Weird Fiction Review

June 12, 2012

Michael Moorcock is one of the most famed writers and editors in science fiction and fantasy history, a key figure in the British New Wave movement in the ’60s and ’70s, which itself held a strong influence on modern weird fiction.

Moorcock is famed for his stories detailing the adventures of Jerry Cornelius and Elric of Melnibone, among many other acclaimed and award-winning works, and also for his editorship of the British science fiction magazine New Worlds, which published the work of groundbreaking writers such as J.G. Ballard, M. John Harrison, Harlan Ellison, and William Burroughs. In his writing and his editorial work, Moorcock has challenged preconceived notions of speculative literature and often pushed genre writing into fresher, more progressive territory.

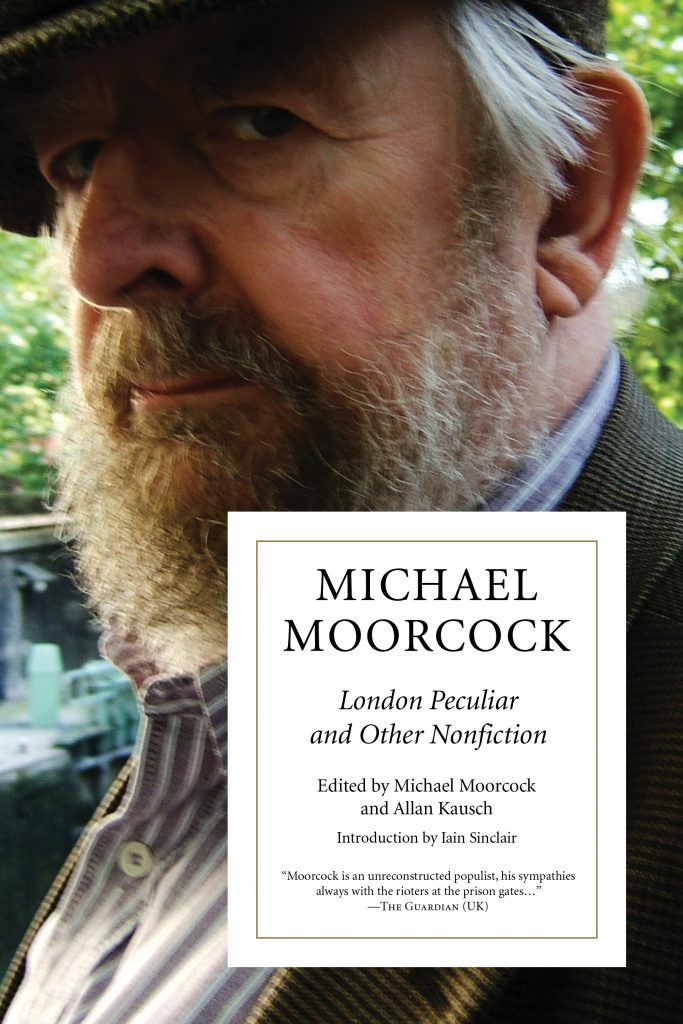

In March of this year, PM Press published a collection of Moorcock’s nonfiction, London Peculiar and Other Nonfiction. Selected from over fifty years of his writing, this collection ranges from recent pieces for the Los Angeles Times and The Guardian to more obscure and – up until now – unattainable work. We’re delighted to reprint an essay from London Peculiar for our readers, courtesy of the author and PM Press: “Breaking Free,” which Moorcock wrote as an introduction to the Klett-Cotta (German) edition of Mervyn Peake’s Titus Alone. Those already familiar with the content of The Weird may recall that Peake’s short story “Same Time, Same Place” is included in that anthology. This essay serves as a sterling example of Moorcock’s nonfiction writing, offering a unique and sympathetic read of an under-appreciated work and a moving eulogy for a master of the Weird. – The Editors

______________________________________***________________________________

In many ways Titus Alone is for me the most interesting of the three books Mervyn Peake wrote concerning the young Lord of Gormenghast, even if it lacks the compelling plot of the first two. For a number of years Titus Alone was considered the weakest because an uncomprehending copy editor cut it to pieces while Peake was in the first stages of the Parkinsonism which would take his life. In its restored form the novel proved far better than critics originally supposed.

If Langdon Jones, the composer, then assistant editor of New Worlds, had not been leafing through Peake’s original manuscript and noticed serious discrepancies between it and the published version, we might never have had the far more complete version. It took Jones the best part of a year, making line by line, page by page examinations of text and manuscripts, to restore the novel as closely as possible to Peake’s original version. The editor had made a bewildering number of unnecessary changes and few would have been capable of the intellectual intensity and powers of concentration displayed by Jones in his great labour of love. Happily, he finished in time for his version to be published in the definitive Penguin ‘Modern Classics’ edition and it is the translation of that which you have here.

Titus Alone

was Peake’s attempt to take his character and method out of the

hermetic world he had created in Gormenghast and Titus Groan and make it

confront not only issues of identity, time and human interaction but

the problems of modernity and even post-modernity—the world as it

emerged from terrible, unprecedented conflict, confronting the Cold War,

nuclear weapons and new forms of authoritarian dictatorship springing

up like weeds from the ruins of the old world. In following this path

Peake recognized the limitations of the form he had developed with such

genius and was consciously seeking a means by which he could expand it

to expose his protagonist to the twentieth century in general and the

second half in particular.

Peake’s instincts were, as always, towards

actuality if not towards realism as it was then understood. In this, he

was perhaps the very first English “magic realist” and an inspiration

to the so-called New Worlds group which saw him, Vian, Kafka, Borges and

William Burroughs as models to emulate in steering imaginative fiction

away from nostalgic escapism and obsession with the supernatural towards

examination of our common psyche and shared experience.

When I first met Peake he was in the last stages of completing Titus Alone.

Both he and his wife Maeve were distracted by the mysterious symptoms

which would be properly identified only after his death. He had already

written his play The Cave, tackling the subject of nuclear war,

and discovered that the majority of people at that time did not want to

examine the issues, certainly in the form he chose. He was depressed

and disappointed in a large public’s lack of interest in his work but at

that point I had no idea what he was going through. On that afternoon

and in the course of many others he gave me far too much of his time and

I fully appreciated his charming generosity. That generosity was to be

his most enduring characteristic. I think it was what also sustained him

through the writing of his great Titus Groan sequence, that wish to

give his readers everything he could imagine and describe.

As the earlier books were dominated by Steerpike, that embodiment of rage against the establishment who, even at his most wicked, still keeps our empathy if not our sympathy, so Titus Alone is dominated by Muzzlehatch, Titus’s mysterious half-mad mentor and guide to the world beyond Gormenghast’s walls. We don’t have quite the same range of comic and grotesque characters here but we do have another cast of gorgeously different women—Juno, who elects to become a kind of guardian, the Black Rose and Cheetah, femme fatale daughter of a wealthy industrialist. But Titus, who scarcely featured in the earlier plots, here begins to come into his own, an innocent, a naïf in comparison to Steerpike. This is far more Titus’s book.

Some readers were originally disappointed not to be given another Gormenghast in Titus Alone and missed the castle’s claustrophobic atmosphere. Muzzlehatch’s vibrant beast of a car, the references to helicopters and other modern inventions, the obvious images reminding us of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp which Peake observed at first hand when sent there as a war artist to record, were not at all what they were hoping for. Some of us welcomed these developments, however, as well as the continuation of the absurdism which is perhaps at its best in the court scene where Titus reveals his father’s fate. This shows Peake working in that great tradition of Sterne, Peacock, Carroll, Lear and Firbank, the same tradition which infuses his nonsense verse and informs so many of his drawings in his Grimm, for instance, and in the most recently published The Sunday Books.

Peake was incapable of resting on his laurels and it is a mark of his genius that he continued to expand his range as a poet, draughtsman and novelist even as that terrible illness, exacerbated by doctors ignorant of the advances we have since made in diseases affecting the brain and nervous system, consumed him.

I saw Peake regularly during those years and was astonished by how rarely his wit deserted him, even when his memory failed. I remember taking the cover proofs of this book to show him at the hospital, knowing that his understanding had almost entirely deserted him. He did not recognise his own work but he did sense that his wife Maeve was distressed. Obviously in an effort to cheer her up, he rose shakily and tried to embrace her. That was the clearest memory I have of his final days, reaching towards his beloved wife and attempting to comfort her, his own work ignored. It remains one of the most moving and significant moments of my life and was typical of his generous nature. His mind had almost completely deserted him, but his humane heart beat as steadily as always.

As it will beat forever, here and through the rest of his magnificently varied work.

Back to Allan Kauch’s Author Page | Back to Michael Moorcock’s Author Page