By Matt Meyer

WIN Magazine

Winter 2012

The main lesson of “the Sixties,” now passed down through numerous generations, has been that once upon a time there was an amazing period of social, political, cultural, and sexual revolution; too bad most current activists were unfortunately born too late to be involved. That proverbial decade of upheaval—the historic period which began around 1954 and ended late in the 1970s—has had more than its share of written documentation: memoirs, essay collections, and analysis filling whole sections of libraries. Studies of “the Sixties” have become a cottage industry as common as the proverbial “white on rice,” and just about as fulfilling and ethnically diverse.

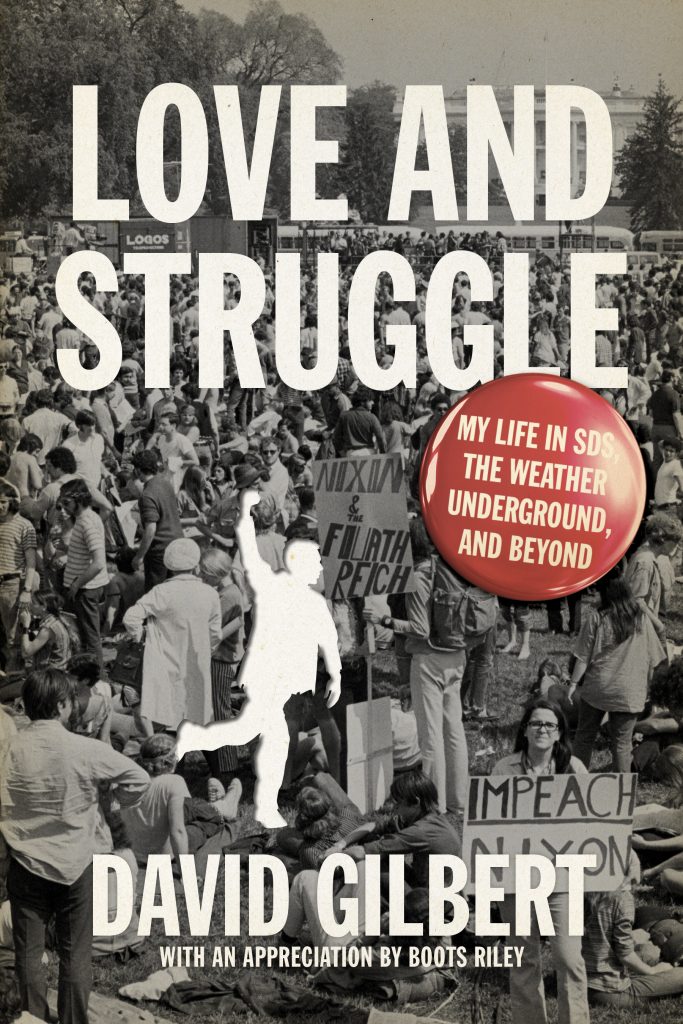

It is therefore especially striking that not one but three new books offer special and significant insights on those turbulent times; each of these titles contain insights which, unlike so many of their predecessors, suggest humble paths for the current struggles-occupations and otherwise. The fact that they each grow out of the context of white anti-war and human rights activities is amongst the only similarity with their countless companions. David Gilbert’s Love and Struggle: My Life in SDS, the Weather Underground, and Beyond (PM Press, 2011), Amy Sonnie and James Tracy’s Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times (Melville House, 2011), and Harry Targ’s Diary of a Heartland Radical (ChangeMaker Publications, 2011) share important insights on combatting racism, building alliances, and designing campaigns based on solidarity and creative linking of issues.

The core weakness of our inter-connected movements-discussed at every Occupation, Social Forum, and networking space where an honest confrontation with “what is to be done” is addressed-is clearly articulated in Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz’ foreword to Hillbilly Nationalists.

“What neither Marx nor the abolitionists nor later leftists and oppressed nationalities in the United States have fully grasped,” she correctly asserts, “is the reality of the United States as a colonizing state in which, as historian William Appleman Williams phrased it, empire has always been a way of life.” The common, vital, and unusual contributions of all three new books is their detailing of how anti-imperialism-in different forms and for different peoples-became a way of life for various white folks struggling to support self-determination for the national liberation struggles which were such a prominent feature of the end of the twentieth century. Sonnie and Tracy use oral history and substantial research to recover an almost-lost history of poor and working class whites who built grassroots organizations in direct solidarity with the Poor People’s Campaign, the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and other local efforts.

Documented in this eminently readable book is the work of Chicago’s Young Patriots Organization and JOIN Community Union (Jobs or Income Now), the October 4th Organization in Philadelphia (named based on a 1779 expropriation of hoarded food and clothing, distributed to the community during the American War of Independence), and the Bronx group known as White Lightening. The late 1960s and early 1970s alliances built by these efforts were, as the authors describe, the first real “rainbow coalitions” for social change across both race and class lines.

Peace studies political scientist Harry Targ has been an institution at Purdue University in Indiana for over four decades. His books and essays have long been essential reading for many movement “insiders,” and/Diary of a Heartland Radical/ happily collects many insightful short reflections on life as a rural-based revolutionary. Less a diary than an assembly of blog posts written since 2008, Targ nonetheless covers some of the fundamental lessons of his years in the struggle, connecting all to the contemporary urgent tasks that still need our committed work. Also focused on the contours of race, class, empire, and resistance, Targ is at his best when he combines his “scientific” thinking with a stridently anti-militarist approach and a good eye for socio-cultural commentary. His point is well taken, as he reviews the early days of the Obama administration, that the Department of Defense—as in the 1960s—has a “blank check,” with academic researchers (now more than ever) providing the data and theories which lead and/or justify disastrous foreign and military policy. The new techniques of “humanitarian” imperialism are explored, as Targ writes about the truly global, growingly privatized, largely antiseptic (weapon delivery through pushing buttons on a computer) nature of twenty-first century empire-building. Targ is also deeply concerned about the strategies and tactics of resistance, evidenced in a wonderful piece on the political economy of the bagel (that Jewish projectile of working class origins) and most significantly in a longer essay on the anti-racist, class struggle history of the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA), another almost-lost part of U.S. left history. Commenting on his own involvement in the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (CCDS), Targ understands that our task is to build as broad a network of progressives as is possible, and his book takes us some meaningful steps in the right direction.

Perhaps the most significant of these new books, however, is Gilbert’s evocative review of his days as a leader of the Columbia University anti-Viet Nam war movement, his days underground with the Weathermen, and his life just before beginning the 75-years-to-life sentence which he is still serving in the prisons of New York State. Love and Struggle pulls no punches-at the movement which led Gilbert to move away from his early commitment to nonviolence or at himself for the consequences of the choices he made. But, more than in any individual, self-aggrandizing life stories found in most autobiographies I have read, Glibert’s reflections are not presented to spotlight or defend his actions, but rather to carefully review the tumultuous times which were a feature of his youth. He dispassionately discusses events he obviously felt passionately about, in order to provide some food for thought to the activists of today. Gilbert’s story, and the book, begins in a context familiar to many of us; his Massachusetts upbringing was in a nice, liberal family where the lessons of “American democracy, with liberty and justice for all” were the cornerstone of his early education. “It sounded beautiful,” Gilbert recalls, “still does.” But he admits that some naiveté must have been at work for him to have “missed the wink” which lets us in on the dirty secret that the “all” referred only to white males with money. “When the myths were later exploded by the eruption of the civil rights movement,” Gilbert writes, “I became deeply upset.”

A common feature amongst Gilbert’s supporters and detractors alike is that he was (and is) one of the much-vaunted “best and the brightest” of his generation. It is of little surprise that he rose to the leadership of Students for a Democratic Society, well-liked by his peers and faculty members alike, praised for his analytic achievement (author of some of SDS’s core pamphlets and positions) as well as for his generous and loving demeanor and organizing abilities. The surprise, therefore-beyond the fact that Gilbert, then and now, maintains a humility uncharacteristic for leaders of those heady times-is that he chose a life not of academic comfort but of on-the-ground street action and revolutionary sacrifice. Throughout the book, Gilbert gives insight into these choices, but none so poignantly as when he reflects upon the common late-1960s question of whether there could be a “revolution in our lifetime.” In the analysis of many in the student movement, Gilbert remembers, “the majority of white people in this country had been deflected from the class struggle by the benefits, the privileges compared relative to Third World people, from the spoils of empire and white supremacy at home.” In reflecting on the idea that the empire’s strengths-global reach and plunder-could now become its weakness (with an over-extended military overseas and a growing resistance movement at home), the notions of hope and possibility are not unlike our own twenty-first century moment today. While Gilbert forthrightly admits to the mistakes which led him and others to costly circumstances, he does so without giving up the sense of hope that social change can and must come through mass political action.

It may seem strange for a magazine committed to revolutionary nonviolence to give a glowing review to Love and Struggle, or any book coming out of the Weather experiment. But Glibert’s basic treatise—that it is “our job is to win large numbers of white people to solidarity with people of the world” in order to create alternatives to “bloody wars” and “less wasteful” lifestyles—is the call to our own critical times. He has forthrightly stated his apologies and regrets, noting that “the colossal social violence of imperialism does not grant those of us who fight it a free pass to become callous ourselves.” Like any true adherent of revolutionary nonviolence (and Gilbert’s life-long friendship with Dave Dellinger gives testimony to this), Gilbert see no contradiction between the need for continued militancy and intensity in fighting against imperialism on the one hand, and, on the other, “the need to take the greatest care to respect life and to minimize violence as we struggle to end violence.” Any humanitarian observer of the United States at this historic juncture must surely see that David Gilbert-and all U.S. political prisoners must immediately be freed if we are, as a people, to arrive at a moment of reconciliation and justice. Any contemporary activist wishing to learn from the exciting achievements (as well as the mistakes) of the 1960s needs to read this essential book.

Noam Chomsky, in his recent acceptance of the 2011 Sydney Peace Foundation prize in Australia, cited the work of A.J. Muste. Reminding us that Muste “deplored the search for peace without justice,” Chomsky re-asserted Muste’s urging that “one must be a revolutionary before one can be a pacifist.” These three important contributions to our understanding of the past and our engagement with the future will undoubtedly help us head their sage advice.

Matt Meyer, WRL ACC member and founding chair of the Peace and Justice Studies Association, is also a founder of the local anti-imperialist collective Resistance in Brooklyn (whose acronym RnB has sometimes been interpreted to stand for the title of this essay). This essay is from the forthcoming issue of WIN Magazine, Winter 2012.