In the Context of Judith Clark’s Renunciation

by JMP

M-L-M Mayhem!

January 13, 2012

According to a recent New York Times

article by Tom Robbins, Judith Clark, former Weather Underground member

who was arrested in 1981 for the attempted robbery of a Brinks truck,

has renounced her radicalism and is now politically “rehabilitated.”

Robbins describes pre-rehabilitated Clark as if she was a member of a

religious cult: she was a “militant zealot,” a member of “a wild tribe

of radicals,” a “dogmatist”—in essence, the victim of leftist

brainwashing. For Robbins and his ilk, the actions of Clark and other

1960s-1970s U.S. militants were an insane response to a sane society

that just needed the help of a few enlightened liberals rather than a

sane response to the insane reality of capitalism. Now Clark has

recovered her sanity, now she has healed from the madness of

revolutionary ideology, and so now, Robbins argues, she should be let

out of prison and allowed to become part of productive liberal

society—after all, seventy-five years of incarceration for simply

driving a getaway car is only permissible if she still believed that

robbing an armoured truck to fund a revolution was morally okay. Before

now, before her “rehabilitation,” she was simply a brainwashed stooge.

But

as the friend and comrade who introduced me to this article [thanks

Jude W!] pointed out, the fact that Clark’s radical politics are treated

as an instance of cult-like brainwashing is extremely ironic in the

context of state brainwashing described unintentionally by Robbins.

Clark’s “rehabilitation” comes after two years in solitary confinement

where a sociologist makes her feel guilt about the child she was forced

to leave behind when she was imprisoned. Anyone who knows anything about

the treatment of revolutionaries in the prison-industrial complex, and

the mechanisms that are levelled upon people who resist status quo

ideology (for more repressive, by all accounts, than what is suffered by

the general prison population), also knows that solitary confinement

and the interrogations connected to solitary confinement are designed to

politically condition and “rehabilitate” prisoners. That is, Clark’s

reconversion to liberal ideology is not some honest recovery of “sanity”

but an instance of ideological control and psychological torture—an

instance of brain-washing.

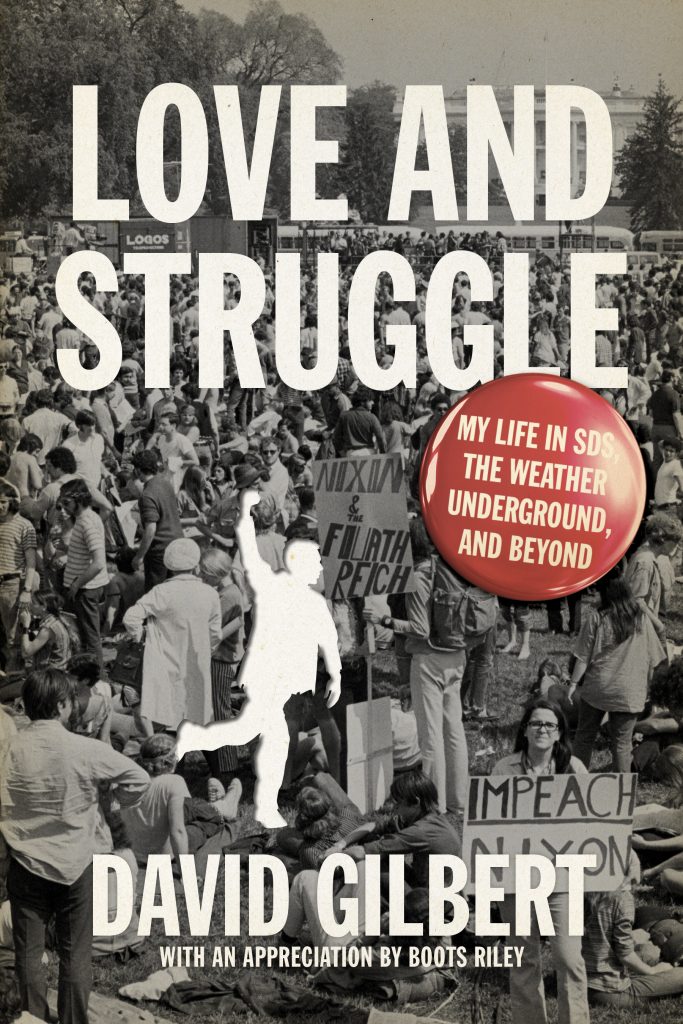

What is interesting about this recent

news of Judith Clark’s “rehabilitation,” though, is that it has happened

around the same time that one of her former imprisoned comrades, David

Gilbert, had finally written and published his memoir, Love & Struggle: my life in SDS, the Weather Underground, and Beyond.

Unlike Clark, however, Gilbert refuses to be politically rehabilitated,

has resisted decades of attempted brainwashing and psychological

torture in concentration camps of the American prison system, and is

generally known as one of the “poster-boys” of U.S. political prisoners.

Although Gilbert has written other books, Love & Struggle is

his first attempt at a thorough and systematic autobiography. Indeed,

Gilbert claims in the introduction that he has long resisted writing an

autobiography because the idea “always felt too self-involved.”

Thankfully, for those of us who have wanted to read these memoirs, the

son Gilbert has only known through conjugal visits convinced him

otherwise.

Except Love & Struggle is not simply

another collection of remembered politics on the part of a revolutionary

who is still a committed revolutionary communist, nor is it just a

who’s-who inventory of the radical 1960s and 1970s—though it is, in some

ways, both of these things. But Love & Struggle is truly

worth reading for the following reasons: a) it is a book written by an

imprisoned revolution who (unlike his former comrade Judith Clark)

continues to resist political rehabilitation; b) parts of it are grouped

around revolutionary concepts, leftist in-jargon that is usually

obscure to a new radical, that are demystified through Gilbert’s

autobiography; c) it is an honest and self-critical engagement with a

radical period in US history, a bildungsroman of a revolutionary now

behind bars who is not afraid to critique the naivete, or the social

privilege, of his younger self.

While those of us who believe in a

revolutionary break from capitalism cannot endorse Clark’s brainwashed

renunciation, and should never treat the action taken in 1981 as morally

“insane,” we also should be critical of the political strategy behind

this and similar actions. And Gilbert is not afraid to critique the

erroneous line of this strategy (i.e. see the chapter “Foco” as well as

the chapters dealing specifically with actions taken by the WU and other

organizations with which he associated) while maintaining the politics

behind this strategy and the need for revolution.

Nor is Gilbert

afraid of self-criticism [and even has a chapter about

criticism/self-criticism], of harshly examining his actions and beliefs

at different stages of political growth, and so this is not an

autobiography written by someone who wants to hide his mistakes, to

paint himself as an angel. He is quite critical of moments of internal

racism and sexism, of personal errors committed amongst comrades.

The

autobiography proper concludes with the author and his comrades being

imprisoned three decades before he decided to write this book. Only a

small afterword following the last chapter discusses the thirty years

Gilbert has spent incarcerated, but it is telling when read in context

with the political “rehabilitation” of his former comrade: “As my son

approached college age, he became the strongest advocate for my

expressing my sorrow and regrets in a direct and forthright manner—and

I’ve done so publicly on a number of occasions. The colossal social

violence of imperialism does not grant those of us who fight it a free

pass to become callous ourselves. Especially in fighting for a just

cause, we need to take the greatest care to respect life and to minimize

violence as we struggle to end violence. There is no contradiction: I

full-heartedly continue my commitment to the oppressed; I deeply regret

the loss of lives and the pain for those families caused by our actions

on October 20, 1981.”

Whereas Judith Clark’s child was used as

brainwashing method of political rehabilitation, David Gilbert uses the

existence of his son to remind himself that a better world is necessary.

Whereas the political errors made by the actions in 1981 were used to

produce a guilt and shame that would allow Clark to break from her

politics, Gilbert accepts responsibility but refuses to reject a

commitment to the oppressed. And it is Gilbert’s position that liberal

hacks like Tom Robbins will continue to treat as insane and fanatical

unaware that, every time they celebrate comrades who have lost their

way, they are condoning the most insane and violent reality.

(Also: the introduction by Boots Riley from The Coup is awesome.)