by Dan Carrier

West End Extra

March 8, 2012

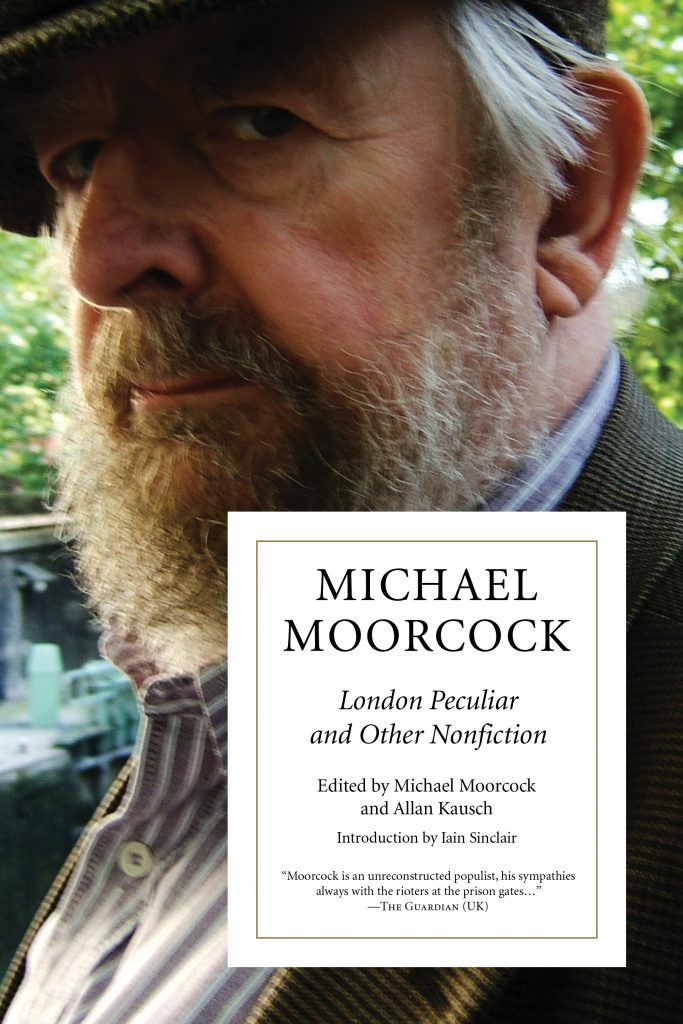

Michael Moorcock is a London landmark who could stand proudly alongside Nelson’s Column and the Albert Memorial, or have a space reserved for him on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth.

The writer, novelist, musician and commentator has a new collection of his works published: essays, diaries, assorted journalism including obituaries and reviews, and general musings on friends, work, books and, above all, the capital in which he grew up.

Moorcock is renowned as a science fiction author and 1960s underground magazine editor—and for playing guitar in the prog-rock band Hawkwind—but his range and breadth is so vast that he sits just as easily at high tables penning think pieces for the Financial Times as he does turning up to talk Martian at American sci-fi conventions.

In his piece, “Heart and Soul of The City,” published in 1990 in the Observer, he wrote of a London he remembered and one that had been swiped away by developers, by weak-minded planners, by the rampant organism of economic growth.

“As a boy I wandered across vast acreages of docks still full of the world’s ships,” he says. “I climbed piles of bombed brick bright with Rosebay Willowherb, the fireweed brought from the slopes of Vesuvius and which took so happily to our ruins.

“If the little foetid canals and waterways under the rotting jetties have given way to dainty fountains and ornamental streams at least we are no longer as likely to die from some nameless toxin as we were when steam was king. For better and for worse, the times as well as the Thames, are changing.”

The Thames reappears in the essay with musing on how it is no longer the reason for the city to exist, rather an appendage to it.

“From what was predominantly a working river, the Thames has become a profitable scenic resource.

“Not very long ago, the GLC built fairly imaginative blocks of flats looking over the water.

World’s End was transformed to give many residents a chance to live with a view instead of a damp problem.

Now the idea of local government wasting such important real estate on its ordinary citizens is received by many pretty as much as [Salman Rushdie’s] The Satanic Verses was received in Bradford.

There is more profit in leisure than in product.

The river is a facility, no longer the reason for London’s existence.

“If, for me, the river has lost some of its romance, it has admittedly lost most of its danger,” he says.

“The dark mysteries of Dickens’s Thames have gone but the benevolent Thames of Jerome K Jerome still exists.”

London comes alive through his pen—a London he says has disappeared and that he now strains to catch glimpses of Sid James sitting on a bus in a Carry On film, or as the backdrop for an Ealing comedy.

He also reveals wonderful confidences with an uncle. “My family opened their homes to the American flyers, some of them friends of my RAF uncle who had disappeared while ferrying a Spitfire in Rhodesia and was disappointed to be found in the bush by rescuers,” he states.

“He hadn’t wanted to be rescued, he admitted to me many years later. He had enjoyed his African Christmases and has several African wives, extraordinary status in the village and no chance of being shot at . . . and his wife, one of my mother’s many powerful sisters, he confided, was a bit if a harridan.”

Music appears: in the article “The Deep Fix,” published in 1994, he writes of Ladbroke Grove in the 1960s and 1970s, recalling Island Records having a studio ten minutes from his house, and how it took on the mantle of Soho in the late 1950s and early 1960s in the London music scene.

“Everybody knew everybody and it was quite often possible to be involved in a session with someone like Charlie Watts on drums, Long John Baldry doing vocals and Pete Green on guitar.

I cut my first demo with EMI in 1957 and it was considered, even by the standards of the day, too dreadful to be released.” Moorcock’s anthology works for numerous reasons, not least the simple fact it is a collection of lovely lines.

Examples abound on every page: “Talbot’s elaborate brass-and-mahogany steampunk paraphernalia constantly add to the visual delights of the tale, demonstrating his mastery of the graphic narrative,” he writes in one book review, while the obituaries he has penned, including one for his close friend the feminist Andrea Dworkin, are simple eulogies.

Of Dworkin he writes the memorable lines: “Even now when I see her picture, I can’t emotionally come to terms with her death. In her most despairing, painful moments her vitality informed all she did and thought.”

He also writes passionately of the loss of his friend Angela Carter, quoting the letter she sent him when she knew she had lung cancer.

It’s a privilege to have such a collection of humanistic and touching articles between the covers of one book.

In the introduction, editor Allan Kausch says: “Compassion and anger can be used against the bastards who enslave us, that the only art that matters is the truth.”

This book illustrates such a sentiment perfectly—Moorcock’s works combine truth, beauty, insight and humour in well-measured portions.

Back to Allan Kauch’s Author Page | Back to Michael Moorcock’s Author Page