By Belinda Webb

The Tribune Magazine

June 2011

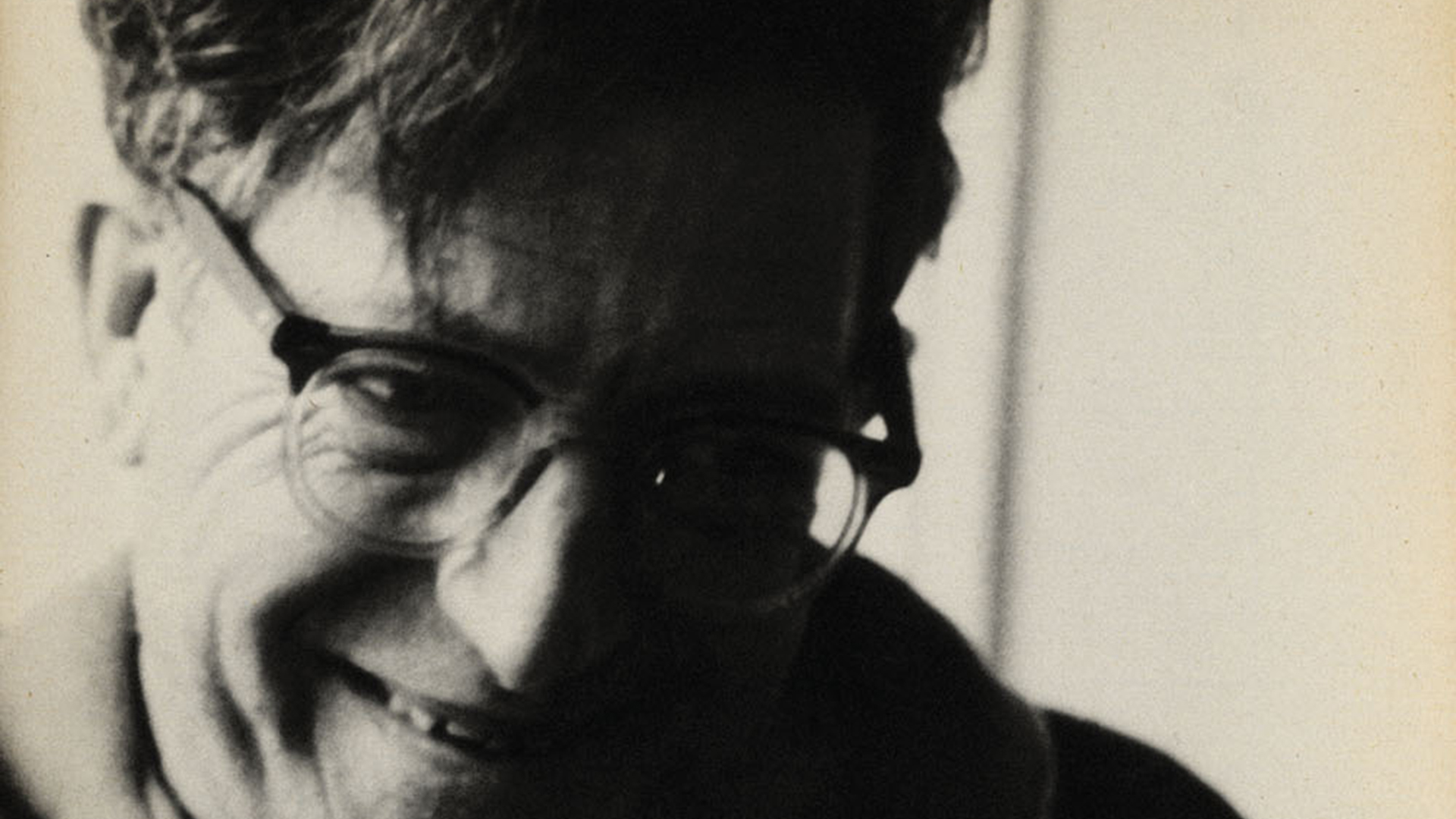

No, this isn’t a review of a reader on the works of the Conservative politician Paul Goodman (heaven forfend), but of the American writer and social critic who inspired the youth movement throughout the 1960s: a holistic, pacifist, anarchist man of letters, as he would label himself.

“Pacifist anarchist” may seem like an oxymoron, but Goodman was fervently anti-violent; passive resistance, like that espoused by Gandhi, was key. It may surprise some that Goodman was also one of the co-founders of gestalt therapy, the phenomenological existential therapy created by Fritz and Laura Perls in the 1940s. The goal of a phenomenological method is awareness of what’s happening in the here and now, not an interpretation and re-jigging of existing attitudes. You could almost imagine Karl Marx taking to it with gusto because the aim is not to interpret, but to change. It was the attitude that Goodman brought to all his many and diverse writings, and one which won him admirers like Susan Sontag, for whom he was a hero, although she felt he held her in disdain.

I found his work a revelation. I was aided in this by a

thorough, generous and warm introduction by Taylor Stoehr, whose

overview serves to remind older readers and inspire new ones now eagerly

supping up the eloquent articulation of constraints that are even more

relevant in these troubled Tory times. The Reader is well organised,

although there is an irony in it being so well categorised—politics,

literature, psychology, theology and so forth—considering that Goodman’s

holistic approach seemed to rebuke such categorical distinctions. There

is a good selection of his poetry here, too, although I was

disappointed not to find his essay On Being A Writer. Maybe it was

because it wasn’t his fiction or poetry that secured his recognition but

his social criticism.

Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organised Society

(1960) ignited the fame that would be his until his death in 1972 at

the age of 60. The book “launched a wide-ranging critique of American

society and its failure to make a world worthy of earnest and idealistic

young people.” In this critique he was not alone. In the late 1950s and

throughout the 1960s, there emerged works by those such as William

Whyte, author of The Organization Man (1956), which claimed

that a cautious collectivist ethic had usurped the rugged individualism

upon which America was founded. There was also The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,

the 1955 novel by Sloan Wilson, which, along with Whyte’s observations,

seemed to confirm the visions which fed novels like Richard Yates’ Revolutionary Road,

in which wage slavery and worshipping at the altar of the corporation

while commuting in mind-numbed drones were treated with the contempt

they deserve. Like Yates, Goodman maintained that his ideas were

“implicit in the Jeffersonian radical democracy upon which the U.S. was

founded.” It is a problem that still afflicts our societies—the problem,

as Goodman put it, of autonomy.

Unlike most social critics, Goodman despised abstract thought, such as freedom as a metaphysical concept. Instead, he saw freedom as being a “deep animal cry” and, therefore, intrinsic to who and what we are. No wonder, then, that he referred to Marx as a social psychologist, with his illuminating sketches of human alienation and disaffection which Goodman expanded on. You could easily assume he was inspired by Marx, but Goodman said he only found retrospectively that everything he wrote was in agreement with Marx so he thought he, too, must be Marxist, although he would later become critical of the ideological harshness of the New Left. Goodman was gentler, more compassionate, and his work remains fresh and personable. This Reader presents a man deeply committed to humans being free and, more importantly, feeling free—a work in progress that this generation must make their priority.

Back to Paul Goodman’s Author Page | Back to Taylor Stoehr’s Editor Page