Sprout Distro

December 3rd, 2014

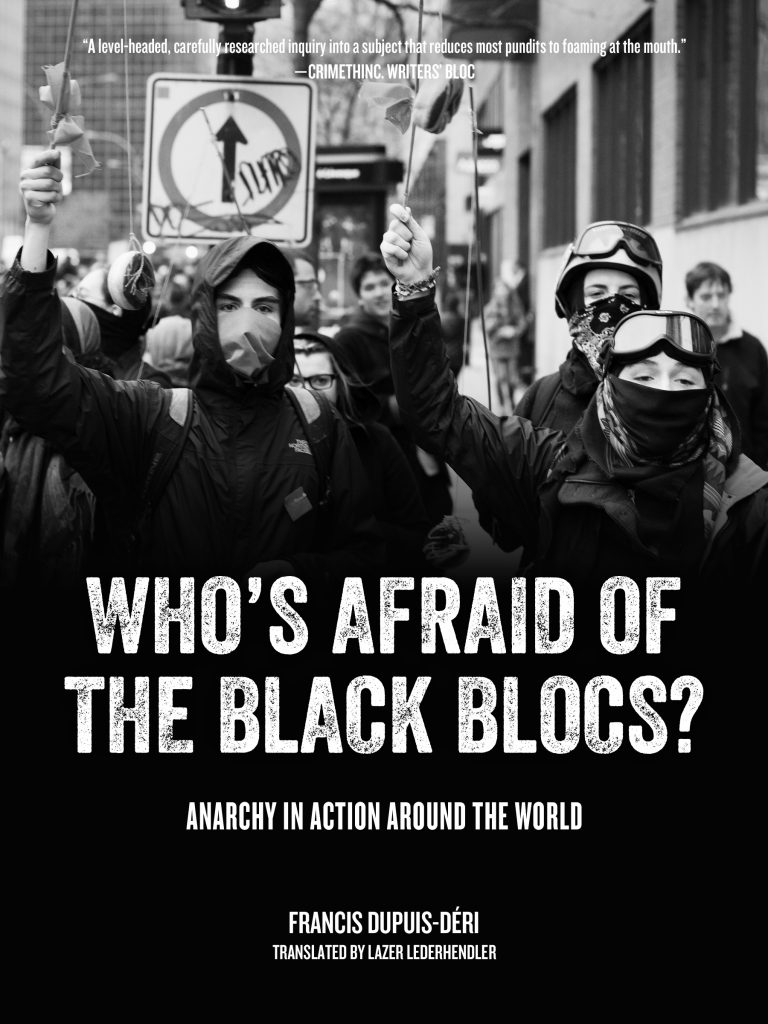

Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs? Anarchy in Action Around the World by Francis Dupuis-Déri is an attempt to objectively explore and examine the black bloc tactic by casting aside the stereotypes and political dismissals common both in the mainstream media and amongst various radical groups. The book draws on extensive research including interviews with black bloc participants in various actions over the past 15 years (the Quebec student strike in 2012, the Toronto G20 Summit in 2010, the Évian G8 Meeting in 2003, and the Quebec City Summit of the Americas in 2001), research into publications (communiqués, zines, etc) by black bloc participants, and observations garnered from the street.

The author—Francis Dupuis-Déri—has been a close observer of black blocs and a participant in anti-capitalist politics, having been a member of the Convergence des luttes anticapitalistes (CLAC) in Montreal. The 2013 edition of this book is a completely revised English version of a book that was originally published in French in 2003. The English edition offers entirely new perspectives, taking into account recent mass protests and new uses of the black bloc—effectively showing that the tactic, while always evolving, has remained a constant feature of anarchist street protests across the world for nearly 15 years. In the end, Dupuis-Déri shows that the black bloc is a serious manifestation of anarchist beliefs and that as one of the more visible manifestation of anarchist politics, it is worthy of a nuanced exploration that moves beyond shallow analysis.

An Introduction for the Uninitiated

At its core, Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs? provides an introduction to the black bloc tactic and the anarchist ideas that generally accompany it. The author gets the basics right, accurately describing the tactic, explaining its use, and making tentative statements about the politics of the black bloc. Whereas countless others over the years—from critics on the left to government agencies—have sought to portray the black bloc as a formal group, Dupuis-Déri avoids making that mistake. Instead, the author explains that black blocs differ dramatically from bloc to bloc and that they tend to be an assemblage of affinity groups or individuals, depending on the level of organizing that has been done in advance. They can range from a dozen people to hundreds, with purposes that range from defense of demonstrations to aggressive attacks against property and police.

The author traces the history of the black bloc tactic to the autonomous movement that emerged in Germany in the early 1980s (24). The autonomous movement was an anti-authoritarian movement that blended a variety of ideological influences—Marxism, radical feminism, anarchism, and environmentalism—while advocating for a politics based on individual and collective autonomy in the “here and now” (24-25). In practice, this meant rent strikes and squatting buildings which the movement used to develop a number of different hubs of activity from cafes and meeting spaces to infoshops (25). Black blocs originally grew out of street confrontations aimed at defending squats and attacking fascists, with the term being used to describe the autonomen would show up with a variety of helmets, shields, clubs, and projectiles and combat the police (25). According to Dupuis-Déri, the tactic spread to North America through “the punk and far left or ultra-left counterculture via fanzines, touring punk music groups, and personal contacts of traveling activists” (30). Early uses of the tactic took place at a protest in Washington DC in January 1991 against the Gulf War (30) and it was adopted by the militant anti-racist movement throughout the 1990s (31). Following the targeted property destruction undertaken by a black bloc at the Seattle World Trade Organization (WTO) protests in 1999, the black bloc got considerable media coverage, both in the mainstream and leftist press (33). This led to the spread of the tactic throughout the broad alter-globalization movement.

Dupuis-Déri argues that the black bloc is a manifestation of anarchist ideas, a specific and direct response to capitalism and the state. Rather than being so-called “irrational” acts of destruction, the confrontations and destruction undertaken by the black bloc are choices based on a specific worldview. Everything, from the way black blocs are organized to the choice of targets follows anarchist principles (42). Aside from demonstrating a political critique of the existing order, black blocs also are informed by emotion, with Dupuis-Déri arguing that it is joy and rage that motivate many participants (83-85). The author asserts that these “…emotions are rooted in a social context and a political experience. Direct action is a reaction to feelings of injustice and to situations of domination, inequality, and systemic violence” (90). Through black bloc actions, anarchists are able to temporarily liberate space and create experiences outside the norms set by the state and representative political organizations (99). Similarly, while black blocs are often criticized as being divisive and destructive to various “movements,” Dupuis-Déri argues that black blocs embody a critique of representation, both of the state and various “progressive” groups that routinely denounce black bloc tactics (127). The author rightfully points out that anarchists reject the politics of representation, arguing that efforts to “represent” the interests of the multitude result in oversimplification (126). Therefore, the direct action that a black bloc engages in provides both a new direction and a critique of representation.

Re-Examining Old Controversies

Seemingly no discussion of the black bloc would be complete without examining the various “controversies” that have surrounded the black bloc tactic as it has spread across the globe. Many of the common debates are taken up, including the discussion of violence in social movements, that it invites repression, whether or not the participants are just apolitical, charges of sexism, charges that black blocs alienate the working-class, and more.

For those familiar recent anarchist history, most of these conversations have been had at length, even though clear conclusions may not not have been found. As would be expected from an author sympathetic to the black bloc, Dupuis-Déri argues that the violence engaged in by the black bloc is insignificant when compared with the structural violence of the capitalism on a daily basis. It’s a relatively standard dismissal that many anarchists have already adopted, but is probably always worth pointing out. Dupuis-Déri further argues that black blocs also do not engage in violence against people, with the exception being armored police who are prepared to do great harm to demonstrators. Similarly, charges that the black bloc invites repression are easily debunked, with Dupuis-Déri providing numerous examples of authorities’ intent to repress protests regardless of their militancy. While militant threats may be used to provide an immediate pretext for repression, it is often just a way to justify police tactics that were planned well in advance. Another common charge, that black bloc participants are just mindless hooligans or young thugs, is dealt with by way of the author pointing out that most of the black bloc participants he interviewed were experienced activists or were involved in various community and political organizations (37).

In discussing the question whether or not the black bloc is alienating to the “working class” or the mainstream, Dupuis-Déri offers some interesting insights. He provides numerous examples of experiences on the streets where diverse groups of people of different backgrounds have supported black bloc tactics both in the moment (even in some cases by joining in) and afterward in expressing support (sometimes formal as was the case with Brazil’s State Union of Education Professionals [SEPE]) (124). Furthermore, there is a good discussion of the idea of “civil societies” and “public opinions” (118). Dupuis-Déri points out that rather than there being one monolithic “public” or “society” that can be alienated by black blocs, there are different segments of the population that respond differently based on their own individual feelings. As a black bloc participant points out, the assumption about a monolithic audience is usually that it is “white and middle class” (118). The author acknowledges that while violence does attract and dominate media attention, it may have a more positive effect that what is often assumed (117). Citing a study of media coverage following the Seattle World Trade Organization (WTO) protests in 1999, Dupuis-Déri explaining that it “boosted public interest in anarchism” (118) by resulting in more visits to anarchist websites and more stories about aspects of anarchism beyond black blocs including “anarchist soccer leagues, book fairs, and so on” (119). He concludes the discussion “there is no truth to claims that the operations of the Black Blocs necessarily widen the gap between anarchism and ‘ordinary’ working-class citizens” (124).

As with the discussion of whether or not the black bloc is alienating, the charge of sexism often leveled at the black bloc goes in some interesting directions in Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs. While highlighting various accounts and experiences of women and queer folks who have participated in black blocs, Dupuis-Déri acknowledges that men have often retained aspects of their male privilege, including within black blocs (107). Based on firsthand interviews, there are stories of women making banners while men practiced their slingshot skills (107), women shopping for supplies (107), women doing more preparatory work in terms of reconnaissance while men took glamorous roles in the streets (107-108), and observations of men who often function as “lone wolves” in “individualistic ways (110-111). By discussing concrete examples rather than reducing the discussion to the all-too-common and ridiculous charges that violence is masculine, Dupuis-Déri manages to give the discussion new relevancy.

While referencing more recent debates and controversies about the black bloc such as Chris Hedges “cancer of Occupy,” Dupuis-Déri doesn’t really delve into other shifts in anarchist thinking over the past ten or so years. For example, there is relatively little discussion of the role of insurrectionary anarchism, which has in some ways challenged the traditional idea of utilizing black blocs in the context of a mass street confrontation (60-61). At times, other criticisms are referenced, such as the “After We Burnt Everything…” discussion about the Strasbourg NATO Summit and discussions happening in Greece about the use of black blocs (59). A 2002 piece “Has The Black Bloc Tactic Reached The End Of Its Usefulness?” is referenced as well, but that question seems to be answered both in the book and in the streets as numerous black blocs have had varying degrees of “success” over the past decade.

In Conclusion

Ultimately for anarchists and others already familiar with the black bloc tactic and its history, Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs? doesn’t cover much new ground. Aside from relaying some recent history of black bloc actions in the Montreal student strike of 2012 and providing a relatively international perspective on the tactic, there isn’t a lot of new information here. The historical background isn’t substantially different from what one could find in shorter zines such as Can’t Stop Kaos: A Brief History of the Black Bloc, nor does it provide a practical and tactical introduction to using the black bloc tactic (for that, see zines such as Blocs, Black and Otherwise and How It Is To Be Fun). At the same time, the book doesn’t really have the level of passion that would draw in people new to anarchism. It gives a fine introduction and a detailed analysis, but it lacks the punch that would make readers want to set down the book and bloc up.