by Raymond Deane

Irish Left Review

March 10th, 2016

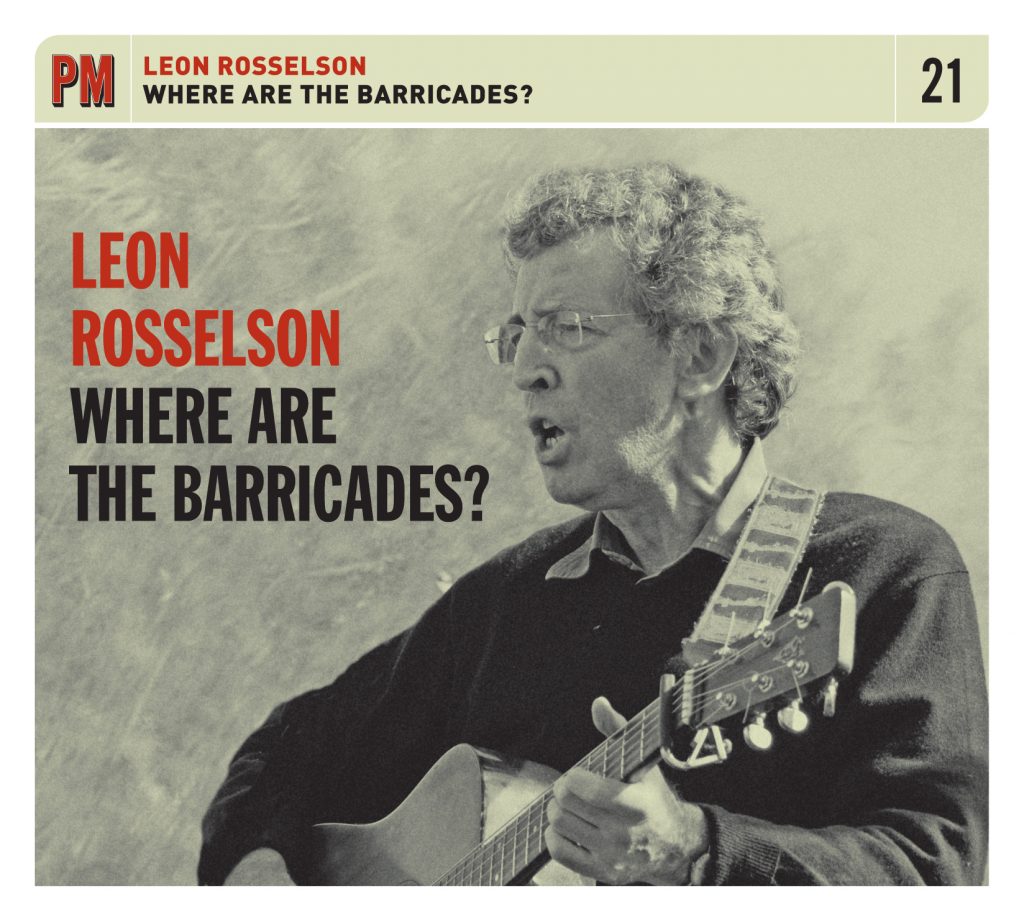

Five years after his 4-CD compendium The World Turned Upside Down – Rosselsongs 1960-2010 the radical English singer/songwriter Leon Rosselson has released a new album, Where are the Barricades? Rosselson turned 80 in 2014, so his announcement that “after some sixty years of songwriting… this is my final recording” is hardly shocking, but will nonetheless distress those for whom his consistent advocacy of social change and support for the underdog has long been an inspiration.

Rosselson, the son of communist Jewish immigrants to Britain, made his name contributing satirical songs to the classic 1960s BBC TV show That Was The Week That Was, and he has never abandoned a very English form of political satire. Indeed some more po-faced purists may well be aggrieved by the sheer frivolity of the first song on the album (the earliest version of which dates back to 1986):

Full Marks for Charlie.

He’s the bugbear of the bosses.

Workers of the world unite!

Charlie Marx is dynamite.

In fact the transmission of serious political comment through the medium of cheek, conveyed in a voice that in an earlier review I described as possessing a “vaguely Monty Pythonish quality (Eric Idle comes to mind!)”, is so characteristic of Rosselson that the listener’s response to his music may depend on her/his tolerance of the combination. To which I must add a further comment from that review: “When Rosselson sings, the vocal idiosyncrasies are inseparable from his intractable and endearing integrity.”

The satirical mode is conspicuous in Looters (“You smash up the shops and you get free stuff/ It’s all about the money nowadays…innit?”), Benefits (“Come all you skivers, welfare cheats...”), and the title song, Where are the Barricades? (here making its fourth recorded appearance) which effortlessly manages a direct quotation from the Communist Manifesto:

See how the bubbles are bursting

‘All that’s solid melts into air’

The stairs are beginning to rattle

And the rats are beginning to stare.

However, Rosselson’s range is wider than this. While he has admitted to avoiding love-songs (“love, a word that has rarely passed my songwriting pen”), he has instead composed what he calls “relationship songs” entailing “a sideways look at love, sex, marriage, relationships and angst…” Active Ageing is a comical example of this, while Marital Diaries are bitter-sweet slices of married life spoken by Rosselson and Liz (Elizabeth) Mansfield. To the latter (minus Rosselson) is assigned Paris in the Rain, an “attempt at an English French-style chanson”, beautifully accompanied on piano by Fiz Shapur. Fair’s Fair, originally recorded by Roy Bailey (who participates in a couple of songs on this album, but not this one) is a seemingly apolitical celebration of the fun of the fair, rollercoaster, dodgems and all. For Rosselson, it’s

“a song that suggested revisiting the past in order to recapture those more innocent, stress-free days, represented by a trip to the fairground where ‘smashing plates can be a lot of fun’ and ‘you’ll see it can be easy to pretend’ and we can ‘dream of sunny days that never end’. An exercise in nostalgia, in fact. (Private communication.)

Four Degrees Celsius, opening and closing with a line from the fourteenth-century poem Piers Plowman (‘On a summer season when soft was the sun’), is an enigmatic allegory that may or may not evoke ecological apocalypse.

I have previously described Rosselson’s anti-Zionist Song of the Olive Tree as “perhaps his most beautiful composition”, and perhaps the most powerful song on the new album is The Ballad of Rivka & Mohammed, the note on which in the CD booklet is almost an essay on Israel’s persecution of the people of Gaza.

In a sympathetic interview with Rosselson, which is much more than an interview, the English Jewish blogger Robert Cohen describes the song as follows:

A Nazi soldier smashes the head of Rivka, a seven year old girl wearing her new red dress in the Vilna ghetto in 1942. An Israeli soldier fires a shell onto a Gaza beach and kills Mohammed, an eleven year old boy playing football with his cousins in 2014. In the songwriter’s dream, Mohammed and Rivka take each other’s hand and “leave this world of war” – together. The Polish ghetto has been twinned with the Gaza Strip. Nazis are on a parallel with Israelis. And in life and in death, Rivka and Mohammed are together and equal.

Cohen asks: “Isn’t such a coupling of victims a dishonest slur against the state of Israel, a gross exaggeration, and an offence to the memory of the six million?” Rosselson replies:

The racism of the Nazis, dehumanising Jews (and so making them disposable), is matched by the racism of prominent Israelis and government spokesman dehumanising Palestinians, calling them ‘little snakes’, ‘two-legged beasts’, ‘drugged cockroaches’ and suggesting – as in an article in The Times of Israel – that there are times when genocide is permissible.

What is most remarkable about the song, apart from its courage, is its understated simplicity: the message is clear, and requires no rhetoric to hammer it home:

And I saw children still being slaughtered

The monster must have its fill

While the people with power turned a blind eye

And supplied the weapons that kill.

Rosselson’s decision to revisit the title song suggests that he sees few grounds for optimism in his country’s – or the world’s – recent history:

The plebs should be storming the ramparts

And whetting the guillotine’s blade

Singing capitalism’s in crisis

So where are the barricades?

However, the last song on the album, At Dawn (inspired by Yves Montand’s C’est à l’aube but replacing “its somewhat generalised imagery” with a “focus on the specific, the particular, the visual, which is what I always try to do”) rebuts any such fatalism. If this is truly Leon Rosselson’s farewell to the recording studio, then it is a stirring one indeed.

When the millions find their voices,

no more killing, no more war,

And the mighty will be humbled

at the dawning of the day

And their wealth and power will crumble

and be swept like dust away.

And it will be at dawn – at dawn.

****************************************************

Raymond Deane is a composer, author, and political activist. His memoir In my own Light was published in 2013 by Liffey Press.