By David Rosen

CounterPunch

March 30th, 2012

This year, 2012, marks the 200th anniversary of the Luddite uprising, when English textile workers smashed looms with hammers. Few words in the English language invoke such perjorative connotation as Luddite. It signifies the machine breaker, someone who opposed progress and, thus, the capitalist project.

Indeed, the Luddites were machine breakers, they smashed textile looms throughout the English Midlands. Why did they do it? And why, after two centuries of endless denunciation, does their very name still convey such subversive resonance? Why does it still inflame rage among those championing capitalist modernization – and signify hope among the oppressed?

Those with power stamp a certain definition on historical reality, shaping popular consciousness and the meaning of the very words we use. Such is the privilege of power.

A radical critique of power involves a challenge to its definition of commonly-accepted terms of use. Such terms ground socially-shared assumptions or beliefs about the meaning of specific concepts, events and people. These are the terms popularly used to describe and understand social reality. One of these terms is “Luddite,” its original meaning and historical significance long lost to most contemporary users.

Today, two centuries later, the popular struggle against capitalism – a system involving not only commodification and the maximization of profit, but also imperialism, patriarchy, racism, hierarchy and sexual repression – draws inspiration from the Ludities.

For people throughout the world, the Luddites invoke both resistance to injustice and the utopian urge for a better world. This is the world represented by the Garden of Eden, imagined in Thomas More’s 1516 testament, invoked by the Paris Commune and May ‘68, and reimagined today by the Arab Spring, Brazilian peasants, the Occupy movement and still other struggles taking place throughout the world. We are all Luddites!

* * *

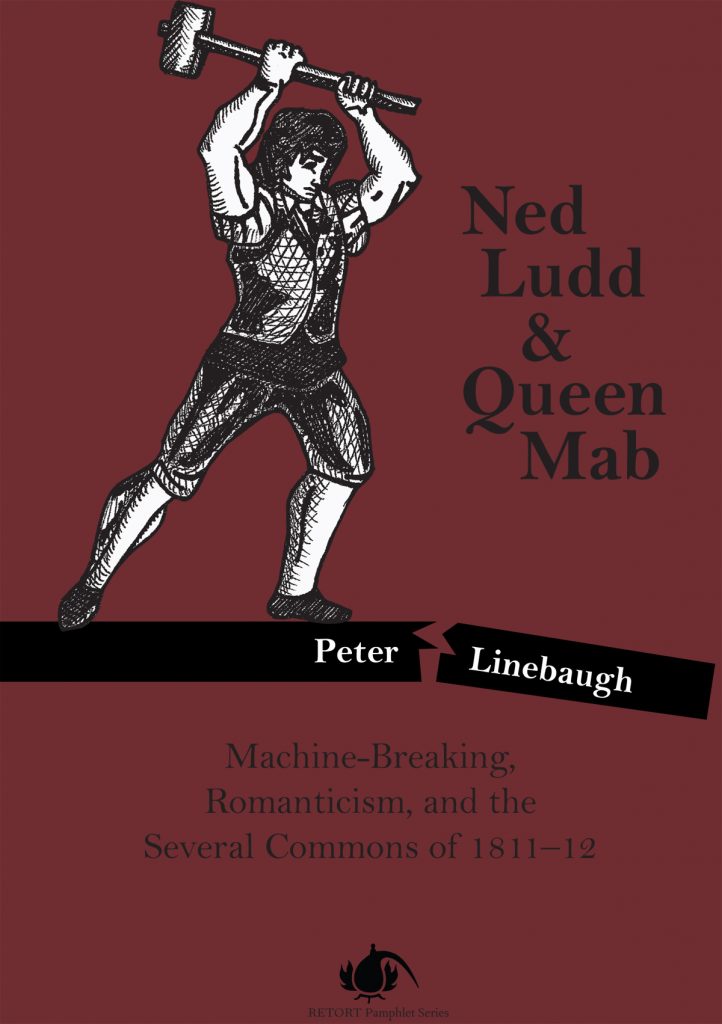

The historian Peter Linebaugh recently published a compelling pamphlet, Ned Ludd & Queen Mab: Machine-Breaking, Romanticism, and the Several Commons of 1811-12. It is a work that links the Luddite battle two centuries ago to struggles taking place around the globe today. It’s a work that connects resistance to the imposition of the earliest stage of capitalism in a single nation-state to confrontations challenging capitalism’s current formation, a 21st century globalized system of plunder.

For all those who might recollect “Ned Ludd,” few will know the reference to “Queen Mab.” Ludd’s renoun is recalled in the word Luddite; Queen Mab is a “philosophic poem” by the great romantic, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Ludd is a mysterious, perhaps mythical, figure, much like Robin Hood. Some say he was born Edward Ludlam and, in 1799, was a weaver who, in reaction to injustice suffered at the hand of his boss, smashed an automated sheering machine with a hammer. His actions inspired fellow downtrodden countrymen a decade later, with textile workers demanding more work and better wage. “General Ludd” led the Army of Redressers. Their campaigns were often broken up, sometimes violently, by British troops.

Shelley was a rebellous soul who lived a parallel existence to the Luddites. When the Luddite uprising took place, he was in Ireland drafting his own version of the Rights of Man. Attuned to the structural changes then remaking England, he – like Lord Byron — questioned the imposition of the new capitalist order. He fully grasped the new system of plunder then in gestation:

Power, like a desolating pestilence,

Pollutes whate’er it touches; and obedience

Bane of all genius, virtue, freedom, truth,

Makes slaves of men, and, of the human frame,

A mechanized automaton.

None should forget that it was his then common-law wife, Mary Godwin, who penned the most resonate novel of the modern age, Frankenstein. Depicting a human creating life, she consecrated the moment when humans became gods. Symbolically, her work marks the end of the pre-history of religious mysticism and inaguration of the tyranny of rationalism, a too-often dehumanizing ethos.

Linebaugh’s linking of these two characters, Ludd and Mab, is a brilliant insight. It acknowledges the unity of practice and theory, of the deed and the idea, of what happens and how it is remembered.

* * *

Wikipedia is a 21st century version of the commons, a monumental site of a collaboratively-created, freely-available and non-commerical information resource. It is an unprecedented accomplishment in world history, one with the great library of Alexandria.

In Wikipedia, the followers of Ned Ludd are defined as follows: “The Luddites were a social movement of 19th-century English textile artisans who protested – often by destroying mechanized looms – against the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution, which they felt were leaving them without work and changing their way of life.”

During the first decades of the 19th century, textile workers in the English Midlands, in the Yorkshire, Lancashire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire districts, said “No!” to the new industrial order. They challenged the new – and oppressive — system of “mass” production and collective employment, the factory, then being imposed on individual workers, often artisans. These hardworking Englishmen knew that the automated loom signified an end to their traditional work and non-work lives.

Between 1811 and 1813, discontent spread throughout a 70-mile swath of northern England. In 1811, Yorkshire croppers, skilled cloth finishers, rebelled against a new shearing system that they feared would put them out of work. In another uprising, in April 1812, approximately 2,000 protesters seized a textile mill near Manchester. In response, authorities fired on the workers, killing 3 and wounding 18.

General Ludd’s army fought against the new industrial tyranny, smashing many of the latest technological innovations, even burning down some factories. In response, the Parliament in London passed the “Frame Breaking Act” that allowed people convicted of machine-breaking to be sentenced to death. To enforce the new law, it sent 12,000 soldiers to put down the Luddite uprising. All told, government forces killed nearly 50 Luddites and, following so-called trials, 24 were executed, 34 were banished to Australia and two-dozen were given long prison terms. General Ludd’s rebellion was suppressed.

* * *

The Luddite rebellion invoked a still-earlier English tradition, the battle against the enclosure of the commons. The closing off of public lands in the 16th century launched the modern agriculture revolution, a revolution that dragged on in England well into the late-17th century. Many Luddities surely knew of these earlier struggles.

The earlier agricultural battles challenged those who sought to privatize the socially-shared commons. The essential English historian, Eric Hobsbawn, famously called these warriors “primitive rebels.” They fought to preserve shared forms of collective exchange and livelihood, especially the public lands, including forests and streams. The commons were essential for their very existence. They lived, not unlike us today, at the cusp of history; for them, it was the world-historic shift from an agricultural to an industrial world order; for us, it’s the restructuring from the post-modern, capitalism dominant in one nation or region, to the globalized – and all digitally mediated — marketplace.

The socially-shared commons united and defined those of rural England as a community; it bound them together as a people. It was, however, being challenged by a new social order based on self-serving privatization, of a new social being, the individual. This is the modern man championed by the English philosopher John Locke – and persists to this day in the Republcian fantasy of masculinity, the slick Hollywood insider, Ronald Reagan. He represented the quintessential patriarchal male hero, a man existing as a pure capitalist commodity.

The Luddites inherited and brought forward the earlier form of collective struggle against the privatization of the commons, of the reduction of the social shared to the individually owned. For people 200 years ago, as for many today, Luddism invokes the desire for a non-commodity human existence, for the self-as-other, for the all-too-human desire for utopia. It is a fight we carry forward today under other names, in the U.S. and throughout the world.

Linebaugh’s links the Luddite insurgency to two intertwined international stories then playing out. One involved England’s wars against Napoleon and against its former colony, the upstart U.S., that culminating in the 1812 burning of the White House. The other story involved uprisings taking place throughout the then-colonized world, including independence movements in Venezuela and Mexico.

Astutely, Linebaugh intertwines these struggles with still other subversive, if localized, battles being fought out in the U.S. One involved the “nigger hoe,” a heavy-duty tool introduced on southern plantations to stop slaves from intentionally breaking farming tools. Another involved resistance by Choctaw, Chickasaw and Creek people in Louisiana to the imposition of the White Man’s plunder of their sacred, natural world. These struggles make clear that the imposition of a new way of life, a new world order, doesn’t come easily.

Linebaugh also emphasizes that capitalism, since its inception, has been a globalizing system of domination … and people everywhere fighting back … and sometimes winning. Today, capitalism is being restructured, shifting from a socio-economic system anchored in various nation states to a globalized enterprise of domination. The geo-political world order is being restructured. And people everywhere are resisting.

* * *

The battle against post-modern enclosure continues the long-fought struggle against privatization and commodification. We witness it in the ongoing global struggles against the corporate expropriation of precious natural resources — oil and gas, mineral wealth (e.g., copper, lithium) and arable lands and water — taking place in South America, Africa, the Arctic … and in the U.S. of A.

In the U.S. today, the enclosure movement involves more than the plunder of oil, gas and coal. It is being fought over everything with the word “public” attached to it. So, schools, prisons, hospitals, water systems, roadways, waste management and even police services are being privatized. Enclosure is also being fought over the extension of private-property copyright control of the human genome and Monsanto’s commodification of the genes for soybeans, corn and other crops. It’s a process that has enriched the rich and made the rest of us pay for it.

Often overlook is how the enabling technology of 21st century capitalism, the digital signal, makes possible the Internet and everything we electronically take for granted, is a terrain of struggle over enclosure. The shift from analog to digital has made the imposition of private-property controls much easier. The digital signal — whether an email message, commercial transaction, phone call, musical selection, pornographic image or Hollywood blockbuster — is just a series of 1s and 0s. Thus, it is easier to monitor, commodify, price and regulate.

Yet, the digital signal’s very simplicity of structure and universality of adoption has made it so easy to innovative upon, but also easy to share, to copy and to hack. Because of its simplicity, digital-based technologies also subvert the push to impose market and government control. This fosters a digital common or Internet underground of hackers and Anonymous as well as mafia scam artists prowling for a sucker. This is the postmodern digital dialectic.

The book, record and home-movie businesses represent one terrain on which the digital dialectic, and thus post-modern enclosure, is playing out. The 1st round of digital innovation was defined by the digital product, whether CD or DVD. During this phase, the corporate media industry both benefited and lost. CD and DVD, cheaper to produce and ship, became the commercial standard, replacing records and VHS videotapes. But CDs and DVDs, like audiotapes, records and home videos, were easy to pirate and still are.

We are in the midst of the second round of digital innovation, the shift from the hardcopy product to an Internet-distributed file. To date, this shift has been spotty, forcing the media industry to repeatedly fine-tune its game plan. File-sharing sites like Napster led to the near-collapse of the century-old record business. But the industry learned and revised its business model.

For centuries, buying a song, book or (much later) movie no longer involves getting a hard copy and putting it on one’s bookshelf or giving it to a friend or library for others to use; this older model is quickly becoming a thing of the past, oh so 20th century.

E-media is cheaper to produce and distribute (no hard-goods or shipping costs), thus potentially more profitable. As people increasingly download copyrighted materials to a Kindle or iPad, they are slowly stopping buying good-old books or magazines, records or movies. The purchasing of a 21st century entertainment product increasingly involves the “licensing” of a work, not its “ownership.”

The licensing of a media work is a form of enclosure, the limiting of “use.” In the 21st digital marketplace, access to an increasingly number of works of intellectual life is being restricted by a number of factors, including often-prohibitive fees to specific devices, to a limit to the number of users with access and to be used for only a set period of time. Postmodern capitalism is replacing quality with quantity, books or songs or movies as digital files. Bleary-eyed online consumers have more choices but less ownership. In fact, ownership is quickly being replaced by a new media rental culture.

(It should not be forgotten that a parallel universe exists online, one that contests the private sales model, whether based on a license or ownership. The most popular examples of this alternative model, one based on sharing, not excluding, are (i) noncommercial sites like Wikipedia and Open Source software and (ii) non-fee, advertising-based sites like Google’s YouTube that aggregates user generated content [UGC].

* * *

Post-modern, 21st century enclosure can be seen in changes restructuring the nation’s communications system. This is the nearly universal digital network that facilitates the distribution of the nation’s – and the world’s – telecommunications. Assuming no glitches, one can make a call or get online and reach someone, anyone anywhere, everywhere in the world in a matter of moments. Americans, 75-years ago, couldn’t have imagined such a world.

Today’s telecommunications regulation is rooted in the 1934 Communications Act. This Act extended Constitutional authority to communication by recognizing telephone companies as “common carriers.” Under the Constitution’s Article I, Section 8, Clause 3, the commerce clause, a common carrier must provide service to the public without discrimination for “public convenience and necessity.”

The American legal system, including the Constitution, was founded during the era when enclosure was remaking not only England but the fledging U.S. The use of the term “common” with “carriers” invokes this history – and reverberates today.

The common-carrier provision was initially applied to railroads, bus lines, trucking companies and other public conveyances. (Ironically, it provided the basis for key civil rights victories during the ‘60s.) The Act was fashioned in an era before digital data and the Internet, thus telephone common-carrier regulation originally applied only to voice messages.

Seventy-five years earlier, in 1860, the Pacific Telegraph Act was enacted. It was the nation’s first legislative effort to establish a neutral communications infrastructure. It stated:

Messages received from any individual, company, or corporation, or from any telegraph lines connecting with this line at either of its termini, shall be impartially transmitted in the order of their reception, excepting that the dispatches of the government shall have priority.

The Act became law during the earliest days of the 1st great media technology revolution, the analog age. This era spanned the century from the first telegraph to the now ebbing era of books, records and over-the-air broadcasting. Can you image someone during the Civil War imaging a world of 1930s telephones, let alone 21st century smartphones and tablets.

The 2nd great media technology revolution, the digital age, begins with the ENIAC vacuum-tube computer in 1946 and looks like it will go on for the foreseeable future. A couple of decades later, the Internet emerges from DARPA. The military-industrial state drives innovation.

Surprising to many, common-carrier regulation did not extend when communications shifted from analog to digital, from voice to data, text and other media. Clinton’s 1996 Telecommunications Act marks when common carriage was privatized. The most glaring example of this process is how the nation’s telecom infrastructure, the Public Switched Telephone Network, was remade from a classic utility, like water or roadways, to a private, for-profit enterprise.

* * *

Media entertainment and Internet services are two terrains on which post-modern enclosure pushes to privatize and commodify all human relations, including those mediated by technology.

The post-modern enclosure movement has extended to wireless and the Internet. In 2007, the FCC reclassified wireless broadband as an “information service,” thus largely freeing it from common-carrier regulation. In 2010, a federal court ruled that FCC common-carrier regulations do not apply to Internet Service Providers (ISPs), the connections that link a person’s computer to the “POP” (point-of-presence) on the web.

This year, AT&T and other wireless providers are further extending post-modern enclosure through the introduction of a new pricing model. Known as “throttling,” it shifts usage plans from “unlimited” usage to pricing tiers based on how much bandwidth a user’s consumes. They make money by closing the digital spigot.

Today, 200 years after the Luddities fought against the imposition of the factory machine in the British Midlands, capitalism continues to intensify the labor process, extend efforts to privatize the public commons while commodifying increasing dimensions of personal life. And the utopian impulse of resistance continues to resurface, whether in Greece or Occupy Wall Street, in the Arab Spring or the Amazon Rain Forest.

In the U.S., this utopian impulse is taking new, clever forms. It was expressed earlier this year in the popular protests promoted by Change.org against corporate greed. One involved a campaign against Bank of America’s effort to impose a $5-per-month fee for debit-card use; it backed down. Another involved an online petition signed by 100,000 people against Verizon Wireless announced plan to charge a $2 “convenience fee” for payments subscribers make over the phone or online with their credit or debit cards; it held off.

Most significantly so far this year, media activists, new-media businesses and ordinary citizens defeated MPAA-pushed “anti-piracy” legislation; in the House it was the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), in the Senate it was PROTECT IP Act (Preventing Real Online Threats to Economic Creativity and Theft of Intellectual Property Act)(PIPA). Most recently, responding to popular protest, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo killed a line-item in the state budget that would have exempted Internet-based phone companies (VoiP like Vonage) from oversight by the state’s Public Service Commission.

Post-modern, 21st century capitalism is a system distinguished by its ability to exploit people as both producers and consumers. As has long been acknowledged, capitalism ceaselessly attempts to impose evermore intense and profitable labor processes on people’s working life, whether at the center or periphery of capital accumulation.

However, the enormous production capabilities of advanced capitalism fostered the great, post-World War II recovery. This period is popularly known as the consumer revolution, but really signified the crisis of over-production. Instead of working less, of shrinking the workweek to 2 or 3 days, thus having fewer things, corporate capitalism remade itself and Americans became consumers. Modern advertising, marketing and the popular media, combined with the credit card, fueled gluttony of both the flesh and the spirit.

To accomplish this, capitalism has fought to crush the social, communitarian impulse, the utopian desire for the commons. Capitalism seeks to reduce all human and natural relations to commodity exchanges. Peter Linebaugh’s inspiring pamphlet places the Luddite struggle within the even older call for utopia. It’s call we need to embrace today more than ever.

David Rosen regularly contributes to AlterNet and Brooklyn Rail; he writes the blog, Media Current, for Filmmaker; and can be reached at [email protected].