Simulation Liberation Army

By M.W. Lipschitz

Los Angeles Review of Books

June 13th, 2017

FILM CRITIC Parker Tyler described the modern movie myth as a “pattern capable of many variations and distortions, many betrayals and disguises, even though it remains imaginative truth.” This definition could extend to media narratives, and the bizarre 1974 kidnapping of Patty Hearst certainly registers as a prime example.

Hearst’s seizure at the hands of the self-styled revolutionary, bank-robbing Symbionese Liberation Army has been the subject of three books in the last three years, and of them, American Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trial of Patty Hearst, Jeffrey Toobin’s account has garnered the most attention, though it hews closely to the established narrative. It’s been advertised as the “definitive account.”

Brad Schreiber’s little-known Revolution’s End: The Patty Hearst Kidnapping, Mind Control, and the Secret History of Donald DeFreeze and the SLA tells a counternarrative of the SLA as the product of an extensive counterintelligence program that spiraled out of control. Printed by a small press, Revolution’s End substantiates its story with police records and investigative journalism from the period.

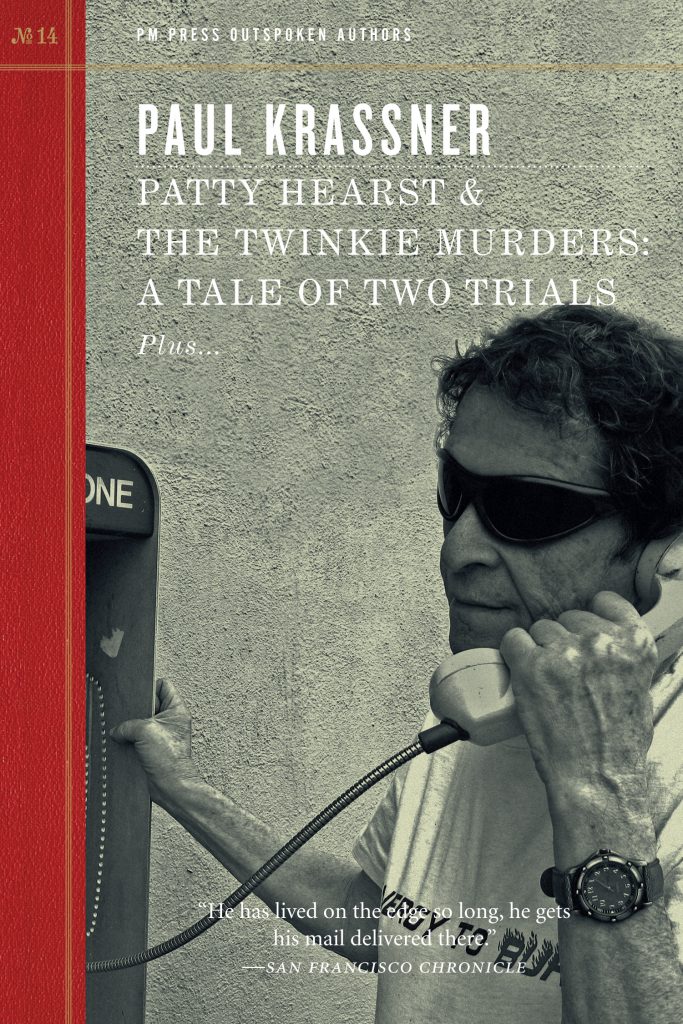

And then there is Patty Hearst & the Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials, by Paul Krassner, a satirist whose first-person account is all the more insightful for being untethered from the objective of being “definitive.” Together, these books present a divergent mosaic of opinions and fact-patterns on the kidnappers that evades easy definition even four decades later.

In the accepted narrative, Patty Hearst is the queen of missing white girls, a symbol of the disproportionate flooding of the media with coverage of Caucasian kidnapping victims. Hearst’s message also personifies a deep fear in the United States: the black stud defrocking the lily flower. Toobin’s perspective affirms the narrative of the destruction of political overlap between middle-class college students and the Black Power Movement, which made up two pillars of the left. By 1974, the momentum for social change had been divided and conquered by infighting, infiltration, and, finally, Nixon’s draconian law-and-order sales pitch. Krassner, says it best: “Patty had become a vehicle for repressive action on the right and for wishful thinking on the left.”

The word Symbionese — a portmanteau combining the “Vietnamese” War with the William Greaves’s film Symbiopsychotaxiplasm (1968), or perhaps Sam Greenlee’s use of “racial cross-section symbiology” in his novel The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1969) — remains almost as inscrutable as the “happenings” surrounding its creators. Herewith, a brief chronology:

• March 5, 1973: Donald DeFreeze escapes from Soledad State Prison and lands in Berkeley.

• November 6, 1973: DeFreeze, Nancy Ling Perry, and Patricia Soltysik shoot and kill Oakland Schools Superintendent Marcus Foster, an African American education reformer and community leader.

• February 4, 1974: a small band of white men and women led by DeFreeze kidnap the 19-year-old granddaughter of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst.

A suspicious shadow persists beneath any simplistic explanation. The SLA communicated via audio-taped communiqués. Their ransom demands forced Patty’s father Randolph Hearst to orchestrate a Food Give Away in California costing him millions. Then, in proto–Stockholm Syndrome fashion, Patty joined her abductor’s struggle. It shocked the country to hear her faint voice proclaim: “Death to the Fascist insect that preys upon the blood of the people.” The self-proclaimed urban guerillas staged a now-iconic photo of Patty with an M-1 assault rifle slung around her shoulder in front of the seven-headed SLA cobra icon, one of the enduring American images from the 1970s.

The SLA mimicked liberation struggles, using code names and didactic symbolism. DeFreeze became General Field Marshal Cinque — in one move a kitschy rebuke of the Black Panther hierarchy and a shedding of his “slave name.” The other members — Nancy Ling Perry (Fahziah), Camilla Hall (Gabi), Patricia “Mizmoon” Soltysik (Zoya), Russell Little (Osceola), Joseph Remiro (Bo), Willie Wolfe (Cujo), Angela Atwood (General Gelina), Emily Harris (Yolanda), Bill Harris (General Teko), and Patty Hearst herself (Tania) — were, to the square community, a witch’s brew of feminism, lesbianism, Marxism, black liberation, anticolonialism, free love, and an antiwar hatred of “pigs.”

The story sounds familiar because, in each ensuing generation, the Patty Hearst Myth has been reborn, to warn the United States of the risk in repeating the “days of rage” and protest of the late ’60s and early ’70s, a period when the American system feared for its own survival.

Documentaries like Guerrilla: The Taking of Patty Hearst (2005) play it safe. Paul Schrader’s film Patty Hearst (1988) stars Ving Rhames as Cinque, but it’s unwatchable. The porno Tanya (1976) — “What, you never seen a black cock before?” — is one of many smut adaptations.

In depictions of political radicalism, the SLA lives on as the go-to model — see Network (1976), 12 Monkeys (1997), and The East (2013). Even Woody Allen’s stale Crisis in Six Scenes (2016) serializes Miley Cyrus as a Patty Hearst surrogate spouting pidgin Marxism as a member of the “Constitutional Liberation Army.” In simulating a suspect simulation, Allen lowers the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground to the same moral level as the SLA. In sum, what has been lost in the afterlife of the SLA is the meaning of the SLA.

Toobin opines that the SLA “illuminated the future of the media,” adding that Hearst’s kidnapping was an “anomalous event […] the story of a single young woman.” He stakes a flag in historical territory that is much larger than he realizes.

In 1974, the United States was in the grip of oil embargos, Watergate, Vietnam ending (sort of), big city crime, and Hollywood New Wave cinema. The Establishment had launched its assault on the Movement that they believed was tearing apart the country. Toobin’s territory leads to a salient question: did Patty join her captors’ crusade out of free will or through coercive brainwashing? However, if you imagine the SLA story without Patty Hearst, you begin to see it isn’t only about her. Lost in this narrative is the SLA’s assassination of Oakland School Superintendent Marcus Foster, the heinous act that launched their wild spree. When investigated, killing Foster makes little sense. Black Panther Chairman Huey Newton publically denounced Foster’s slaying, which landed Huey on the SLA’s “deathlist.”

With poise, Schreiber relegates Hearst to the sidelines (as much as he can) and focuses on Donald DeFreeze, the enigmatic-pawn-cum-rogue-leader of the SLA. Schreiber connects activities in the LAPD, FBI, and CIA to prisoner programs within the California Department of Corrections, leading to then-Governor Ronald Reagan’s cabinet, and UC Berkeley. Within the rubric of alt-history, this is fruitful territory.

Most book critics, seemingly unaware of the contested history of the SLA, have given American Heiress a pass in this regard. Toobin was refused an interview with Patty Hearst, and so he must take her own memoir, Every Secret Thing (1981), as one of his main sources, mixing it with the diaries of other SLA members and, at its most lively, the absurdist courtroom drama. But the hypocrisy and skepticism of 1974 isn’t there. In Toobin’s “selected bibliography,” there is a missing link where nearly every other book written about the SLA is listed: Paul Krassner’s account is conspicuously absent.

Krassner was a creature of the once-vibrant alternative mediasphere. A member of the Yippies, confidant of Lenny Bruce, witness in the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial, and still active in his 80s, his gonzo Tale of Two Trials is gleaned from his original press coverage of the Patty Hearst trial for the Berkeley Barb. He analyzes how graffiti that read SLA LIVES was re-tagged as COLE SLAW LIVES, a “slogan that baffled tourists and convinced one visiting ex-Berkeleyite that a political activist named Cole Slaw was dead because there was graffiti saying he was alive.” In 60 pages, he blows holes in Toobin’s mainstream version, while saving the second half of his book to connect the denouement of the ’70s with the Jonestown Massacre and the trial of sugar-junkie Dan White, who murdered Harvey Milk and San Francisco Mayor George Moscone.

Krassner founded and edited The Realist magazine, a haven for “Free Thought, Criticism and Satire,” which features interviews with and contributions by famous novelists, comedians, and thinkers of the day. Imagine if John Oliver, The Intercept, and Eric Andre rolled themselves into one muckraking avenger: that’s Krassner. The entire February 1974 issue of The Realist is devoted to the SLA. He gave controversial conspiracy researcher Mae Brussell carte blanche to flex her theory that the SLA was a CIA plot. [1] This was published as the second installment of Brussel’s “Conspiracy Newsletter,” the first installment having been about the Watergate Scandal. To wholeheartedly believe all that Brussell cited (alas, she didn’t list her sources) is to be uncritical. But to be fair, many other newspaper articles and books, including Revolution’s End, corroborate the suspicious background of the SLA.

Toobin ignores this line of questioning entirely, and in doing so omits something indispensible to understanding the meaning of the SLA. Instead, he constructs a traditional-history filter for such information, especially blatant when he brushes against alternative press outlets such as the Berkeley Barb, and uses headlines like “Patty Freed!” to suggest that “hippies” were gung-ho for the SLA. The Barb printed various critical perspectives, among them the that “Cinque Called Police Patsy,” “Defreeze ‘Impostor’ Surfaces,” and a letter to the editor referring to Hearst’s state of jeopardy while in SLA captivity. The Barb was a contrarian voice that published contradictory “theories” about the SLA, covered the beat, printing satirical spin like Krassner’s illusory press conference, “The Crucifixion of Patty Hearst.” My point is that at a distance of 40 years, facts about the SLA can be and are still being cherry-picked.

Krassner values irreverence, based on his commitment to counter official lies that are routinely presented in the guise of truth. For instance, in 1975 when Krassner landed an “exclusive interview” with Patty Hearst for Crawdaddy, she was still on the run. Because of the raw nature of the “interview” — “And I became acquainted with my clitoris.” — the FBI paid Krassner a visit. The snag was, of course, Krassner had made it all up. Today, such subversive tactics have not only been copied by numerous comedians, but also compete in the realm of Fake News.

Krassner explains his method in Abakus: “While publishing The Realist, I never labeled anything satire or reality because I never wanted to deprive my readers the pleasure of discerning for themselves whether something was true or a satirical extension of the truth.”

Who do we trust? The question falls partially on an author’s approach. Toobin employs what he calls “narrative non-fiction,” with himself as the invisible narrator, focusing on egos of SLA members and the court trial. Brad Schreiber’s tack is not as pop as Toobin’s and discusses false-flag counterintelligence programs associated with LAPD Detective Ronald G. Farwell, director of the California Correction Department Raymond K. Procunier, and California Attorney General Evelle J. Younger. Schreiber’s evidence is in his bibliography, similar to Toobin’s “Notes” section and “Selected Bibliography.” Krassner samples other reference points with his own experience in a nonlinear comic analysis, pulling off deft lines, like “[t]he message of the trial was clear: Destroy the seeds of rebellion in your children or we shall have it done for you.”

A problem with all the SLA books is a lack of annotated citations, directing readers to the full sources (e.g., newspapers, magazines, reports, and communiqués), which this story desperately needs. Schreiber gets closest at this, but is stymied by redacted FBI records and the lack of even one definitive court case proving a “criminal conspiracy.”

Fox 2000 Pictures bought the rights to Toobin’s still untitled Patty Hearst project before he even wrote it. It has been reviewed warmly in The New York Times and Bookforum, while Revolution’s End has been panned by Publishers Weekly as “red meat” for the “conspiracy buffs.” By contrast, Krassner, a living legend, is forced to cannibalize his own writing at times because, currently, the commercial market places less value on his freewheeling style.

Interviewed on NPR and throughout his book tour, Toobin recounted how his publisher prodded him to pursue his subject. “I said to Bill [his editor] there must be a million books about Patty Hearst. So he said go check. And to my surprise and delight, I learned that nothing had been written about the Patty Hearst case in more than 30 years […] nothing new had been written.” When asked by the audience how the trial would be covered in the age of social media, Toobin deflects, “There would be more than one book, I wouldn’t have the field to myself.”

Of the three methods of reportage under review, Toobin’s method, although myopic, dominates general readership. A multidimensional perspective stretches the reader to understand a multidimensional event wherein actual people really got hurt, members of the SLA were deceived, and both the SLA’s fans and detractors were duped. Reality can be equal parts smoke and mirrors and human tragedy.

¤

Out in the Highland Park section of Los Angeles, the LAPD Museum houses dozens of old squad cars, an entertaining jailhouse installation, graphically pleasing posters, and three rooms devoted to the famous shootout with the SLA. Tie-dyed beaded curtains separate the displays and interactive videos glorify how the department handled the terrifying event. Children on a field trip to the museum are fed stereotypes about hippies and the “Latin-Style Terror” that the LAPD vanquished. After the SLA robbed the Hibernia Bank in San Francisco, the reductionist version fast-forwards to May 17, 1974, when six SLA members were immolated in a brutal shootout with the LAPD and the FBI. In a four-hour battle, the hideout house at 1466 E. 54th Street was pumped with thousands of rounds of ammunition, including grenades, and caught fire; it was allowed to burn to the ground. The entire event was broadcast live on national television, a technical feat in TV field recording, the first of its kind. It was a watershed media event that arguably accelerated the spread of SWAT teams, the War on Drugs, and the mass incarceration of people of color in the United States.

Patty Hearst, of course, was not in the blaze and remained on the lam for the next of 19 months, before she was apprehended on September 18, 1975. Then, her trial began.

Back in April 1974, before the death of the six SLA members, the editors at Rolling Stone ran a spread about the media manipulation of Patty Hearst, excerpting a letter from ex-members of the defunct Marxist-Leninist group, the Venceremos: “In effect, if not in intent, they [the SLA] are anti-working class, anti-revolutionary and anti-communist. If the SLA did not exist, the police would have to invent them.

Objectively, they are playing the role of provocateurs.”

Government infiltration from this period has been documented in several recent books, among them F.B. Eyes How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature (2015), Neither Peace nor Freedom: The Cultural Cold War in Latin America (2015), and Finks:

How the CIA Tricked the World’s Best Writers (2017). Infiltration of targeted college campuses in the 1970s, and of radical groups like the Black Panthers, has been documented. (The FBI considered the Panthers a “Black Nationalist Hate Group.”) The FBI’s killing of Chicago Black Panther Fred Hampton, laid out in Jeffrey Haas’s The Assassination of Fred Hampton (2009), underpins how commonplace infiltrating any group would have been in the 1973 political landscape. The Venceremos, Tribal Thumb, August Seventh Guerilla Movement (ASGM), United Slaves (US), United Prisoners Union — look up these Bay Area radical factions, some of which were heavily infiltrated, while others were straight-up front groups. What Schreiber and Krassner propose is that the SLA was a compromised radical group.

Toobin’s omission of this possibility is telling. His only nod to the concept of infiltration is when he describes Hearst’s jailhouse cooperation with the FBI, after her arrest, which made her in effect a “government informant.”

As Paul Krassner puts it, “If DeFreeze was a double agent, then the SLA was a Frankenstein monster, turning against its creator by becoming in reality what had been orchestrated only as a media image.” In a New York Times article published May 17, 1974 — the day of the fatal shootout — reporter John Kifner peeled back Donald DeFreeze’s origins as an agent provocateur. When Toobin brushes up against these implications, he covers himself with phrases such as “the most peculiar thing,” and in this seeming clueless statement:

“Remarkably, in light of this long series of crimes during the 1960s, Defreeze never received much more than probation.”

Schreiber goes deeper. He retells how DeFreeze became Cinque by fleshing out the role of Colston Westbrook, a behind-the-curtain operator whom Donald Defreeze accused in an SLA communiqué of being “a government agent” and put him on the “deathlist.” John Kifner’s article traced Westbrook’s activities to the Pacific Architects and Engineers, which he calls “a recruiting pool and cover by the C.I.A. for its Phoenix program, which included assassination teams, according to Bart Osborne of the Fifth Estate, a Washington‐based research group of former intelligence personnel who had turned against the Vietnam war.”

In The Life and Death of the SLA (1976), Les Payne (a Pulitzer Prize winner), Tim Findley, and Carolyn Craven also documented Westbrook’s association with Defreeze. Westbrook was hired to run the Black Cultural Association at the Vacaville State Prison Medical Facility, even as he was a communications instructor at UC Berkeley in the Black Studies department. There, in Krassner’s telling, “he became the control officer for DeFreeze, who had worked as a police informer from 1967 to 1969 for the Public Disorder Intelligence Unit of the Los Angeles Police Department.”

Toobin’s version never mentions Westbrook. He describes the Black Cultural Association as “a self-improvement club of sorts that offered classes on African American history and culture […] a fairly typical establishment response to the black power movement — an attempt by prison authorities to allow black inmates to express ethnic pride in a productive, nonthreatening manner.”

By contrast, in Schreiber’s description, “The BCA was ostensibly an education program designed to instill black pride in Vacaville inmates. In reality, it became a cover for an experimental project to explore the extent to which unstable or susceptible prisoners could be controlled for the purpose of infiltration of Bay Area radical groups.” Schreiber even dug up an open letter to the Barb where Westbrook cajoled DeFreeze and spun a theory that it was the white Maoists of the SLA that infiltrated the BCA.

¤

A classic example of a criminal conspiracy being transformed into a wide-ranging scandal is Watergate. French theorist Jean Baudrillard wrote about Watergate as a conceptual reversal in his famous Simulacra and Simulation (1981). “Watergate was thus nothing but a lure held out by the system to catch its adversaries — a simulation of scandal for regenerative ends.” Nixon is the subject of dozens of movies and plays; the United States feels retribution when they see Nixon fall, again and again. The idea of an event transformed into a regenerative simulation can be applied to the SLA.

William Safire, longtime New York Times columnist of “On Language,” tackled the phrase “Conspiracy Theory” in his November 5, 1995, column. In his quippy, kid-friendly style, Safire educates the reader: “According to the first Barnhart Dictionary Companion, published in 1982, conspiracy theory ‘has been widely used since 1973, perhaps sparked by the many theories about the worldwide energy crisis, which began that year.’” Of course, before Safire was the word guru, he was a conservative speechwriting guru for Nixon, prior to the dark days of Watergate. When a far-reaching scandal gets big enough, the suffix “–gate” is tacked on, a social ritual popularized by William Safire himself in the years following Nixon’s demise. Adding “–gate” to an event became a way to conflate serious corruption with tabloid sex scandals. In the public’s memory, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie’s Bridgegate competes with Janet Jackson’s Nipplegate.

But with the spectacle of Donald Trump, public opinion about “conspiracy” is undergoing a substantial metamorphosis. As John Oliver aptly noted on November 23, 2016, “Weird conspiracy bullshit has always been bubbling under the surface, but Trump was the first major candidate to harness and fully legitimize it.” When Trump tweets, “How low has President Obama gone to tapp [sic] my phones during the very sacred election process. This is Nixon/Watergate,” he martyrs himself as the victim, a tactic borrowed from Vladimir Putin to scramble any semblance of truth and dominate the news cycle. Ergo, Trump settles into his presidency as a neo-Nixon, even as he accuses his opponents of behaving like Tricky Dick.

What was once spoken about behind closed doors is now shared freely in the open air, with Trump associate Roger Stone saying, “Facts are in the eye of the beholder.”

This is how American Heiress sums up the last 40 years:

[T]he music stopped when the 1980s arrived. There was, essentially, no more counterculture; the term became obsolete. Radical outlaws like the members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, who even in their heyday were stragglers from the 1960s, virtually disappeared altogether. The FBI finally learned how to identify and prosecute politically engaged criminals, many of whom had turned to conventional crime, like drug dealing. Some were caught; others drifted away. In San Francisco, the AIDS plague arrived, decimating the gay community and sapping, for a time, the political energy of the city. The notion of revolution, which was never appealing to more than a handful of Americans, became absurd. Young people looked for inspiration not to the barrios of Uruguay but to the garages of Silicon Valley, across the bay from Berkeley.

This is a gross misrepresentation not because it’s racist or sexist, but because of its liberal and reasonable-sounding veneer. To unpack this paragraph would take too much space to engage in here. Suffice it to say that Hunter S. Thompson would not agree with Toobin. But others have told the story in more accurate ways, even if they have their own limitations.

The way the SLA has been portrayed illuminates the possibility of a dangerous future where historical incidents are repackaged, monetized, caricatured, and hung in a vacuum. The SLA and Patty Hearst continue to resonate in our collective mythology precisely because hidden within the smoke and mirrors is the very real urge to resist. It was always there. What is desperately needed is a mash-up of these three versions into one account, annotated for posterity’s sake, combining Toobin’s pop flare in the courtroom with Schreiber’s investigative chops unearthing intelligence overreach, and interlaced with Krassner’s perception and wit. Now that would be definitive.

M. W. Lipschutz is a writer, filmmaker, and visual artist who lives and works in Los Angeles.

[1] Brussell has recently been collected in The Essential Mae Brussell: Investigations of Fascism in America (2015, Feral house)