by Rob Clough

High-Low

January 14th, 2014

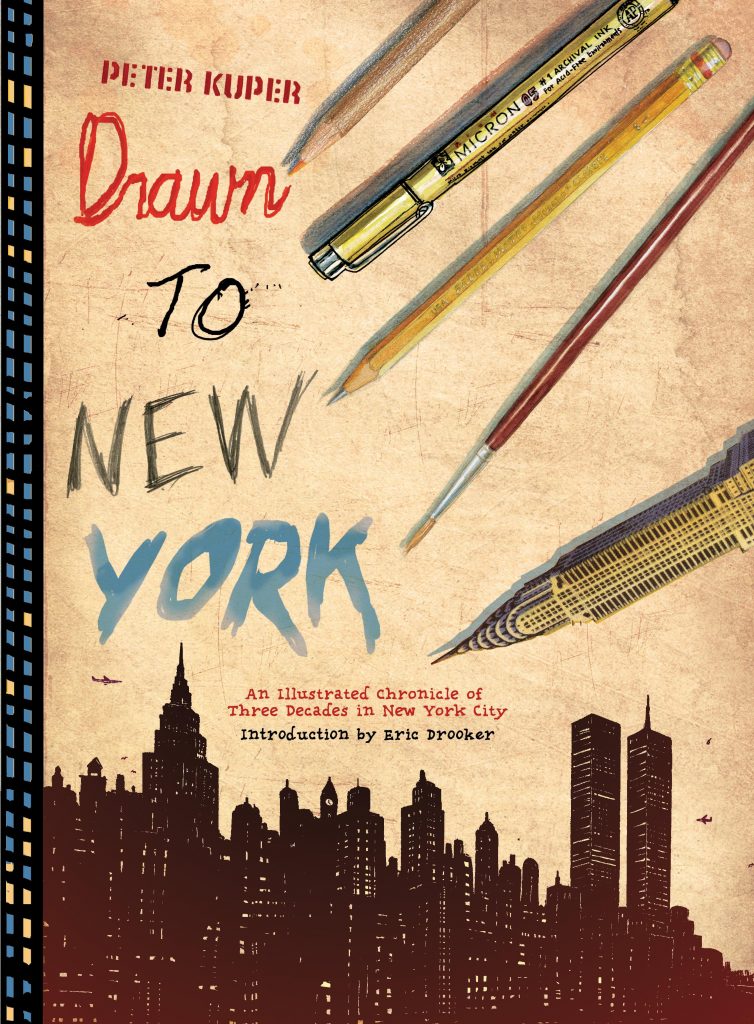

The cover of Peter Kuper’s compendium of New York-related illustrations, short stories and sketches, Drawn To New York (PM Press), reflect the varied approaches by the artist to comic art itself. We see a colored pencil, a Micron pen, a graphite pencil, and a paint brush each spelling out one of the words of the title. It may as well be a snapshot of his toolbox as an artist, because he’s proven to be one of the more versatile and visually dynamic illustrators of the past thirty years or so. The theme of the book is simple, because it’s one of an easily understood contradiction. A Cleveland boy is dazzled by New York upon visiting it and wants to live there. He comes to understand, however, that the city is as squalid as it is spectacular, and his drawings reflect the reality of crushing capitalism against the creative spirit. Despite the forces arrayed against the middle class and poor, he can never quite escape the rush that living in the city brings. That contradiction becomes even sharper post 9/11, when the city suddenly becomes the unwelcome symbol of interventionist US foreign policy.

Kuper has always wielded his artistic weapons as blunt instruments. He has rarely been subtle, whether in his own books or doing strips for the left-leaning World War III Illustrated, which he founded over thirty years ago. His best strips tend to be in the “show, not tell’ category, cleverly letting images dissolve into each other and morph into new but related transformations regarding some essential truth related to poverty and despair, often with a rueful laugh or two thrown in for good measure. He’s especially good at using the city itself to relate cyclical stories, like “One Dollar” detailing what happens to a dollar when it leaves the mint: the lives it’s briefly part of, the pain that’s inflicted just to get it, etc. As always, his jagged figure drawing (inspired in part by street art) is a highlight of any of his strips. “Chains” is a similar strip about the drug trade that pops off the page thanks to his powerful use of colored pencils. “Twenty Four Hours” simply goes through a day in New York City: good, bad, miserable and otherwise, giving the reader a fly’s eye view of what can happen.

On the other hand, his autobio strips about 9/11, while containing a sort of powerful immediacy, don’t quite hold up as well due to the bluntness of his own writing. That said, “Bombed” is fascinating simply because 9/11 was the fulfillment of the horrible daydreams Kuper had had in the form of comic strips about New York getting bombed, buildings being smashed into by planes, etc; the reality wound up being much worse than his fantasies. Speaking of which, “Jungleland” gets at the heart of his feelings about the city: savage beauty, the fear of that beauty being destroyed, and the fear of being destroyed by that beauty.

Throughout the book, Kuper throws example after example of this push-and-pull love and hatred that most New Yorkers feel about their city. There are moments of fleeting beauty, visceral expressions of disgust, extended riffs on decay and corruption, and an understanding of constant and unrelenting change. Kuper depicts a kind of race between the exploiters and the preservers, hoping against hope that the preservers stave off police brutality, the increased divisions between rich and poor, and the potential destruction of the city. Kuper’s aesthetic is a melting pot of influences not unlike the city itself: graffiti, collage, line drawing, paint, etc. His drawings featuring a multitude of different colors in colored pencil are especially lively and tend to represent a free expression of his imagination. The heavy, painted drawings tend to represent doom, distopias and the general sense that the city’s ecosystem is a fragile one, susceptible to extinction at any moment. Kuper seems to view his own role much like Mick Jagger in the Rolling Stones’ song “Street Fightin’ Man”: “What can a poor boy do, but to sing in a rock and roll band?” In his case, what can Kuper do but desperately, ecstatically and compulsively record New York as he sees it? It’s a case of a cartoonist’s blunt style that is limited in terms of nuance being matched up perfectly with its subject: a raucous, energizing, frustrating, depressing bundle of contradictions, a metropolis of codependence, an organism that sustains and feeds on its own.