By Wenceslao Bruclaga

#VansBookClub

January 15th, 2017

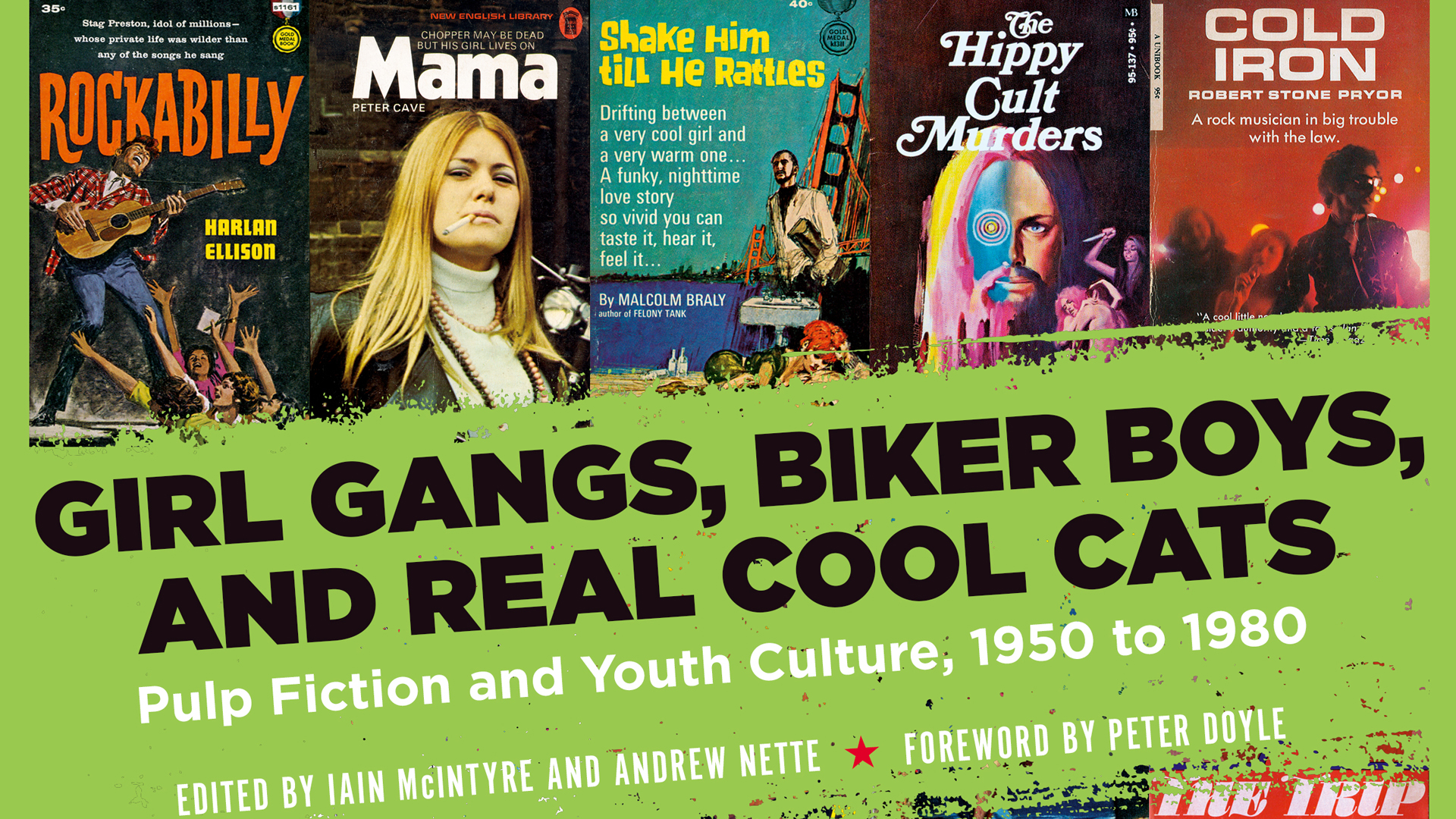

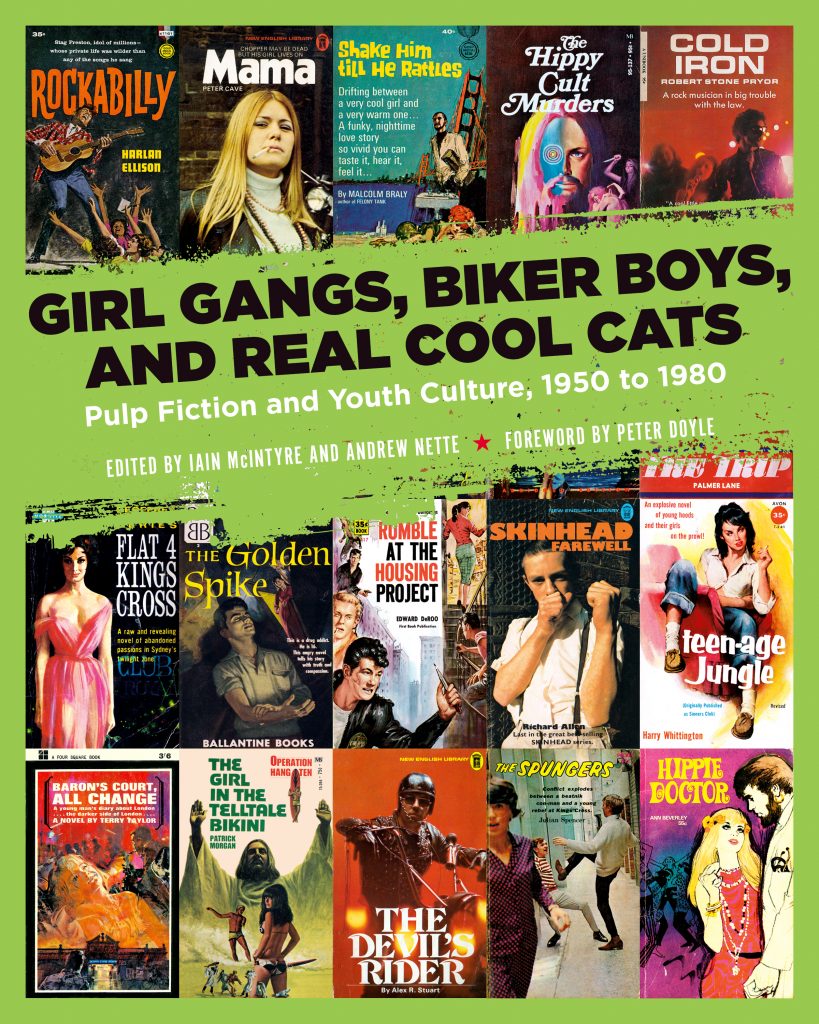

Iain McIntyre and Andre Nette with foreword by Peter Doyle

Live fast, die young and leave a beautiful corpse

If we put ourselves in a postmodern plan, youth as we understand it today is an invention of the twentieth century, such as radio, television, penicillin or MTV.

Before Elvis, youth – the American – was a propaedeutic period for adulthood according to the rules of life then , in which forming a nuclear family, having children and providing the home were signs of success and symptoms of personal fulfillment . The post-adolescent chaos and courtship were lived between the pressure of manners, the heterosexual evangelical persuasion, the sweaty hand and self-censorship. Of course there were debaucheries and slips, but these were enjoyed in secret from good forms, which until before 1950 was the most important thing to survive. Marginality could be worse than being doomed to hanging, at least within the middle-class American dream, which became the consumer social parameter to differentiate men and women from good, outcasts.

Then, Satan became bored with hell and returned to Earth in April 1956, in the form of a defiant molten tuft with Vaseline, leprous lascivious lip and sinful hips, to pump out the hormones of the adolescents in inexplicable boiling; When Elvis Presley made his first appearances on the NBC’s Milton Berle Show, the youngsters discovered that in their inexperiences, as awkward as the first pubic hairs, there was an arsenal of adolescent rebellion, urgent, sensual, insane and most important: causeless.

But Elvis was not a bad example born through the immaculate conception of Lucifer.

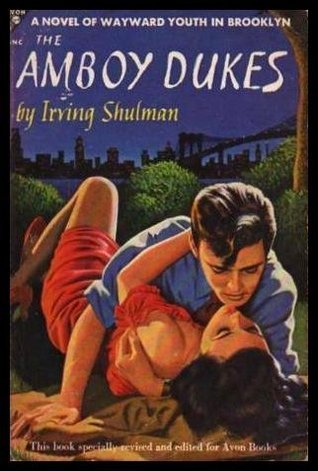

Before there were antecedents that were already beginning to shed adolescent confusion and darkness and that almost inexplicable impulse to conquer and exceed limits even at the cost of their own integrity. Almost ten years before Elvis’ break into popular culture, writer Irving Shulman published The Amboy Dukes , a novel that scandalized post-war gringo society for its crude way of narrating the violent and sexual adventures of young delinquents. Brooklyn, deranging adults and the elderly, in defiance of their ways to tame youth under puritanical pressure lines.

Shulman’s novel marked a drastic change in the overprotective paradigm of the social approach to adolescents, unmasking a series of aberrant behaviors for the vast majority of American society, afraid of seeing their perfect suburbs, as sterile and false as a set of Hollywood of gold, altered by the irruption of young misfits and sadists. Although their stories were fiction, they were inspired by a reality that society preferred to ignore. For readers without risk instincts, trained in great literature or uncomplicated literature, happy endings and cooking recipes, Shulman’s novel was relegated to the so-called pulp literature , which at that time enjoyed a bad reputation, for its low quality, insinuating covers and very cheap paper, almost printed garbage, books for the fucked up and perverts; to see you with a copy of The Amboy Dukes could cost you a visit to the school principal’s office, belts and even visit with the psychologist.

Despite the exile of the prestigious bookstores and with a cost of only 25 cents, The Amboy Dukes would be the germ of a whole youth culture that years later would reap revolutionary phenomena such as beatniks or rock and roll itself. As a curious fact, the name of this novel would be the direct influence for the Detroit proto-metal band who would be baptized in the same way and with a young Ted Nugent in front .

Shulman’s novel reached cult status in record time and long before the term was forged as a historical adjective. The demand was such that the reprints were not enough, returning triumphantly to the bookstores, unmasking the American dream and building youth culture.

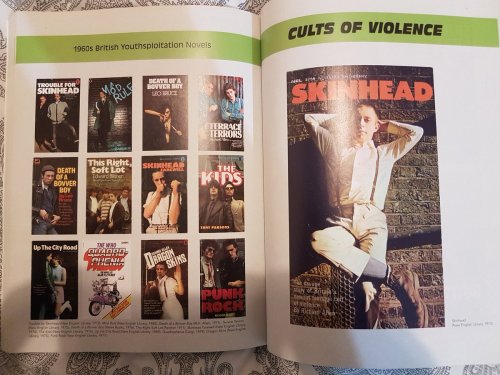

Girl gangs, Biker Boys and Real Cool Cats is a fascinating journalistic and visual historical document, that part of the zero point proposed by Shulman to travel the early years of youth culture seen from the violence and cynicism of pulp literature, or pulp fiction , that shook the good consciences of the United States, England and Australia since 1950 and until the end of the 70s, when pulp probably lost its authenticity to be absorbed by kitsch consumerism.

The punctilious research of its coordinators Iain McEntyre and Andrew Nette over the collaborators of the book is so obsessive, that it reaches moments of epiphany (for the dives) as the first times that words Beatnik (from the books Beatnik Wanton or Through Beatnkis Eyeballs before from the publications of Jack Kerouac), Rockabilly (from the novel by Harlan Ellison considered a great pioneer of juvenile pulp fiction), Hippie ( Happening at San Remo by Bruce Cassiday, A daring novel of today’s young underground -its sexual and mental excesses – its search for sensation and conflict ) or Punk ( The young punks , from Richard Prather to Evan Hunter) appeared for the first time in the vocabulary.

The book, edited by PM Press , also ventures into a risky justice for all that pulp literature that according to collaborators, consider fundamental in movements such as women’s liberation, taking up the novels about gangs of girls or dissatisfied women of disruptive writers like Ann Bannon, Laura del Rivo or Christine James (despised by the feminists of the sixties); or the impulse of journalism and fiction music such as Jazzman in Nudetown by Bob Tralins, The Big Blues by Pal Bunyan, Hard Rock by Jay Lawrence or Second-Hand Family by Richard Parker (perhaps a rough record by Almost Famous) or The Immortal by Walter Ross of the first great biopics or shockumentarys. Taking into account all that delirious pulp literature that took flight with the stories of hippie-satanic cults that would be the breeding ground for gore and soft porn .

An indispensable treatise to know the origins of today’s devout alternative or indie culture.

Back to Iain McIntyre’s Author Page | Back to Andrew Nette’s Author Page