By Charlotte Stretch

3:AM Magazine

There’s something not quite right about John King’s latest book, Skinheads. Settling down to read about this unique and well-documented subculture, I find very little to tally with my own view of skinheads; they aren’t neo-Nazis, they aren’t hell-bent on securing “rights for whites” – they’re not even, in truth, particularly violent.

It is a remarkable feat of King’s writing that he manages to present an utterly fresh yet honest portrait of this group. “I wanted to write about skinheads just because [there are] a lot of the things said about them which I don’t think are true,” he says. “I just wanted to show them as normal people, really.”

King’s book is a neat confrontation of the middle-class fear that the values and beliefs of skinheads are, ultimately, not as extreme or unfamiliar as we may care to admit. “My idea was to be able to show that it [racism] happens each way, and there’s a unity between people,” he explains. “The whole interesting thing about skinheads is, they listened to black music in the sixties. It does connect up with the upper class view of those people not having a history or a story or anything worthwhile. It’s quite interesting in the way that skinheads are considered right-wing Nazis, whereas, say, the Teddy boys aren’t remembered like that, or spivs, or any other gangs. You know, why is it just that? And a lot of it is to do with the look, I think. I mean, there is truth in that, but obviously, the majority are into music, they’re into football, they’re not particularly political. So instead of focusing on that, I just decided to focus on ordinary people who happen to be skinheads.”

Despite King’s determination to capture skinhead culture accurately, the fact is that this is not really what lies at the novel’s core. Skinheads is a tale of family, of growing up and of being an adult. Central to the action is Terry English, the widowed boss of a minicab firm about to hit his fiftieth. When he discovers the Union Jack club, once a thriving magnet for the community but now empty and defunct, he decides to bring the club back to its former glory.

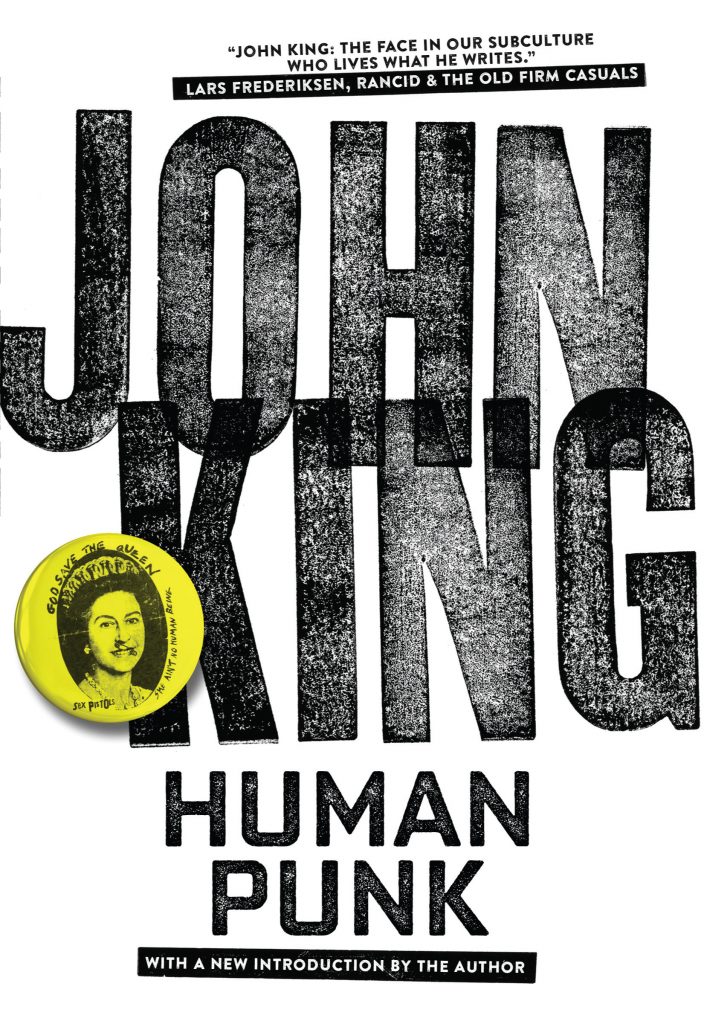

“It’s part of a loose trilogy, [with] Human Punk and White Trash,” King explains. “ I suppose one of the ideas was to write about a family, basically, and different generations.” Adding to this is a set of inventive structural techniques which lend the book a sophisticated, edgy energy. “I decided to write the past sections in the present tense, and the present bits, the more modern and up to date bits, in the past tense. [It’s] the idea of time, in a circle, also the repetition of culture: how family see each other, how things are passed down through families. There’s always this idea of youth as something separate, which I don’t really believe, because I think a lot of influence does come from families. I mean kids now, you know, they could have been kids in my day, you know they’ve got very similar fashions, very similar interests.” Once again, it seems, King is keen to explode the myths perpetrated through the media: anyone reading the papers would be inclined to disbelieve that today’s happy-slapping, gun-wielding generation could have anything in common with their parents’ generation. But, as King argues, this is simply untrue. “Kids I know, they’re great,” he insists. “They’re of no real difference to us. I think it’s much more peaceful today, I really do. I know there’s drug-related gang crime where you have stabbings and stuff, but generally I think kids are pretty chilled out. If you went back and you lived in the seventies, people walking around with offensive weapons: it was a much much rougher time. Much rougher.” Much of this misconception, King believes, stems from the media, and in particular a wildly disproportionate focus on youth crime. “I think the media is bigger than ever; it’s not really about news any more, it’s about a weird sort of entertainment,” he says. “There was violence and trouble in the old days, and there were youth panics about that – like with football hooliganism, which did occur; of course it did. But if you go back to the sixties, you think every Saturday you had fifty, sixty, seventy thousand young men crossing the country smashing up high streets, it’s a lot different. It’s a good generation now.”

Football hooliganism is, of course, exactly where King was given his big break: his first novel, Football Factory, dealt with issues of violence among fans and, on a greater scale, introduced the enduring theme of much-scrutinised male subcultures. “With the football thing, I did tie that into the generations that grew up with the war,” he says. “War as an ideal of, you know, “this is what England did”. And so football became a focal point for a lot of areas that were cleared out; it became a focal point for the communities.”

For King, the post-war era has yielded an overwhelming degree of change within British society. One senses, even before he begins discussing this fully, that these changes aren’t necessarily welcomed by him; he speaks nostalgically about pre-war writers in Britain – the kind of writers now published by his own publishing imprint, London Books. “I just started getting interested in those books because, having read them, I found them very modern, actually; very imaginative, very political. Very honest books; more modern, in a lot of ways, than a lot of stuff that’s published today.” He enthusiastically discusses his favourites among these books, although admits that, “I wasn’t a big reader as a kid. It was only really in my late teens, early twenties, that I started reading.”

One of the most powerful moments in Skinheads occurs when Ray, a street-punk whose violent episodes create his own downfall, discovers the works of George Orwell – a writer who unlocks a new world for Ray. Violent tendencies aside, this is a direct transposition of King’s own views, as he enthusiastically cites Orwell as his biggest influence. “He’s my favourite writer,” King beams happily. “I think Orwell was actually quite a big influence on a lot of the punk bands. Before 1984, the term “Nineteen-Eighty-Four” was a term for a brave new world; it was dictatorship, totalitarianism. He’s a big motivation in terms of his ideas and his honesty.” Were it published today, I ask King, would Nineteen-Eighty-Four have the same impact? “Probably not,” he says, “because it’s of the time. Those things are here. Brave New World is here. Maybe in the seventies or even eighties you could understand that [Nineteen-Eighty-Four] more; it’s almost like now it’s gone beyond that. And It’s speeding up. You can see it in public spaces like pubs, churches, schools; they’re getting closed down. A focal point stripped bare and turned into a yuppie flat, or a hi-tech pizza place with a wood burner, and then six months later it’s empty. Those focal points are gone, and those public spaces are gone. That’s why I wrote about the Union Jack club; something that was taken out of the equation by Thatcherism.”

As the interview draws to a close, we return to the subject of London Books, and he offers to send me a list of his own recommendations. I’m interested in reading them, not least because, over the course of our conversation, I’ve found myself agreeing with King’s vision of an England gone astray. He’s quick to point out, though, that for the most part he’s happy with the way things are. “It’s not supposed to be a stuck in the mud idea,” he says. “Of course things should change — there are a lot of things that are better now. Life’s a lot easier.”

“Those books are like almost little documentaries,” he goes on. “You just get glimpses of what was going on; what the place was like. I like the West End, because there’s loads of pubs up there that haven’t changed. Pubs I’ve been going in for thirty years, they haven’t changed at all. Soho was that sort of focal point in the old days, for more cosmopolitan places. When spaghetti was exotic. To get a bowl of spaghetti, you know, was exotic.” He smiles at the thought. “That’s before my time, obviously; I’m not that old.” Perhaps not – but part of me can’t help but feel that he really ought to be. His understanding of the past and how it has shaped us lends a remarkable credibility to his accounts of pre-war Britain, as well as informing a brilliant portrait of contemporary Britain. A bowl of spaghetti might not create much excitement anymore, but writers like King certainly do.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Charlotte Stretch lives in Brixton where she is a freelance writer and an editor of 3:AM. She is currently working on her first novel.