By Gary Roth

Interface

Volume 6 issue 2

December 7th, 2014

Francis Dupuis-Déri’s defense of the Black Bloc is disarming in its subtlety. “The Black Bloc,” he tells us, “is not a treatise in political philosophy, let alone a strategy.” For Dupuis-Déri, it is simply “a tactic” (p. 3). But tactics too, as John Berger once pointed out, are often wedded to implied philosophies and unarticulated strategies.

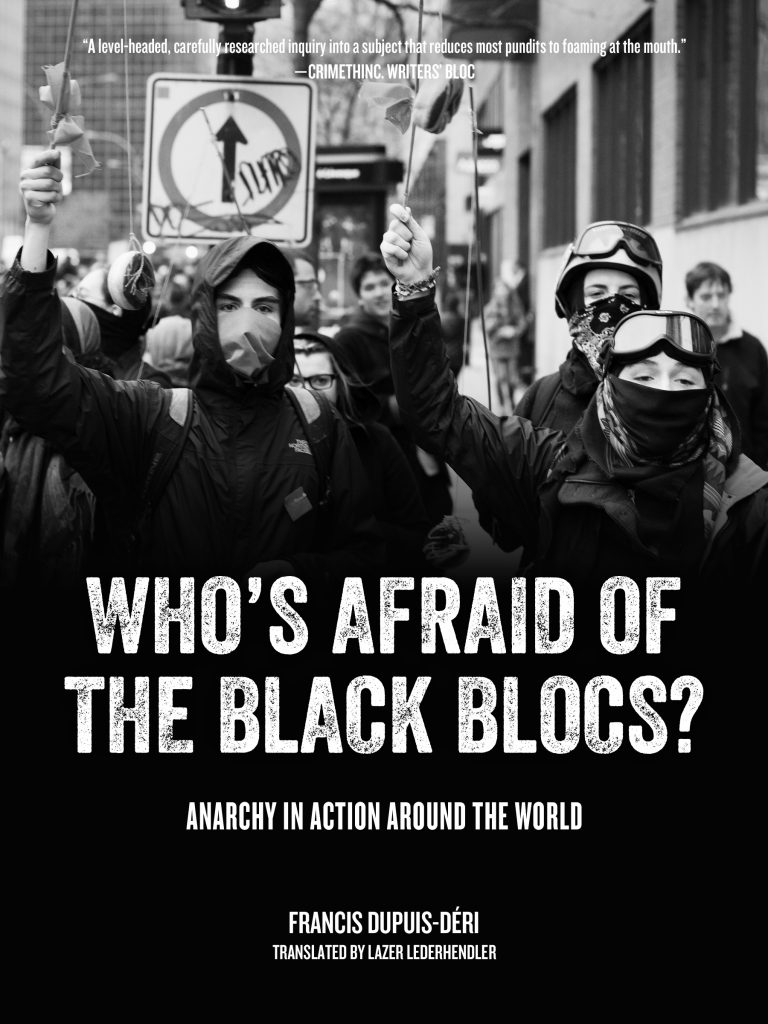

Besides, the very purpose of Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs? is to give voice to Black Bloc participants. They explain in their own terms why these “ad hoc assemblages of individuals or affinity groups that lastfor the duration of a march or rally” have been ever-present during the last few decades (p. 2). They have emerged as something of a cultural icon. Known for their characteristic use of black clothing and face masks, Black Bloc participants tend to be deeply ethical and deliberate in their decision-making, although not usually in ways appreciated by their many critics and opponents. This speaks to the huge gap that exists between the portrayal of the Black Blocs in the media and the self-consciousness of those who take part in them.

Black Blocs have influenced public discourse out of proportion to their actual size, which has ranged anywhere from a few odd individuals to several thousand people who coalesce at demonstrations seemingly from nowhere and then disappear just as anonymously. Dupuis-Déri traces their roots to West Berlin’s squatter movement of the early-and mid-1980s. He acknowledges too that they are more properly considered a form of struggle specific to this new century.

They are part of the same general trend as the “occupation of squares” that stretches from the Arab Spring to Spain’s Indignados to Zuccotti Park, the Maidan in the Ukraine, and more (Endnotes Collective 2014). Black Blocs have been a feature of the alter-(anti-)globalization protests of the last decade and a half and have now evolved into a regular component of virtually every popular movement in recent years.

The notoriety that accompanies the Black Blocs derives from their deliberate pursuit of “symbolic economic and political targets” (p. 33). Large corporate entities and government buildings are sought out almost exclusively. In the urban areas where the Black Blocs have been active, this means the chain stores, with bank facades and the window fronts of well-known retail outlets such as Starbucks and Gap receiving special attention. In some places, public buildings in central city locations have been preferred instead. In either case, the Black Blocs direct their violence towards inanimate objects, overpriced articles of consumption, and ineffective and corrupt ruling strata, where “the target is the message” (p. 43). As Dupuis-Déri explains, the Black Blocs have modernized and also revitalized the anarchist doctrine of “propaganda of the deed.” The Blocs have been rather scrupulous to avoid small businesses, community centers, homes, and libraries, a pattern that itself gives a clue as to the worldviews that form their political sensibilities. Violence against people is taboo (except when responding to police violence), whereas their critics, as Dupuis-Déri points out with numerous quotes, tend to defend people and things as if these were equivalent categories.

If property damage defines the Black Blocs in the public’s eyes, the Blocs regularly assume other functions at demonstrations. This has included the hauling of food and water to the protest sites, arranging transportation and lodging for out-of-town demonstrators, providing medical support, and serving as a protective barrier that shields non-violent protestors from the police and security forces. On some occasions, they have helped divert official attention from protest sites by creating a ruckus in another area. Because the Blocs function as affinity groups, on-the-spot coordination comes easily. The groups are anti-hierarchical, with decisions reached through consensus. They are capable of making tactical choices in conjunction with other groups, even though their ad hoc formations tend to preclude negotiations that get overly complicated.

One doesn’t wander into a Black Bloc accidently. Participants are typically veterans of previous protests and have received training in direct action tactics and ethics, legal issues, and safety measures. Many of them object to individuals (“activism tourists”) not already a member of an affinity group, since their exclusion cuts down on provocateurs and other violence-prone individuals (p.102). Black Bloc participants often come equipped with shields, helmets, gas masks, and anti-tear gas cream in order to protect themselves from police attacks, and with chains, locks, rocks, clubs, slingshots, and Molotov cocktails to counteract police aggression.

The Blocs now come in multiple colors. Besides the Black Blocs who are known primarily for their trashing of downtown areas, Red Blocs are clusters of leftists still supportive of hierarchical organizations and state-dominated social systems. White Blocs refer to the exclusive use of non-violent tactics. Pink Blocs are generally the most colorful, since they combine antics, art, and satire. A “Billionaires for Bush and Gore” contingent protested the 2004 Presidential election campaign in the United States with formal attire and fake banknotes distributed to police officers in thanks for their role in suppressing dissent. At another demonstration, protestors carried fishing poles with donuts as bait in an attempt to lure the police to them. Examples like these offer Dupuis-Déri ample opportunities to discuss the nuances of Black Bloc beliefs and practices.

Symbolism aside, the Black Blocs are demonized by police, political officials,scholars, journalists, and also other leftists, which Dupuis-Déri documents extensively despite the overall brevity of his book. The mis-characterizations projected towards the Black blocs are both crude and predictable, as: thugs, vandals, anarchists, trouble-makers, prone to violence, a mindless minority, soccer rowdies, proto-fascist paramilitaries, and more. The critics from the left are the most difficult to fathom. The Black Blocs tend towards a mixture of “Marxism, radical feminism, environmentalism, anarchism” (p. 24). Despite this, two issues come to the fore repeatedly—violence, whether directed against property or the police, and the refusal to follow the dictates that government officials and the security forces set down for protestors.

For the Black Blocs, “peaceful methods are too limited and play into the hands of the powers that be” (p.38). They are anti-establishment and reject a notion of representation which presupposes homogeneous communities. This undercuts other groups by limiting their ability to step forward as “people’s representatives” and thereby influence public policy. The Blocs, on their part, have been accused of hiding amidst non-violent demonstrators, a criticism that hit home. In recent protests, they have been overly conscientious about not letting this occur.

Opponents also accuse them of antagonizing the public, even if just the opposite seems to be true. Black Bloc activity tends to boost interest in anarchist ideas and activities. Some Black Blocs have called for a “diversity of tactics,” a matter not well received by these other groups, despite the divide between spokespeople who denounce the Blocs and everyday protestors who want something more than just a peaceful, respectful protest that is easy to ignore.

Dupuis-Déri picks apart just about every negative characterization hurled at the Black Blocs, one of the several strengths of his book. The “propagandhi” of non-violent activists is his special focus. Sometimes, though, he gets lost in arguments not quite germane to contemporary reality. He reaches back to the 1500s, for instance, to show that not just anarchists but also dissenting Christians targeted the royalty for assassinations. Since assassinations haven’t been part of the anarchist tradition for nearly a century already (despite the mythology), the entire discussion becomes a bit unreal. He also relativizes anarchist violence by pointing to the troubled and often bloodied track record of liberalism. His overly brief discussion of the two traditions glosses over significant differences in which the latter’s violence is a product of its use of the state as a means to consolidate and defend its rule, whereas anarchism has rarely ever been tested on that score.

Perhaps most disturbing is Dupuis-Déri’s discussion of the cathartic effects of violence, its psychological benefits. Reminiscent of the pseudo-scientific justifications used by fascists and devotees of brutal sports, violence becomes a form of creative expression. Dupuis-Déri speaks in terms of “restorative violence” (p. 85). These are dangerous ideas, and to say that “emotions are rooted in a social context and a political experience” is only to say the obvious(p. 90). Even overlooking the fact that emotions are also innate, what else could they be except socially-generated and constructed?

What can be said, and which Dupuis-Déri emphasizes with great effect, is that Black Bloc anarchists are much more conscientious about the use of violence than are the many and various security agencies arrayed against them. Police violence is mostly random and unprovoked, directed not only at the Black Blocs but at non-violent demonstrators and bystanders alike. Anarchists are categorized as “pre-terrorists,” subject to intense surveillance, and heavily infiltrated (p. 150). Masking both hides Black Bloc participants and also makes infiltration easy. But also, because they fight back, the police are more hesitant to abuse and brutalize protestors. The Black Blocs both draw and repel repression.

If Dupuis-Déri pushes his discussion further than necessary, it’s because he wants to dissect every possible criticism made of the Black Blocs. Some discussions might have been carried further. Gender dynamics is one such area.

Dupuis-Déri is quite conscientious in describing women’s roles within the Black Blocs. All the same, the Blocs remain overwhelmingly young and male, precisely the demographic that defines violence in society at large. He mentions that anti-fascist blocs tend to be predominately male, while anti-racist blocs attract a preponderance of females. These are the sorts of differences that he might have pursued in much greater depth.

Dupuis-Déri considers the Black Blocs to be “an image of the future” (160). It’s an image, however, that is clad in black and masked. It is an appropriate metaphor as well for Dupuis-Déri’s Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs? Anarchy in Action Around the World–a view of things to come that one can’t quite discern clearly but only watch in action. Uneven in parts, it is nonetheless highly informative and provocative throughout.

References

Berger, John. (1974). The Look of Things: Essays. New York: Viking Press.

Available:

http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/isj/1968/no034/berger.htm).

Endnotes Collective.(2014).“The Holding Pattern.”

Endnotes 3. Available: http://endnotes.org.uk/articles/18).

About the reviewer

Gary Roth is the author of Marxism in a Lost Century: A Biography of Paul Mattick (Brill/Haymarket: 2014/2015) and co-author with Anne Lopes of Men’s Feminism: August Bebel and the German Socialist Movement (Humanity Books:2000).

garyrothATandromeda.rutgers.edu