The idea that new technologies will replace the need for human labour is not a new one. However, it is currently receiving a lot of attention, following a recent Panorama documentary, and arguments made by figures on the left such as Paul Mason and Yanis Varoufakis.

Sherrl Yanowitz remembers when Rupert Murdoch began his campaign to destroy the print unions. She argues that the battle that followed was not between “an out of date method of working” and new “disruptive technologies”, as Varoufakis has suggested, but between workers fighting for their jobs and a ruthless union-buster determined to break the power of organised labour.

Years before Wapping, we workers on Fleet Street were having meetings about the “New Technology.” I remember a damn fine pamphlet written by Chris Harman, “Is a machine after your job?” in January 1979. We held packed day schools attended by print workers. We were working out ways traditional printers and clerical staff could be trained to use what we then called new technology (computers and so forth).

Many of the manual workers who sweated all day setting ‘hot metal’ would have been quite happy to retrain to easier less physically demanding practices.

In the mid-1980s Rupert Murdoch built a ‘secret’ alternative printing plant out in the East End while pretending to negotiate pay and conditions with all the traditional print unions. High up officials within the Electricians union (without the knowledge of the rank file print and building worker electricians) helped Murdoch recruit an entirely Scab substitute workforce.

Murdoch owned News International, the holding company that owned and ran the Times, the Sunday Times, the Sun and The News of the World. There were more than 6,000 employed by News International, including not just ‘printers’ and ancillary workers, but clerical staff, library staff, telephonists, canteen workers, sub editors, journalists and distribution workers.

We were manoeuvred into an all-out strike on Friday, 20 January 1986. On Monday morning 23 January, almost every one of us received Special Delivery letters summarily firing us. Even people in hospital on sick or on maternity leave received these letters. The whole thing was an enormous trap that all 6,000 of us fell into.

I was a very newly elected secretarial rep on the Joint Clerical Chapels Liaison Committee. On the very first Wednesday of the strike we called a spontaneous demonstration from Tower Hill Tube Station along the Highway to the Wapping Plant. Our Print Union officials were scared of what we might creatively get up to, and quickly turned our demonstrations into set piece demos every Wednesday and Saturday night. All the time, week in week out, quite literally in freezing sleet or blistering heat, for almost 13 months we stayed out on strike.

We weren’t fighting to defend what people like Yanis Varoufakis have called failing old methods, we were fighting for the jobs of 6,000 workers. But we were not fighting for just those workers’ jobs but those who might be the next people to take those jobs. And fighting for the future jobs of all 40,000 print workers in and around Fleet.

But that wasn’t all. I recall addressing a fringe meeting at the National Union of Journalists conference. It was late in the day for our dispute and I was quite very blunt. I told them to fight to save our jobs and fight to call out the whole of Fleet Street in our support, or there wouldn’t be any NUJ to speak of in a few years. The room went very quiet.

Sadly I was right.

Further reading:

- Chris Harman’s pamphlet, transcribed on marxists.org.

- This recent article in Jacobin Magazine that drew on ideas from Harman’s pamphlet.

On the original Luddites, textile workers, who smashed looms in protest against forced industrialisation in the early 19th century, see:

- P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963),in which Thompson set out “to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the “obsolete” hand-loom weaver, the “utopian” artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity.”

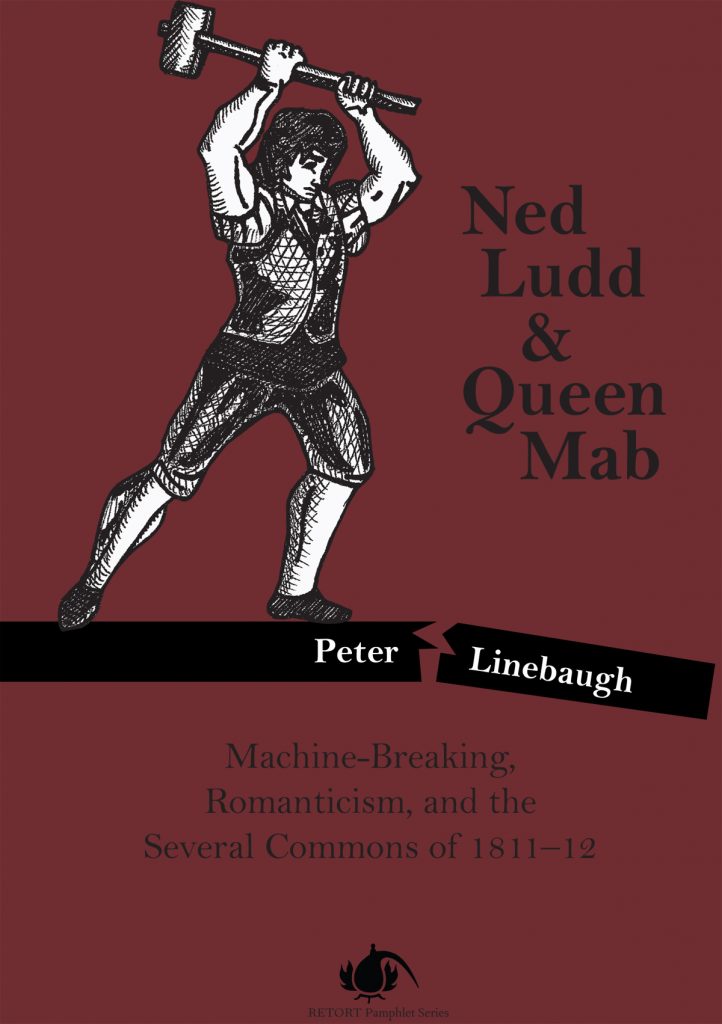

- Peter Linebaugh’s Ned Ludd & Queen Mab: Machine-Breaking, Romanticism, and the Several Commons of 1811 – 12 (2012)written on the 200th anniversary of the revolt. Here is a recording of the lecture that Linebaugh’s book was originally based on.