By Mahir Ali

The Australian

February 6th, 2016

4 stars

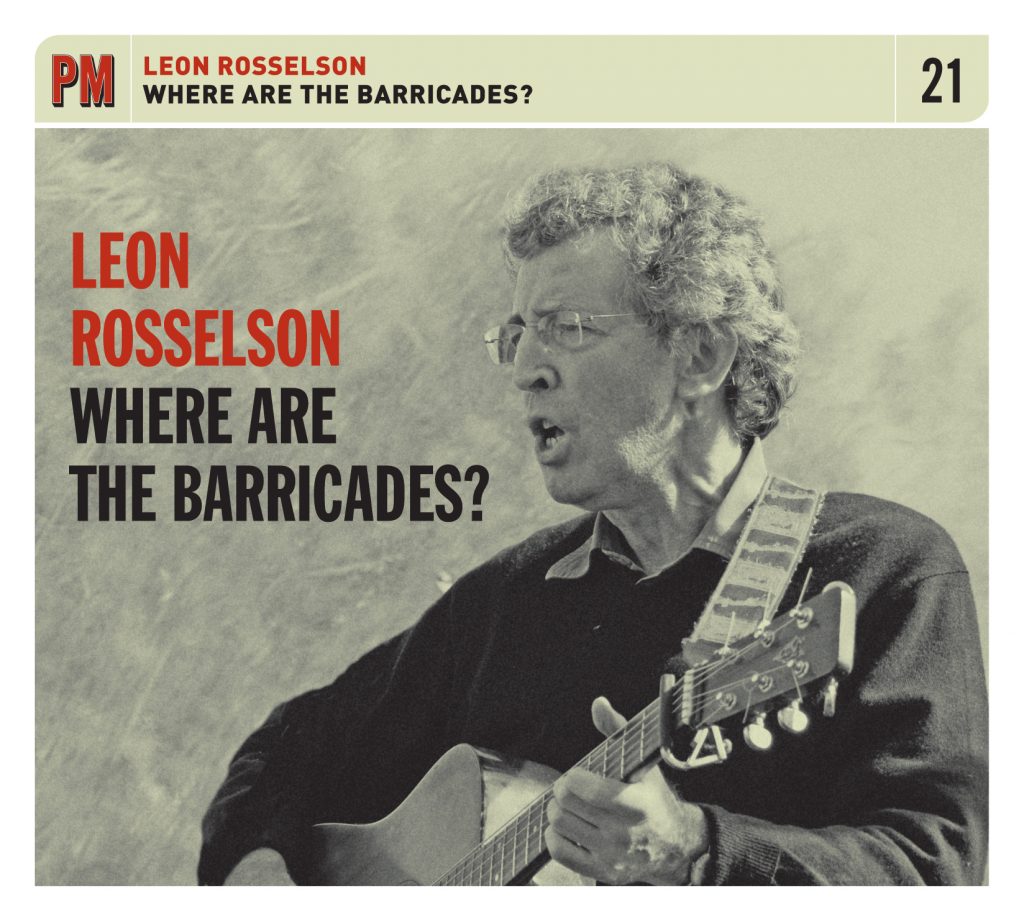

It

is entirely appropriate that Leon Rosselson’s final album should

include several examples of what he does best. The title song, aptly

prefaced with a blast from the past called Full Marks for Charlie (as in

Marx, rather than Chaplin), is a response to the global financial

crisis that was composed before the Occupy movement reared its head.

“Robespierre is wagging his finger,” it begins, “Karl Marx is scratching

his head / They ought to be shooting the bankers / But they’re giving

them money instead.” Looters, meanwhile, relates the London riots of

2011 to the dismal history of the British Empire, concluding: “Looting, a

great British pastime / The upper classes loot by stealth / Bankers,

tycoons, City gamblers / Siphon off the nation’s wealth / Centuries of

high-class looting / Payback time is overdue / Hyde Park, Kensington and

Knightsbridge / Watch out! Next time it could be you.”

In his more than 50 years as a singer-songwriter who has impressed critics more than the record-buying public, provocation has been Rosselson’s forte, albeit not exclusively in the sphere of politics. One of his greatest accomplishments lies in giving voice to the hopes and dreams of the voiceless, often eccentrics and outcasts who prosper or wither at a tangent from society.

The song Benefits portrays someone who “cheats” what’s left of the welfare state by using his vegetable patch to grow flowers instead. I’m Going Where the Suits Will Shine My Shoes, delivered in three different voices, with long-time collaborators Janet Russell and Roy Bailey pitching in, encapsulates the wishful thinking of the dispossessed. Dispossession also surfaces as a regular theme in Rosselson’s reflections on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As someone who once saw himself as a socialist Zionist but eventually found himself philosophically estranged from the Israeli state, he has frequently focused on parallels between the persecution of European Jews in the 1930s and that of the Palestinians since 1948, and The Ballad of Rivka and Mohammed poignantly pinpoints his concerns. Over the decades, Rosselson has regularly been referred to by critics as an outstanding songwriter, and he has long been esteemed within the folk fraternity, with the likes of Martin Carthy and Frankie Armstrong serving as regular collaborators. The fact that fame and fortune have passed him by arguably testifies to his authenticity as an artist who took his cues from Georges Brassens and Jacques Brel rather than Ewan MacColl. It is not particularly surprising that someone with Rosselson’s wit, erudition and sense of history has troubled the charts only once, with Ballad of a Spycatcher, recorded with Billy Bragg and the Oyster Band, back in 1987, or that his The World Turned Upside Down is often misconstrued as a 17th-century folk song. At 81, Rosselson has every right to call it a day. But his singing and songwriting has always been a calling rather than a career, which would suggest this album may not be quite the end of the story.