by Eisenstein, there are basically four alternatives:

factory work in export-zone sweatshops, migration, sex work or

microcredit. In the old days, the libbers in their rap groups talked

about Jane O’Reilly’s notion of the ‘click! of recognition’: the sudden

realisation that some nagging problem too dull, too everyday, too basic

even to mention was in fact urgent and shared and politically central.

Reading Eisenstein’s book, the click! comes as a slap.

How has

Western feminism drifted so far out of touch? By narrowing its focus,

Eisenstein thinks, to culture and consciousness and personal testimony,

neglecting what she calls “the political economy of feminism,” and in

particular the economic peculiarities that caused Women’s Liberation to

happen where and when it did. Never mind the Pill, the miniskirt, the

“problem with no name,” Eisenstein says: all that is a sideshow. The

rise of Western feminism came about because there was a widespread

shift, around 1970, of middle-class women from the home to the

workplace: partly, no doubt, because they sought fulfilment and

financial independence, but mostly because wages overall were in

decline. Women entered the workforce bigtime, in other words, just as

the “long boom” of the postwar years was ending, and since most women

get lower-paid jobs anyway—part-time and casual, unskilled,

mommy-track—most of them went ‘straight up the down escalator’, the

phrase coined by the economic historian Teresa Amott. This is the way it

has been for most women ever since.

Feminism, according to the

sociologist Angela McRobbie, has been “disarticulated” and “undone,”

bits pulled out, reworked and retwisted, and other bits dumped. At the

moment, the popular elements include “empowerment,” “choice,” “freedom,”

and, above all, “economic capacity”—the basic no-frills neoliberal

package. It’s fine for any ‘pleasingly lively, capable and becoming

young woman’ to aspire to this. It doesn’t matter if she’s black or

white or mixed race or Asian, gay or straight or basically anything, so

long as she is hard-working, upbeat, dedicated to self-fashioning, and

happy to be photographed clutching her A-level certificate in the Daily

Mail. This young woman has been sold a deal, a “settlement.” So long as

she works hard and doesn’t throw bricks or ask awkward questions, she

can have as many qualifications and abortions and pairs of shoes as she

likes.

“Why a book?” Louis Menand asked recently in the New Yorker, in an article about how the 1963 publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique—about

rich, educated suburban housewives suffering from “the problem with no

name”—became “the catalyst for a social change.” “But why a book? Why

not a court case, or a boycott, as in the case of the civil rights

movement—something that challenged existing law?” Perhaps, he

speculates, it was “because the book was a medium that women had

relatively unobstructed access to as authors and as readers.” Never mind

Emma Goldman and her dancing: for revolution to reach middle-class

women in the early 1960s, it had to be something you could get on with

in the home between the vacuuming and the cocktails. This “books as

bombs” hypothesis only works for middle-class women, of course.

Working-class women would not be lounging around of an afternoon, but

out working, maybe cleaning or doing childcare for a richer woman who

was busy reading or finding herself or getting herself a little job.

“People

like to be able to point to a book as the cause for a new frame of

mind,” Menand argues, “possibly for the same reason that people prefer

anecdotes to statistical evidence. A book personalises an issue. It has

an Erin Brockovich effect.” People don’t want especially true or new or

risky ways of thinking about feminism, they just want one of

Eisenstein’s “glossy tales” with a part for Julia Roberts. If feminism

wants to make sense to the people of the reflecting bubble, it has to

present itself as a traditionally feminine narrative genre, as sleek

high-end infotainment, with showbiz gossip, glamour, stars.

It’s

possible to disagree with this completely while also seeing that Menand

is sort of right. Feminist ideas circulated in the 1960s and 1970s

through books, magazine interviews and the new form of television chat

shows. A montage in Women, a documentary series by Vanessa Engle

broadcast by the BBC last year, showed the big bang underway. The former

child actor Robin Morgan (Sisterhood Is Powerful, 1970), wry and ready for her interview in enormous tinted shades; Susan Brownmiller (Against Our Will,

1975), calmly browbeating a smarmy male editor during the Ladies’ Home

Journal sit-in of 1970. And Germaine Greer, of course, a feather-cut

hipster dryad: “It’s a cinch to have an orgasm. I can give an orgasm to

my cat!” And ever since, this book-as-bomb model has come to stand for

the progress of feminism in general: Naomi Wolf (The Beauty Myth, 1990), Susan Faludi (Backlash, 1991), Ariel Levy (Female Chauvinist Pigs, 2005)—big-selling first books by American upper-journalists, young and clever and energetic, bright-eyed and bushy-haired.

Unexpectedly,

though, Engle’s film also captured the shadow, a living ghost, of

something else. In one especially mustardy-looking fragment, a young

woman and a toddler in a crochet tabard are seen falling out with each

other in a dingy kitchen, over the foaming horror of the twin-tub

washing machine. It doesn’t say so, but this moment comes from a BBC

film called People for Tomorrow, made by Selma James in 1971

and now available on open access on the BBC website. The film follows

everyday women in Peckham, Belsize Park, Bristol, reflecting on what

might change in their lives and how to go about making this happen, in a

movement that is plain and concrete, but builds into an elegant

dialectic. “It’s very bad for children to just see the woman doing all

this mopping-up process all the time,” the mother is saying in this

fragment. “I’ve been fighting it all my life, my conditioning from my

mother, and here I am . . . doing the very same thing to my two

daughters.”

James’s Wages for Housework movement is

now remembered, if at all, as a frippery, a jokey badge pinned to a

Wolfie Smith lapel. But actually it was an intellectually ambitious

attempt to synthesise Marxism, feminism and postcolonialism, and not

with the usual sellotaped hyphenations. Domestic work, while not

recognised as work because not paid for, is as necessary to the economy

as the waged sort. The workforce needs to be fed, clothed, cleaned for,

comforted, as does its progeny, the workforce of the future. “We place

foremost in these pages the housewife as the central figure,” James

wrote with her co-author, the Italian socialist-feminist writer

Mariarosa Dalla Costa, in The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community (1972).

“We assume that all women are housewives and even those who work

outside the home continue to be housewives. That is, on a world level,

it is precisely what is particular to domestic work . . . that

determines a woman’s place wherever she is and to whichever class she

belongs.”

For many years, the only widely available piece of James’s writing has been this Power of Women booklet,

generally a good sign when you saw it on a new friend’s bookshelf,

small and shocking pink. The film, though, is a better introduction, and

begins with James herself, earphones on and thumping away at her

typewriter: “Like millions of women everywhere, I am a typist. I’m a

housewife, a mother, and I’ve been a factory worker. For twenty-five

years I’ve been involved in revolutionary politics.” She was born in New

York in 1930 and came to Britain in the 1950s as the wife of C.L.R.

James, whom she had met when she was a teenage activist. Her writings, a

selection of which will be published next year, present her politics as

emerging directly from her daily experience. On how C.L.R. helped her

to get started:

“The way to do it,” he said, “is to take a

shoebox and make a slit at the top; then whenever you have an idea jot

it down and slip the piece of paper into the shoebox. After a while, you

open the box, put all these sentences in order and you have a draft” . .

. I knew that if I stayed home from work to put the draft together, I

would end up cleaning the cooker or doing some other major piece of

housework, so I arranged to spend the day at a friend’s house . . . I

had no distractions or excuses. I opened the shoebox, and by six or

seven that evening, just as he’d said, I had the draft of a pamphlet.

The point of Wages for Housework was

not to reduce politics to dirty dishes, but the opposite: dirty dishes

became one index of a job, a role, a domestic ballet that included

“managing the tensions of and servicing in every other way those—women

and men—who do waged work, school work, housework and those made

distraught by unemployment;” absorbing “expressions of anger that are

not allowed elsewhere;” doing the volunteer stuff no one else has time

to bother with, “from church societies to library support groups, from

food co-ops to disaster appeals” and all this going on constantly,

ceaselessly, even more in peasant economies than in richer ones. “The

major part of unseen and uncounted housework,” she added, “is done in

the non-industrial world.” James also tried to uphold a clarity and

honesty about race and class differences among her comrades, without

brooding or sentimentality or presumptuousness or

more-oppressed-than-thou guilt-tripping:

What we’ve been trying

to do . . . is to develop a unified view of the world, that is, a

holistic view of all the divisions among us and how they connect, in

order to build the movement to undermine these divisions . . . We are

divided in many, many ways. Naming and examining those divisions, we can

come to a unified conception of the real relations among us, both

subtle and stark.

James has never been a popular figure in the

Western women’s movement, and is snubbed in most mainstream accounts.

There are accusations of fanaticism, cultishness, sectarian behaviour.

“Like Jehovah’s Witnesses,” Jill Tweedie wrote in a 1976 piece reprinted

in a collection of Guardian journalism, “Selma James and her

sister enthusiasts . . . harangue conferences, shout from soapboxes,

gesticulate on television, burn with a strange fever.” Even Barbara

Ehrenreich gets a little snitty: “Battles broke out between lovers and

spouses over sticky countertops, piled-up laundry and whose turn it was

to do the dishes,” as though there can be no way of thinking about

domestic labour except treating it like a sitcom, with all the sharpest

lines reserved for you.

In People for Tomorrow there is a

conversation, towards the end, between James and a young man, sweet

face and ginger sideburns, out shopping with his permed-and-set young

wife. “How much time do you spend with your children?” Selma asks, off

camera.

“Oh, very little, just one day a week, which is Sunday.”

“Don’t you think you’re missing something?”

The man agrees that he’s missing the children, but “can anyone suggest a better way?”

“Well, that’s what Women’s Liberation is trying to figure out,” Selma says.

“Do

you think it’s worthwhile?” she asks the wife, and the wife says “No,”

and giggles. “We asked her what she thought she might lose,” Selma says,

and the wife says that she just can’t see a man with the children all

day. “I don’t think anybody should be with the children all day long,”

Selma says. “But why shouldn’t he be with the children some of the day

and you some of the day too, and perhaps even together? And perhaps even

in a neighbourhood, all the parents in the neighbourhood helping with

the children?”

“That’s probably a good idea,” the husband says.

“But you’d have to alter the whole structure of work, for instance,

wouldn’t you, to break days up into half-days, as far as work goes?”

“That’s what we want to do,” Selma says. “That’s one of the ideas we want to explore.”

Forty

years on, and the changes are in some ways astonishing: where I live in

South-East London—just up the road from where James filmed one of the

rap groups—it’s quite common to see men caring for children, waged, in

schools and nurseries, and, unwaged, in the home.

Part-time work

is common, as is flexi-time, homeworking, freelancing, multi-tasking.

Equality is regulated by statute. There’s a state-funded nursery and a

Sure Start children’s centre in the primary school across the road;

there are two libraries in easy walking distance, four playgrounds, two

parks; and many other things that, when you look at them from a

distance, make Camberwell look like the New Jerusalem, except that when

you come up close, you see how crummy they are, and compromised, and

half-baked.

Perhaps another reason James gets missed out so often

is because for more than half a century, she has kept her attention

patiently focused on such perpetually disappointing realities. Why keep

having your nose rubbed in all this when you could be reading about

something more amusing instead? And yet, if you stick with it, you’ll

start to see why people like her care so much about public services,

crappy and underfunded though they are, and likely to get so much worse.

They give you a break, a safety net, a respite; and then, granted that

extra brainspace, you can use it to get more. And then, you can work out

how to get more. And more, and more, and more, and more and more.

“Women

only,” it says on the Yahoo page for the London Feminist Network,

another circle on the young-British-feminist Venn diagram. “For all

feminist women” willing to support the organisation in its aims: “to

increase women’s resistance to male violence against women in all its

forms, e.g., r*pe, sexual assault, domestic violence, p*rnography,

pr*stitution, women’s poverty, war & militarism etc.” The vowels

were left out, presumably, in order to stop the page being picked up in

searches for rape, pornography, prostitution—three of the most popular

internet searches. Right from the start, then, the LFN cannot directly

name three of its main critical categories—an act of violence, a mode of

representation, a nasty job. All linked, in all sorts of ways, but

linked just as much to all sorts of other things as well. Rpe,

Prnography, Prstitution. Blanked out, beyond the pale, undiscussable.

The

Rpe-Prn-Prst triangle first came to prominence with the New York

radical feminists of the 1970s—pornography was the theory and rape the

practice, as Robin Morgan said. In her memoir of the period, Susan

Brownmiller writes that it was ‘a miserable coincidence of historic

timing’ that ‘an above-ground billion-dollar industry of hard and

softcore porn began to flourish . . . simultaneously with the rise of

Women’s Liberation,” but there was nothing coincidental about it: they

were both aspects of sexual liberalisation in a market economy. And

something similar is happening at the moment, with panics about

“sexualisation,” “pornification,” and the “commercialisation of

childhood.” Of course businesses will try selling sexy stuff to

children, if they think adult markets are saturated. Of course

pornographers want to break into the mainstream. And of course the

mainstream welcomes such initiatives, because sex is always sexy, and

everybody’s always desperate for something new. And it only gets more

sexy when you claim to be against it, which means you get to talk about

it at length with the added pleasures of disapproval and

self-righteousness. Something of this is surely going on even in Ariel

Levy’s elegant critique of ‘raunch culture’, Female Chauvinist Pigs, and in Natasha Walter’s less judgmental Living Dolls (2010).

Anti-porn porn, basically, with an interesting relationship to

prole-baiting—the word “vulgar” needn’t refer only to a person’s state

of undress.

From Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1981) to the ghastly New Statesman

article of 2000, in which she wrote about her own drug-rape in a Paris

hotel room, the exemplar of this stuff was Andrea Dworkin, who wrote

again and again about sexual victimisation, her own and that of other

women, in fiction and non-fiction, in journalism and memoir. I used to

find it surprising that such a figure got written about so often, and

with such affection, in the broadsheet newspapers, until I realised:

brilliant copy. “Obsessive feminine masochism infused with the ecstasy

of public self-exposure,” in the words of the excellent Laura Kipnis. “A

perfect storm of high-profile narcissism, wrapped in an invitation for

social rebuke.”

What Dworkin’s writing manifestly wasn’t, however, was any sort of thought-through anti-rape campaigning. In the memoir Heartbreak (2002), the last book Dworkin published before her death in 2005, she wrote: “I’ve spent the larger part of my adult life listening to stories of rape . . . I couldn’t move, I could barely breathe—I was afraid of hurting her, the one woman, by a gesture that seemed dismissive or by a look on my face that might be mistaken for incredulity.”

Suppose

you are that “one woman.” Would you turn for help to an egomaniacal

victim-magnet barely able to stop herself dashing off to write about her

pain at your story? Wouldn’t you prefer the company of somebody quiet,

damped-down, unflappable, with that trained social-workerly restraint

that can seem so bland and frustrating, but which comes into its own the

minute someone is actually hurt. “How did I become who I am?” Dworkin’s

memoir continues. “I was torn to pieces by segregation and Vietnam.

Apartheid broke my heart. Apartheid in Saudi Arabia still breaks my

heart . . . I can’t be bought or intimidated because I’m already cut

down the middle.” Andrea Dworkin, a cosmos, multitudinous and

all-suffering in her gigantic dungarees.

Members of the London

Feminist Network featured centrally in the third “Activists” film in

Vanessa Engle’s series Women. “I suppose it all comes down to male

violence against women,” one says. “Sexual violence,” says another. “Sex

trafficking and female genital mutilation.”

“Sexual violence,

in particular domestic violence.” “Porn is like a huge issue for me.”

“It becomes impossible to leave your door without being mortally

offended,” says the beaming and vibrant Finn Mackay, a star activist in

her early thirties. “That is a sick, sick society.”

Mackay says

she first wanted to be a feminist when she was six or seven and heard

about Greenham Common. She left home as a teenager to join another

women’s peace camp, then moved on to build the LFN, Object and the

reborn Reclaim the Night. She’s now writing a PhD about her feminist

activities, goes to a feminist meeting most nights and gets at least a

hundred feminist-activist emails a day. “I have the feminist rage . . .

it’s a bit like taking the blue pill in The Matrix . . . you

understand, you look differently at the workings of society.’ It’s a

language of religion, almost, complete with conversion and regeneration

and separation from the surrounding world.

Denise Riley, as before:

Can

anyone fully inhabit a gender without a degree of horror? How could

someone “be a woman” through and through, make a final home in that

classification without suffering claustrophobia? To lead a life soaked

in the passionate consciousness of one’s gender at every single moment,

to will to be a sex with a vengeance—these are impossibilities, and far

from the aims of feminism.

Further problems with gender

self-saturation were luridly on display in an essay called “American

Electra: Feminism’s Ritual Matricide” by Susan Faludi, published in Harper’s

last year. “American feminism . . . hasn’t figured out how to pass

power down from woman to woman, to bequeath authority to its progeny,”

she argued, and her essay collects a hilarious list of indictments

gathered from “activist gatherings and scholarly conclaves”: “Mean Spirits: The Politics of Contempt between Feminist Generations;” “Are Younger Women Trying to Trash Feminism?”, “The Mother-Daughter Wars;” “Am I My Mother’s Feminist?,” “The movement,”

she claims, “never seems able to establish an enduring birthright, a

secure line of descent—to reproduce itself . . . What gets passed on is

the predisposition to dispossess, a legacy of no legacy.” If Faludi

followed Eisenstein’s political-economy advice, I think she’d find that

half these mumsy metaphors cancelled the other half out.

And yet, this “legacy of no legacy” became a story-arc in Vanessa Engle’s three films. The first film, the delightful Libbers,

cut between archive and contemporary footage, the stars of then as they

are now, hitting old age: Kate Millett, bent double in her Crocs, still

smoking with gusto; Germaine Greer, clucking at her peafowl; Marilyn

French, shortly before her death at seventy-nine, tiny, anguished, very

ill. The figure, though, who spoke most clearly for history was Susan

Brownmiller, watering the houseplants in her New York apartment,

toprocking at her street-dancing class in her mid-seventies: “There’s so

much more that needs to be changed, and the new generation is going to

have to learn that you can only do it really by having a movement. But

they’re also going to learn, and it’s a sad lesson, that you can’t

jump-start a movement—suddenly there’s a critical mass of people wanting

to do something with other people, and you can’t fake that.”

The

second film profiled a bunch of apparently uninteresting middle-class

mothers, bickering about whether in their household the work gets done

by the woman or the man. “In what way are you different from a housewife

in the 1950s?” the voice off-camera asks. The last film was about the

LFN and its sister organisations, and the feminist revival that’s said

to be going on right now. Presumably, evidence of such a movement might

include recent books such as Reclaiming the F-Word by Catherine Redfern and Kristin Aune, which is the book of the F-Word website, and Kat Banyard’s The Equality Illusion. “A new heyday for British feminism,” Kira Cochrane claimed in the Guardian,

a “sudden burst of British feminist publishing after an extensive

drought,” but surely that’s pushing it. So a handful of writers try

their luck at the books-as-bombs business model, as others copy The Da Vinci Code.

And as for feminist blogging, isn’t it just one of those back-bedroom

hobbies, like home-made porn and crafting, that suddenly becomes visible

because the technology allows it? (Zadie Smith on “the great tide of

pornography” in 2001: “It’s not all bad news. We’re talking women whose

sexual desires are no longer sublimated into the making of quilts.”)

Both Redfern/Aune and Banyard try hard to reach younger readers in need

of a basic introduction, and seem to have decided that doing so

necessitates missing out all the interesting stuff, politics and

economics and feuds and splits. I suspect this view may be mistaken.

“Sometimes the things that look the hardest have the simplest answers,” Nina Power writes towards the end of her chapbook, One Dimensional Woman. She then hands over to Toni Morrison speaking to Time magazine

in 1989. On single-parent households: “Two parents can’t raise a child

any more than one. You need a whole community . . . The little nuclear

family is a paradigm that just doesn’t work. It doesn’t work for white

people or for black people. Why we are hanging onto it I don’t know.” On

“unwed teenage pregnancies”: “Nature wants it done then, when the body

can handle it, not after forty, when the income can . . . The question

is not morality, the question is money. That’s what we’re upset about.”

On how to break the “cycle of poverty,” given that “you can’t just hand

out money”: “Why not? Everybody [else] gets everything handed to them . .

. I mean what people take for granted among the middle and upper

classes, which is nepotism, the old-boy network. That’s the shared

bounty of class.”

What about education? If all these girls spend their teenage years having babies, they won’t be able to become teachers and brain surgeons, not to mention missing out on cheap beer, storecards, halls of residence. To which Morrison, with splendour, rejoins: “They can be teachers. They can be brain surgeons. We have to help them become brain surgeons. That’s my job. I want to take them in my arms and say: ‘Your baby is beautiful and so are you and, honey, you can do it. And when you want to be a brain surgeon, call me—I will take care of your baby.’ That’s the attitude you have to have about human life.”

Power, who teaches philosophy at Roehampton University,

comes to feminism from an unusual angle. As a scholar of Marxism and

Continental philosophy she’s well read in the radical-modernist

traditions— thus One Dimensional Woman, from the Marcuse book

about how postwar “liberal democracy and consumerism” dulled and

flattened Western “man.” She’s also one of Britain’s foremost web

diarists, with a superb blog at Infinite Thought since 2004. And she’s a

relative youngster, which means that for her, all that 1960s-1980s

stuff is not a story about herself. For her, the past of feminism is

approached as history, with irony and detachment.

Two points

about Power’s method, with regard to Toni Morrison and other exemplars

from the past. Like her fellow Zer0 author Owen Hatherley, Power has a

curatorial, almost antiquarian attitude to the relics of vintage

radicalism she admires. She writes of ‘the sheer crystalline simplicity

of Morrison’s insights into the relationship between class, race and

gender’. How hospitable, how generous of Power to invite along a

stranger, then sit back and let her take over. How strange and brave of

her also to place such a long and striking quote from such an

unfashionable writer so teeteringly close to standing as her own first

book’s final word. And when you think about it, how explosive of her:

“When you want to be a brain surgeon, call me.” All our assumptions are

flattened by this laconic little statement.

And this, surely, is

only the start. It’s obvious—now Power-Morrison has said it—that any

politics worth having has to start with the nuclear family: its

impossibility, its wastefulness, its historical contingency. Children

are the messages a family, a society, a culture, a civilisation, sends

into the future, and yet every day there comes more evidence that

child-rearing as currently practised among the people with all the

choices doesn’t seem to be working out. They overeat, our little

messages, they starve themselves, they adore themselves when they’re not

indulging in self-harm. They don’t want to study medicine or train as

teachers when they can just be “in the media.” And this obviousness

starts little fires sparking backwards across the decades. There’s Selma

James and the strange marginalisation of her ideas, not to mention the

way the whole family-in-a-house imago goes unchallenged, even by

feminists, lesbian and gay couples, and single-parent campaigners, let

alone in government, advertising, the popular media etc.

This has

not always been the case. A critique of the tight-knit nuclear family

as a breeding-ground of consumerism, neurosis, misery in general, was

central to feminism in the 1970s. This is Adrienne Rich on ‘the

institution of motherhood’ in Of Woman Born (1976): “It creates

the dangerous schism between ‘public’ and ‘private’ life; it calcifies

human choices and potentialities. It has alienated women from our bodies

by incarcerating us in them.” “There is much to suggest,” she wrote,

“that the male mind has always been haunted by the force of the idea

of dependence on a woman for life itself, the son’s constant effort to

assimilate, compensate for, or deny the fact.”

Rich’s book was

extremely influential in its time, and such arguments resulted in the

growth of the nurseries and of shared parenting of 1970s North London,

where attention was given to “children’s health requirements, play

space, schooling, mothers’ housing needs, anything else we could think

of,” according to Lynne Segal. And yet, a few decades later, all this

seems buried, Planet of the Apes style, under heaps of chicklit and Supernanny and I Don’t Know How She Does It,

and the collected purées of Annabel Karmel. How has what went before

been so thoroughly forgotten? The Power-Morrison double act does exactly

what such interventions are meant to, flashing up at a moment of

danger, laying bare the evidence of a crime.

Power makes no

effort to explain how this happened. Instead of choking up on guilt,

anger, scholastic hairballs, she just waves ‘the sheer crystalline

simplicity of Morrison’s insights’ in front of her: water under the

bridge, guys, no need to go on about it, so long as we all do our very

best, from this moment on.

Except that suddenly, last spring or thereabouts, the emphasis of Power’s blog changed.

Overnight,

almost, it turned itself over to the anti-cuts movement, with flyers,

listings, e-petitions, links. And Power herself seemed to lose interest

in vintage feminism, writing instead about kettling and hyperkettling

and the brain injuries sustained—after last year’s anti-tuition-fees

demo in London—by the philosophy student Alfie Meadows. “Lecturers,

Defend Your Students!” she bolshily entitled her contribution to a

collection called Springtime: The New Student Rebellions. It

must be relevant that the first university department to close as a

result of government cuts was philosophy at Middlesex, where both Power

and Meadows studied.

And as if on cue, James and her comrades

were out in force this June at the first London SlutWalk, given that

name after a police officer in Toronto suggested that if girls didn’t

want to be raped of an evening, they “should avoid dressing like sluts.”

So obviously lots of people— not just women—wanted to dress up as sluts

to point out the absurdity of this position; and lots of people, like

me, wanted to march in solidarity, wearing our usual boring clothes. A

little girl marched in a fairy costume. A transgender couple marched in

matching wigs, hiking sandals, gigantic inflatable penises. WHAT WERE

WOMEN WEARING IN LIBYA, CONGO, DARFUR WHEN THEY WERE RAPED? read one

placard; WE ARE ALL CHAMBERMAIDS, said another, with a little picture of

Dominique Strauss-Kahn; Selma James had a home-made sign with PENSIONER

SLUT on it, and a little heart.

A couple more items from the

scrapbook. International Women’s Day this March was marked by the

broadcaster Mariella Frostrup with a piece in the Observer about her new

charity, the ingeniously acronymical Gender Rights and Equality Action

Trust, aka Great. The Great website has a big picture of Mariella, wan

and elegant in a row of smiling African women refugees: “From Mozambique

to Chad, South Africa and Liberia, Sierra Leone to Burkina Faso,

feminism is the buzzword for a generation of women.” In May they had a

big charity auction in a “new ultra-luxury hotel” with “the most

exclusive guest list” and “an unforgettable performance from Mark

Knopfler.” No wonder those refugee ladies are grinning from ear to ear.

Also on International Women’s Day, Power wrote in the Guardian about “Rage of the Girl Rioters,” the title of a Daily Mail piece

about the anti-tuition-fees day of action last November. She saw

the Mail’s treatment as ‘the latest in a long line of attacks on women

who campaign directly against the state’, such as suffragettes and rent

strikers and bra-burners, miners’ wives and 1990s ladettes. “What looks

to be a moral criticism,” she writes, “frequently masks a deeper

political and economic fear—what shall we do when young women are

academically successful, economically independent, socially confident

and not afraid to enjoy themselves? Could there be anything more

terrifying?”

Rage of the Girl Rioters! I thought as I was reading. This I have to see! So I looked at the Mail’s website, and found some interestingly dialectical comments under the piece. “I don’t appreciate my daughter’s picture being [in this section] . . . She was actually coming out from a crowd rush after nearly fainting!” writes a lady from West London. “In your typically misogynistic attempt at smearing these protesters,” says a young man from Kuala Lumpur, “I have to hand it to you. This must be one of the coolest collections of photos I’ve seen from the day.” Not so long ago, it was impossible to imagine young women, young people, or anyone really, protesting in numbers about anything; now, they’re on the streets and furious all the time. The Daily Mail, concluding its analysis: “Thus, for the first time in a protest filled with confrontation and hatred, young girls took centre stage. Now everything is up in the air and changing all the time.”

Among the recent books consulted in the writing of this piece: The Equality Illusion: The Truth about Men & Women Today by Kat Banyard (Faber, 2010)

Dead End Feminism by Elizabeth Badinter (Polity, 2006)

Feminism Seduced: How Global Elites Use Women’s Labour and Ideas to Exploit the World by Hester Eisenstein (Paradigm, 2009)

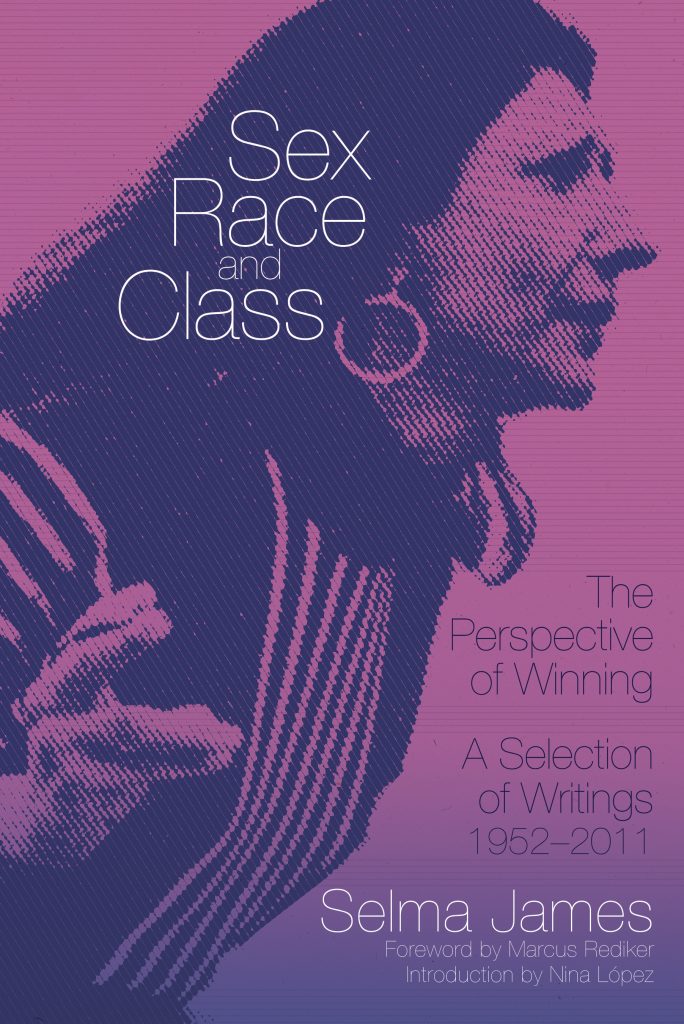

Sex, Race and Class: The Perspective of Winning: A Selection of Writings, 1952-2011 by Selma James (PM Press, 2012)

Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture by Ariel Levy (Free Press, 2005)

How to Be a Woman by Caitlin Moran (Ebury, 2011)

Meat Market: Female Flesh under Capitalism by Laurie Penny(Zero, 2011)

One Dimensional Woman by Nina Power (Zero, 2009)

Reclaiming the F Word: The New Feminist Movement by Catherine Redfern and Kristin Aune (Zed, 2010)

Dreamers of a New Day by Sheila Rowbotham (Verso, 2010)

Letters 34, no. 1

January 5, 2012

I

think that Jenny Turner and I want the same thing: a revolutionary

feminism committed to overcoming the family, transforming economic life

and providing people with better choices than the ones currently offered

them (LRB, December 15, 2011). It is rare to see someone want these

things in writing, in public, in a mainstream publication. So why was

her essay so hard for me to like? Mostly, it is that Turner wants to use

historical analysis to figure out what the future will be like, and her

history is garbled and wrong.

For example, she points out that

Elizabeth Cady Stanton opposed suffrage for freedmen in the years

following the Civil War. Stanton, along with many other first-wave

American feminists, was an abolitionist first. Abolitionism taught them

organisation, political tactics and rhetorical fire, and they spent

decades giving speeches, circulating pamphlets, and being called ‘nigger

lovers’ as they walked down the street. It was only after the Civil

War, with abolition completely achieved, that Stanton and other

feminists lodged their opposition to the 14th and 15th Amendments. The

reason is they expected a little reciprocity from the cause to which

they had devoted so many years, and got none; those Amendments let

male-only suffrage go unchallenged. It is perfectly legitimate to

criticise Stanton’s decision to oppose these amendments, but it is

contemptuous to imply that it was made on the basis of nothing more than

self-absorption.

“Who . . . ever heard of a radical-feminist

movement taking its understanding of historical change from a man?”

Turner asks. Well, everybody, actually. Shulamith Firestone wrote that

Freud ‘grasped the crucial problem of modern life’. There was also Marx,

who radical feminists discussed (and still discuss) all the time. She

claims that consciousness-raising was invented by lesbian separatists,

women who wanted to ‘build a man-free, women-only tradition’ of their

own. This is completely backwards. Radical feminists of all kinds

invented consciousness-raising because they felt domestic life had

isolated women from one another, and that it might be useful to have a

little space to work out ideas together. The lesbian separatism came

later.

These details matter, especially in an essay that gives

the impression of a strange contempt for feminism in general. Whenever

Turner finds an event, or a protest, or an idea that she likes, it is

usually some exceptional individual woman who is behind it. Whenever she

disapproves of something, then “feminism,” or “Women’s Liberation,” or

“libbers,” or the “radical-feminist movement” is to blame. I sympathise

with almost everything that Turner wants for feminism’s future, and I

agree with her that certain strains of feminist thought have been

misguided and counterproductive. But she also seems to want to do

without any kind of movement at all, or at least to forget about any

movement that preceded her writing her essay.

Richard Beck

Brooklyn, New York

Jenny

Turner is disappointed in Western feminism for too often wanting to

have its cake (by adopting a critical stance towards whatever seems to

hinder women from having the lives they want, or ought to want) and eat

it (by declining to challenge the economic and familial structures

within which these hindrances come about). But Turner’s own attempt at a

radical challenge to the world as it is does not inspire confidence.

She quotes with approval Toni Morrison’s claim that the nuclear family

“just doesn’t work”—it causes narcissism, consumerism, overeating,

undereating and self-harm, according to Turner—and applauds Morrison’s

vision of a world in which a teenage single mother who aspires to train

as a brain surgeon can readily do so, thanks to fellow community

members’ willingness to take care of her baby for free. Turner assures

us that the rightness of this line of thought is ‘obvious’ once you come

to think about it; presumably this is why she presents no evidence to

support the correctness of the diagnosis, much less the viability of the

solution.

Michael Nabavian

London N5

In her piece on

feminism, Jenny Turner incidentally misrepresents the motives behind the

closure of Middlesex University’s Centre for Research in Modern

European Philosophy, now transferred to Kingston University (LRB, 15

December 2011). Government cuts did not lie behind the decision. Rather,

philosophy did not fit with Middlesex’s international strategy and the

university knew that by closing the centre, it could keep the money

awarded for its strong research performance in 2008 and use it for

something else. The Higher Education Funding Council for England will

continue to give Middlesex something in the region of £175,000 per year

until the results of the next national assessment of university research

are known—sometime around 2015-16—even though most of the staff who

generated that income are now at Kingston. Middlesex closed its highest

rated research unit in order to take a profit on it.

Andrew McGettigan

London N1

Letters 34, no. 2

January 26, 2012

Jenny

Turner’s “scrapbook” on feminism begins and ends with girl rioters’

“flat-out joy” and what might be called shopping situationism (LRB,

December 15, 2011). The young women who joined last summer’s riots are,

she tells us, “the problem with feminism.” But what is this problem?

Young women “losing their heads” or feminists who didn’t?

Yes,

the riots were a problem: the medium—collective larceny and incendiary

violence— obscured the inaugural message, that a black man, Mark Duggan,

had been shot to death by the Metropolitan Police. The riots exposed a

crisis of politics: a cruel gap between the cause and consequences of

Duggan’s death. That crisis is those girls’ tragedy; it is our tragedy.

Why doesn’t Turner address this? What has feminism done to deserve her

rant?

One soul is exempt from Jenny Turner’s splatter critique:

Selma James. Those of us who belong to the Women’s Liberation generation

remember well James’s Wages for Housework campaign. Jenny Turner is

right about one thing: James was never popular. Her virtuoso

sectarianism was not attractive, and her leftist populism named an

important issue (unpaid domestic labour) without challenging the power

structure that produced it.

The Women’s Liberation movement didn’t adopt Wages for Housework because

it didn’t challenge the patriarchal political economy, or the domestic

division of labour, or men. Far from being an “intellectually ambitious

attempt to synthesise Marxism, feminism and postcolonialism,” its theory

was crude and its practice toxic.

However, a host of women

certainly did undertake ‘intellectually ambitious’ work. Juliet

Mitchell’s essay, ‘Women: The Longest Revolution’, published in 1966

in New Left Review, a pioneering analysis of the lacunae in Marxism

(relations of social reproduction and the sexual division of labour),

was a founding text of British feminism. Women’s Liberation was animated

by a torrent of intellectual endeavour and awareness-raising (derided

by Turner as sitting around but really another term for thinking). This

didn’t impinge much on Wages for Housework, or on Turner either. She

finds alluring a slogan most of us thought was bonkers.

Turner

burdens feminism with both too little and too much power when she asks

how it has ‘drifted so far out of touch’. After the 1970s Women’s

Liberation lived on not as a thing, a place, an address – it had no

institutional moorings – but as contingent politics: as ideas, as

coalitions, as challenges in the professions, political parties and the

academy, in women’s services, and in popular culture; it created new

political terrain. All this is ignored by Turner, who relies on an

American leftist critique that feminism has narrowed its focus from a

politics of redistribution to recognition (identity) politics:

recognition can be accommodated, redistribution cannot. It claims that

feminism thrives in neo-liberalism. It does not thrive. Remarkably,

however, it survives. There’s a difference.

The conditions for it

to flourish were eroded by the rise and rise of what Stuart Hall calls

Thatcherism’s ‘regressive modernisation’, the assault on state

welfarism, the neoliberal sway of the global economy, and an ideological

offensive in which it is right on to be right off.

Feminist

activism in these islands exemplifies not the collapse of either

recognition or redistribution but—in the most dispiriting conditions –

their necessary synergy. Feminism is still breathing here, there and

everywhere. It audits the cost/ value of the domestic division of labour

as a form of redistribution from women to men, and its acute

manifestation, for example, in the coalition’s budget strategy. The

Women’s Budget Group last year amplified Yvette Cooper’s calculations on

the coalition’s deficit reduction strategy: 72 percent of the cost of

the budget was borne by women. This evidence ignited a legal challenge

by the Fawcett Society on the grounds that the budget strategy

transgressed statutory equality duties.

Turner is distracted,

however, by ‘a harsher divide’ between the privileged 13 percent of

women who earn “just as much as men” and the rest. “Feminism

overwhelmingly was and is a movement of that 13 percent”—the prissy,

“let-them-eat-cakey” monstrous middle-class regiment of women. Class

discombobulates Turner. Would anyone in their right mind malign Angela

Davis or Stuart Hall because they’re black and middle-class? Middle and

working cultures have always been mobile, moving in and out of each

other. Politics is where we can in engage in “becoming” rather than

“being,” not as identity politics but as a way—and this is the point,

after all—to overcome the subjective and social injuries of

subordination.

Strange, says Turner, how often feminism hasn’t

engaged with race and class. Strange, I say, that she hasn’t registered

the intensity of these engagements. Cue her allusion to the white

American abolitionist and suffrage campaigner Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Turner says she ‘opposed votes’ for black freedmen. No, not quite: she

insisted on votes for black men, and women black and white, at the same

time. It split the suffrage movement. The great Sojourner Truth, born

into slavery, had sympathy for this argument. She told the American

Equal Rights Convention in 1867 that ‘man is so selfish that he has got

women’s rights and his own too . . . he keeps them all to himself.’

Multiple oppressions and modalities of power have always –

inevitably—circulated in feminist politics.

This brings us to

Turner’s larger problem: politics itself. She gets all roused up over

the wrong question. Why did a book catalyse feminism, she asks. Being a

book, it “only works for middle-class women.” So, working-class women

don’t read? Actually, Women’s Liberation bounced out of activism not

texts: the detonator was black and white women’s humiliation within the

liberation movements of the 1950s and 1960s: the Freedom Rides, the

Civil Rights and anti-war movements. The American Women’s Liberation

movement was born out of resistance to racism, war and male chauvinism,

in that order. These histories are withheld from Jenny Turner’s

undignified tantrum. We learn that she is angry—but she is angry with

the wrong people.

Beatrix Campbell

London NW1