By Becky Gardiner

Guardian UK

June 8, 2012

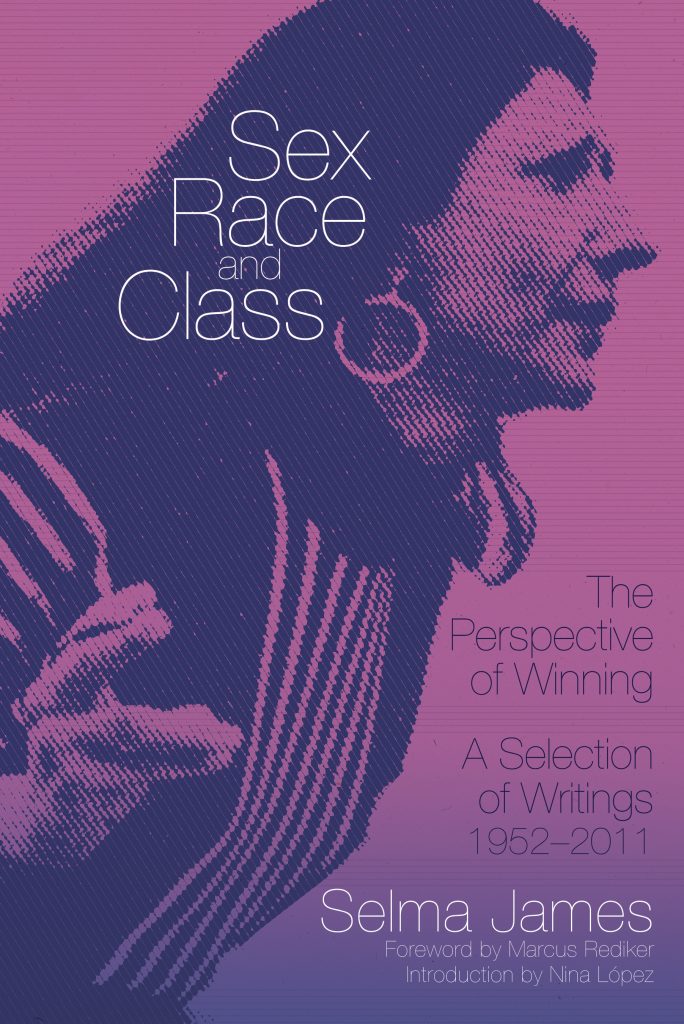

“By demanding payment for housework we attack what is terrible about caring in our capitalist society”

Selma James describes the frustrations of women’s lives.

Photograph: Eamonn McCabe for the Guardian

The last time Selma James was interviewed by the Guardian was in 1976, by the feminist columnist Jill Tweedie. At that time, James was a household name—in feminist households at least—and this is how Tweedie began: “To many women in the women’s movement, the Wages for Housework campaigners come over like Jehovah’s Witnesses . . . Selma James and her sister enthusiasts . . . harangue conferences, shout from soapboxes, gesticulate on television, burn with a strange fever . . . On the street corner they go down well. Within the movement … they set up a high level of irritation. Eyes roll heavenwards, figures slump in seats as yet another campaigner leaps for the platform.”

Many years have passed, and James has long since been dismissed by many of her feminist contemporaries as an irrelevant, or even ridiculous, figure. Her work has been neglected; her key demand—wages for housework—written off. And yet James herself has neither stopped, nor slowed down for a moment. When we meet, she is fresh from a trip to the United States. There to promote the new anthology of her writing, she became embroiled in a row that rocked the presidential race. One of Obama’s team said Mitt Romney’s wife Ann, a mother of five, had “never worked a day in her life,” and in a flash, there was James, gesticulating on television again (the Amy Goodman show this time), explaining, yet again, about the significance of women’s unwaged labour in the home. The gleam is still in her eye, she still burns with a strange fever. She is eighty-two.

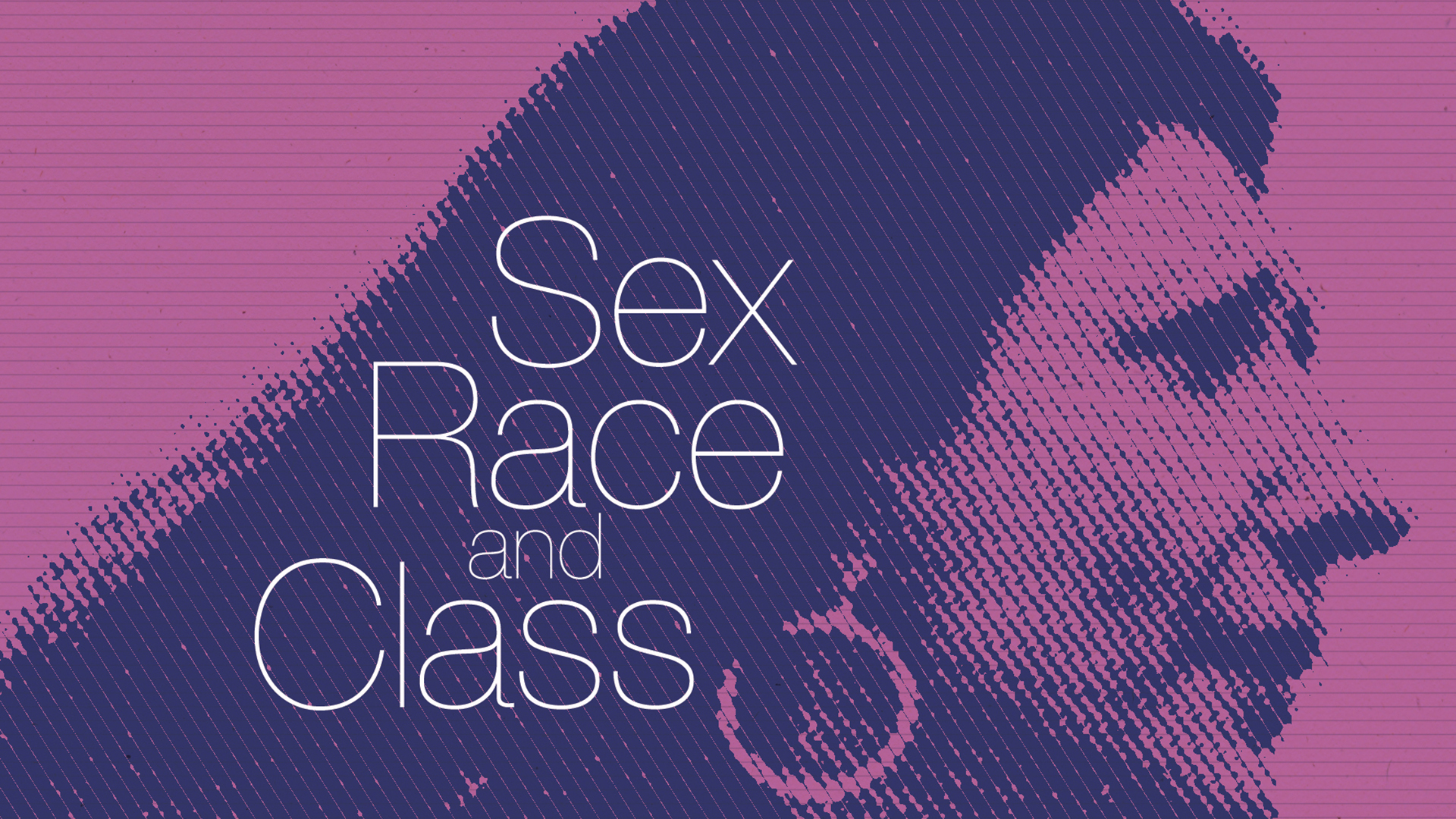

The anthology, Sex Race and Class (Merlin) is a collection of speeches, articles—mainly from now defunct leftist newspapers—and essays originally published as campaigning pamphlets.

Every piece is rooted not in academic study but in activism: a campaign to defend family allowance (1973); an occupation of a church to defend prostitutes against the police (1983); a speech about Jewish anti-Zionism (2010); an account of her work with death row prisoner and “jailhouse lawyer” Mumia Abu-Jamal (2011). In the first essay, “A Woman’s Place,” James describes the frustrations of women’s lives as housewives, mothers and workers, and ends with the words: “Things can’t go on the way they are. Every woman knows that.” Written in 1952, it is a prescient piece of work.

Her campaigning and her writing—the two are indivisible—spring from one central insight: that “housework” (not just vacuuming, but all the work involved in meeting the physical and emotional needs of others, from cradle to grave) is central to the reproduction of humanity, and therefore to capitalism. By focusing on the unwaged, Wages for Housework revolutionises our idea of what work is, and who the working class are. It allows us to see the potential collective power of those who are most isolated and seem powerless: women stuck at home changing nappies. And it goes straight to the heart of a dilemma that still plagues many women: “I started,” James says now, “as a housewife refusing housework. As a mother, doing this work that is so central to society, I was locked in and impoverished. But this work is not like other work: we hate it, and we want to do it. By demanding payment for housework we attack what is terrible about caring in our capitalist society, while protecting what is great about it, and what it could be. We refuse housework, because we think everyone should be doing it.”

She was born Selma Deitch in Brooklyn in 1930. Hers was one of four working-class Jewish families who lived in a house on the corner of Ralph Avenue and Dean Street, where the Jewish ghetto met the black ghetto: “Our front door faced on to the black street, but our address was on the white street. By the time I was six I understood a lot about racism. I could smell it in the people I knew.” From day one, anti-racism was central to James’s feminism. So, too, was the left. “The movement was everywhere,” she remembers. Her truck-driver father was a trade unionist when that meant beatings from the mafia and regular spells in jail, her mother a housewife who struggled to make ends meet and battled for justice for the welfare mothers on her street. Aged six, James was combing the streets with her sisters, collecting foil cigarette wrappers for the Spanish Republicans: “We’d roll them into these huge bullets. What they used them for, I don’t know.”

When she was still a girl, James joined a splinter group of the Workers party (WP) called the Johnson Forest Tendency. The group’s leader was the Trinidadian historian and anti-colonialist, CLR James. It was a tiny group, at war with the WP leadership. At its height, there were only 70 Johnsonites: “Seventy people scattered across a big country—not a lot. But the leader was a black man, an immigrant from the West Indies and a historian; his two closest colleagues were women, one a Russian immigrant, the other first-generation Chinese-American . . . We were multiracial. We were confident. We felt we were ‘going somewhere’ . . . building not a vanguard party so we could one day be the state, but a movement.”

James started attending CLR’s classes in slavery and the civil war and he noticed her: “He said to my sister: ‘When I mention the dialectic, your sister’s eyes light up.'” She was fourteen when they first met; he was forty-four. It was CLR who persuaded her to write, to speak up. “He shaped my mind. But it was the mind I wanted. I always wanted to know how to think, and there was this man who knew.”

At seventeen, she married a fellow factory worker; by eighteen she’d given birth to their son, Sam. The marriage, she says, was over before it began, and they eventually separated four years later.

By then,

McCarthyism was in full swing: “phones tapped, mail interfered with,

visits from the FBI. Some of us lost our jobs (I lost mine), some were

blacklisted.” CLR James was sent to Ellis Island, where Selma wrote to

him regularly; slowly, they fell in love. On his release, and fearing

deportation, CLR left for London. Selma and her son went with him and

shortly afterwards, they married. What was it like, being in a

mixed-race marriage then? Finding a flat was difficult, she admits, but

London in the mid-50s was not as racist as it later became:

“You’d see mixed marriages all the time. Working-class people found their way to each other, and there was not a problem.”

They were together for almost thirty years. Ostensibly, he was the intellectual, she his audiotypist (she typed Beyond a Boundary so many times, she says, that she could recite the entire book from memory) but she always held her own. Journalist and activist Darcus Howe, CLR James’s nephew, remembers “this tiny white woman” working alongside black people, and “always asking so many profound and serious questions.” She was formidable, he says: “That finger-pointing, those eyes flashing!” Was he intimidated? “Oh, no. I liked her very much.”

In 1958 James went with CLR to Trinidad, where he edited the pro-independence party’s newspaper. She fell in love with the West Indies. “What the people did with the language was Shakespearean! They opened the language, transformed it.” Even now, her Brooklyn accent is softened by a West Indian lilt, as if she absorbed the essence of the place. But she was not impressed by those who led the independence movement: “I saw the state close up. It was an enormous education. Almost all of them were awful. It is the ambition, it makes people awful.” By the time she left, she had “had enough of the middle class, of the intelligentsia. I thought, I am going to be with working-class people from now on.”

She arrived back in London in 1969, just as the women’s liberation movement invented itself.

The British feminist, Bea Campbell—no friend of James—remembers it as “a torrid, marvellous time, with groups being formed suddenly, and everywhere.” Campbell was twenty-two, and recalls a movement as “full of women in their 20s”. Enter James: “She was forty, fully-formed, fortified,” says Campbell. “She knew how to do battle. A small Trotskyist sect formed her, and she has remained schismatic ever since. Schismatic, sectarian, polarising: Selma got on women’s nerves.”

That’s not how James remembers it. The schism was not about age, she insists, but class: “I brought a reality to the movement they didn’t want to acknowledge: that there is a struggle going on, and we have to decide whose side we’re on.” And all that talk of liberation through work! James had spent years working a double day in a factory and as a housewife: she knew what working-class women felt about factory work: “They walk in, they run out.” Too many women in the movement simply “didn’t know anything about the world”.

And it was about race, too. James was living “a double life” at that time. Her best friends were not white feminists, but the West Indian nurses she knew though her anti-racist activism.

Selma remembers the time her great friend, Earla Campbell met Juliet Mitchell, the eminent feminist psychologist: “It was one of these early women’s liberation demos, and I took Earla along. Afterwards, she said to me: ‘Do you know how much Juliet’s shoes cost? Fifteen pounds!’ Earla was making £15 a week. She said, what are you doing with these people?”

James is on a roll now, finger pointing, eyes flashing: “When Michael [Rabiger, a BBC producer] asked me to make a film about the women’s movement, Juliet Mitchell was horrified. She said to him: ‘Not Selma! She’ll make a film about black power!’ The idea that, because I was part of the black movement, I could not at the same time have as my focus women is beyond belief stupid. But that’s who [the leading 70s feminists] were. They objected to me because I was standing in the way of what they wanted their political direction to be.”

The 70s was a productive period for James, albeit one punctuated by fighting. A collaboration with the Italian feminist, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, produced The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community in 1972, published first under Dalla Costa’s name alone, but claimed by James in the anthology as a joint work. The two later fell out, for reasons that are unclear. The same year James wrote Women, the Unions and Work, Or . . . What Is Not to Be Done. This pamphlet, written in four hours, Xeroxed, and distributed on the coach up to the 1972 Women’s Liberation conference, contains six demands, beginning with “We demand the right to work less,” and including, for the first time, “We demand wages for housework.”

Many women were hostile. “One woman asked, will it institutionalise women in the home? I said, I don’t know. It hadn’t crossed my mind. But I said to myself: ‘Maybe it will. Wouldn’t that be wonderful!’ I thought, if it did, I could stop typing and listen to my music! Some said women must go out to work to raise their consciousness. But others said: ‘No, my mother’s been out working for twenty years and she wants to come home.’ And I said, this is it! This is Wages for Housework.”

These arguments are rehearsed by Tweedie in her 1976 Guardian article, in which she questions, with great honesty, her own irritable reaction to Wages for Housework. “What do I feel?” Tweedie asks: “The horrid resentment of the mind bred to slavery and faced with freedom.”

In the wider women’s movement, though, James lost the argument. Women coalesced around other demands, the first of which was “equal pay for equal work.” Middle-class women began to enter male professions. A wrong turn, according to James: “Every time we build a movement a few people get jobs, and those who can get the jobs claim this was the objective of the movement.”

James, meanwhile, spent the first few years of the ’70s living on grants, benefits and typing, and talking about Wages for Housework: “Increasingly I found out what Wages for Housework was.” It was not simply a demand at all, but “a political perspective, a class perspective that began with the unwaged rather than the waged. There was no section of the working class that was left out of this perspective, neither in the third world nor in the industrial world. I thought: look what was in it! I never knew! By 1975 the debate was over for us; it was time to put the perspective into practice.”

Her Crossroads Women’s Centre began as a squat in a red-light area near Euston station in 1975; in May this year it moved to smart new premises. In the years between they have faced eviction several times, but the centre was always saved—on one occasion by squatters, including Bengali families, who had received support from the women there. It is, as far as James knows, the oldest surviving women’s centre in London, if not the UK, and it is currently home to more than fifteen groups, including the English Collective of Prostitutes, Legal Action for Women, Women Against Rape and—naturally—the International Wages for Housework Campaign. Links have been made with domestic workers in Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, rural women in India and Uganda, and sex workers in the Philippines.

There have been struggles, and triumphs, some of which are documented in Sex, Race and Class. “The UN Decade for Women — An Offer We Couldn’t Refuse” tells the story of a painstaking ten-year struggle to force the UN to recognise women’s unpaid work. “Hookers in the House of Lords”, an account of a prostitutes’ occupation of a church in 1982, is a hoot, and has clear parallels with contemporary occupations: “We were very sorry to leave . . . We were physically exhausted and we craved a bath and bed. Yet we were loath to re-enter the flat atmosphere of daily life. In masks [worn by the occupiers to protect the prostitute women’s anonymity] we had glimpsed what could happen: we created change. Taking off the masks, our collective power was as hidden as the reality it had penetrated . . . It was hard to remember we had won.”

A new generation of feminists is discovering James’s work. Academic Nina Power and writer and blogger Laurie Penny, for example, both cite her as an influence. In a recent article in the London Review of Books, Jenny Turner launched a serious reappraisal of James’s campaign.

Meanwhile, James’s call for a guaranteed income, her insistence that a post-work world might be possible, finds echoes in contemporary movements, from Occupy to the Pirates party. None of this is lost on James. The Occupy movement delights her, and she was an enthusiastic participant in last year’s feminist Slutwalk, where she strung a placard around her neck with the words “Pensioner Slut” scrawled above a little red heart.

Today she seems happy. She lives with her fellow campaigner and partner of nineteen years, Nina Lopez, in a modest flat in London. A bronze head of CLR James looks down from the mantelpiece, surrounded by photos of James, Nina and their collie dogs. Her son, Sam Weinstein, is a radical trade unionist in America, and she is fiercely proud of him. She remains actively involved in the Crossroads Women’s Centre and is busy, always. The movement, as she would say, is everywhere.

The final essay in Sex, Race and Class is called “Striving for Clarity and Influence.” It is a fierce defence of CLR James’s political legacy against those who would see his achievements in purely literary terms. In it she writes: “Politics, if it is fuelled by a great will to change the world, rather than by personal ambition, offers a chance to know the world, and to be more self-conscious of the actual life you are living rather than being taken over by what you are told you should feel: a chance to live, in other words, an authentic life. Such politics are a unique enrichment, not a sacrifice.”

For anyone interested in CLR James, the essay is fascinating. But when I read it, I think of Selma.