By Puneet Dhaliwal

Ceasefire

May 16th, 2014

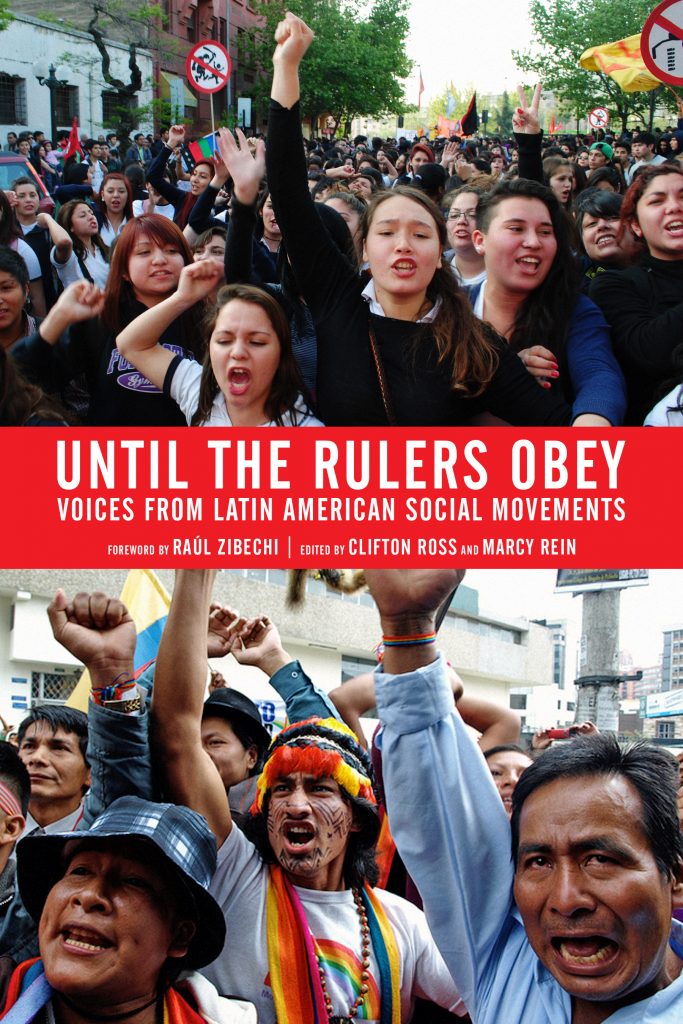

Until the Rulers Obey, a newly published volume edited by Clifton Ross and Marcy Rein, provides an invaluable panorama of Latin America in movement, and should be required reading for all scholars and activists with an interest in the birth of another world in the region, argues Puneet Dhaliwal.

Eduardo Galeano’s 1971 classic Las Venas Abiertas de América Latina (‘Open Veins of Latin America’) — a commanding history of five centuries of plunder, domination, and exploitation of Latin America by European and North American imperialism—closes with a striking note of optimism: in the ever-changing history of humankind, Galeano notes, “every act of destruction meets its response, sooner or later, in an act of creation.”

In Latin America, this latent possibility for creative social transformation is most readily apparent in the upsurge of grassroots social movements that have emerged over the past few decades: the Zapatistas in Chiapas, the Brazilian Landless Workers, and the Argentinian piqueteros, to name a few prominent examples. As well as galvanizing marginalized sectors of society like landless campesinos, women, indigenous communities, students, and the unemployed, such struggles have given considerable impetus to the so-called “Pink Tide” – the wave of leftist and centre-left governments that swept to power across Latin America at the turn of the twenty-first century on the back of popular mobilisation.

Little wonder, then, that many on the left today (particularly activists and writers of the Global North) hold Latin American social movements to be a source of great hope and inspiration for progressive social change in a world deeply shaped by neoliberal globalisation. Moreover, the complex, and often uneasy, interaction between grassroots mobilisation and left-leaning governments has received growing scholarly attention by analysts of the region. The perennial question of how social movements should orient themselves towards, or away from, state power is therefore of central importance to the social transformation of Latin America from below.

Against this backdrop, Until the Rulers Obey—a newly published volume edited by Clifton Ross and Marcy Rein—provides an invaluable panorama of Latin America in movement, weaving together a rich tapestry of grassroots organisations and movements across the region. In a welcome break from dry, academic tracts on Latin American politics, this collection of primary source material and political analysis foregrounds the voices of movement organisers and activists themselves.

The fifteen chapters, arranged by country, begin with introductions from solidarity activists, journalists, and scholars, who briefly sketch the socio-political and economic context in which contemporary Latin American social movements operate. The bulk of each chapter is then devoted to interviews with movement participants, who share their experiences of resistance and perspectives on their movements’ organisational forms and their relation to state power.

While this collection spans a vast array of popular struggles, the chapters share a notable degree of thematic coherence, thanks in no small part to the book’s foreword by Raúl Zibechi, the eminent theorist and long-time observer of Latin American social movements. Tracing the roots of the “new movements” of the region back to popular organisations that emerged in opposition to authoritarian regimes during the 1970s, Zibechi highlights the pivotal role that these new protagonists played in ousting neoliberal governments and altering regional power relations two decades later.

Importantly, these new actors also came to displace a declining union movement as the primary transformative agent and reference point for popular mobilisation in the region. Zibechi thus identifies several distinctive characteristics of the new generation of movements. In terms of their social composition and political character, the movements often accord a significant role to women and families, and emphasise identity and culture as integral parts of their struggles.

Additionally, the emancipatory praxis of the movements presented in Until the Rulers Obey is typically grounded in the collective occupation of (rural and urban) territories, in which self-organising communities affirm their autonomy from state and capital. Such “emancipated territories”, Zibechi notes, may function as sites of resistance to the extraction, expropriation, and dispossession of common wealth—especially land and water—by large multinational corporations. In more constructive terms, these territories in resistance have also become critical sites for the creation of “non-capitalist social relations” through cooperative ventures in healthcare, housing, and education.

The power of the state, of course, remains a fundamental structural force that confronts grassroots movements and threatens to dilute their self-organising power. The editors helpfully accentuate this issue in their introduction by pointing to the demobilising impact of governments’ top-down social policies and attempts to co-opt social movements. To their credit, Ross and Rein also highlight the limitations of autonomous zones themselves, which are vulnerable to state repression, and may be too localised to influence national politics or alter the power of the transnational capitalist class.

On this basis, the editors eschew simplistic binaries between libertarian (anarchist) and Statist (socialist) modes of organisation. Today’s Latin American social movements, they note, display great diversity in organisational models, informed by their “leading-edge experience in successfully tackling the problem of the ‘horizontal-vertical intersect’”. With this conceptual framework in place, the book proceeds to narrate the story of a continent in resistance, told from the submerged perspective of those who are so often rendered voiceless.

Given the breadth of movements surveyed in Until the Rulers Obey, this review cannot possibly do justice to the activists’ wealth of local knowledge, depth of organisational experience, and diverse perspectives on questions of political strategy. Taken together, though, the testimonies of movement participants convey two compelling points that are indispensable for scholars and activists concerned with the democratic transformation of contemporary Latin America.

First, readers will be struck by the thoroughly pluralist nature of the social subjects at the forefront of struggles for radical social change in Latin America today. The restrictive economism of orthodox Marxist guerilla movements has greatly diminished, giving way instead to broader understandings of popular political agency. To be sure, “class” remains a central category, especially for industrial unions and campesino organisations, but class struggle is increasingly interpreted in closer association with marginalised LGBT communities, women who bear the brunt of domestic labour, and long-suffering indigenous peoples.

In particular, the book conveys the critical role that resurgent indigenous movements may have in shaping the future trajectory of the region.

Indigenous communities—for whom the ravaging of local lands by transnational capital is largely a continuation of accumulation processes initiated by conquistadores—have been particularly adept in popularising Indian notions of buen vivir (in contrast with Western paradigms of capitalist development) and local traditions of community autonomy (rather than importing Western Marxist analyses and models of democracy).

Second, and following from the movement participants’ sensitivity to local contexts, Until the Rulers Obey handles questions of political strategy and state power in a relatively nuanced manner that is devoid of what one Argentinian activist describes as the Eurocentric imposition of “cut and paste, one size fits all” organisational models.

Of course, many of the movements surveyed, such as the Zapatistas, are avowedly anti-systemic, and so espouse a grassroots democracy with considerable autonomy from political parties and trade union bureaucracies. Readers, however, will also gain an appreciation of how Latin American movements today increasingly employ autonomism in a highly pragmatic, rather than dogmatic, inflection. Accordingly, some of the most valuable insights to be found in this volume stem from various movement activists who insist on the need to link bottom-up organisation to the radical restructuring of the nation-state, while remaining mindful of the emancipatory limitations of both state socialism and the ostensibly progressive Pink Tide governments.

If all of this seems too obvious, it is worth reminding oneself that many radical theorists, when discussing radical democratic politics in Latin America, all too often elide the sociological complexity of living social movements in favour of ‘neat’ conceptual frameworks. Particularly egregious is the current intellectual vogue of invoking some highly abstract post-structuralist “ontology” of politics and rigidly applying it to particular movements, without so much as engaging in any meaningful social scientific study of the movement in question.

Given the predominance—and blandness—of this common mode of radical theorising, Until the Rulers Obey is a much-needed volume that deserves the attention of any serious observer of Latin American politics. Specialist analysts of the region, of course, may remain dissatisfied with the absence of an overarching framework for understanding the political economy of Latin America and its place within the present global capitalist system. Yet, although the heavily descriptive bent of the chapters somewhat displaces such analyses, the book’s distinctive strength lies in the respect accorded to the perspectives and practices of movement participants, with whom the editors seek to build “deeper and more productive relations of solidarity”. In this context, Until the Rulers Obey is required reading for all scholars and activists with an interest in the birth of another world in Latin America.

Back to Clifton Ross’s Author Page | Back to Marcy Rein’s Author Page