The Anvil

February 19, 2012

We

could create change and resist the destruction that they wrought on the

world. I felt joy and hope in all the possibilities we could continue

to create, rebelling against their hallowed message that we should give

up and give in.

I had to climb the hillside to see what was on the other side.

Once

I did, I saw the giants everywhere. I continued onward with curiosity

and courage. I saw others doing the same and many of us walked together

in mutual support (42).

From Rousseau’s infamous noble savage to a

fascination with tourism, western capitalist society has found many

ways to both maintain and exploit the image of some people as Other. One

of the more pernicious flavors of this is to see some people as more

authentic, more in touch with their humanity and their experience. This

increased authenticity can be attributed because they have suffered

more, or because they are not seen as fitting into the model of the

Normal Person ™ (who is supposed to be some combination of [sub]urban,

white, middle class, straight, certified sane, etc). A particular kind

of interest in folk art is part of this alienation.

In Europe,

psychiatric collections, mediumistic art work, and paintings by

autodidacts such as Alfred Wallis (1885-1942) and Henri “le Douanier”

Rousseau (1844-1910) were held aloft by modernists, along with colonial

plunder from Africa and the Americas as salvation from

industrialization’s increasing ravages (Gale 1999:16 and 17). Across the

Atlantic, a similar fascination with “naive” expression was taking

place. Championing the romanticized notion of a fast-fading authenticity

inherent in Anglicized American heritage, certain collectors, scholars,

gallerists, and museum professionals turned their attentions to folk

traditions.

The definition for folk art is quite contested:

how is it distinct from crafts (or is it)? What is its relationship to

fine art and schools of art and art schools? Must it be completely

untouched by the art market, or can folk pieces be in dialog with fine

art pieces? Can fine artists do folk art? Should folk art be an umbrella

term that includes naïve art, art brut1, tribal art, tramp art,

self-taught art, etc, or is it a thing distinct from any of those? And

so on.

For our purposes, wikipedia gives a reasonable entry:

Folk art

a)

encompasses art produced from an indigenous culture or by peasants or

other laboring tradespeople. In contrast to fine art, folk art is

primarily utilitarian and decorative rather than purely aesthetic

b)

expresses cultural identity by conveying shared community values and

aesthetics. It encompasses a range of utilitarian and decorative media

and

c) is practiced by people who have traditionally learned

skills and techniques through apprenticeships in informal community

settings, though they may also be formally educated

As with all

attempts to define a group as outside of capitalist, western, urban

values or experience, this can be read optimistically (the definers are

dissatisfied with the status quo and are reaching for something, trying

to understand the world in different ways), or pessimistically (the

definers are attempting to integrate all difference into the status quo,

to flatten differences even while they trumpet how “different” they

are).2 More to the point, the members of the given group are both inside

themselves and outside themselves at the same time. The Situationists

were brilliant in their analysis of the Spectacle as something that

divorces people from our own experience, an alienation that we are all

subject to, but that members of Otherized groups are subject to

differently. Vine Deloria’s article “Anthropologists and Other Friends”

is intense and paradigm-shattering in its depiction of the relationship

between anthropologists and the people-being-defined, negating (among

other things) the idea that any of us can be untouched by the society

that envelopes us.

Organizations like the National Endowment for

the Arts rightfully define folk art as art coming out of a specifically

identifiable tradition. Folk art is “learned at the knee” and passed

from generation to generation, or through established cultural community

traditions, like Hopi Native Americans making Kachina dolls, sailors

making macramé, and the Amish making hex signs. From the website for the

American Visionary Art Museum

Hopi-Native-Americans-making-Kachina-dolls (et al) are not just involved

in a deeply spiritual and practical effort that their people have done

for generations, they are also operating as Authentic Others within a

capitalist model. These two ways of existing are diametrically opposed –

are even mutually exclusive—and yet this paradox is embodied in these

Hopi (et al), and to varying degrees in all of us.

Our truck sped

along the highway, our thoughts in a tumult. Few cars moved our way,

apart from the occasional military vehicle. In the other direction, the

roadway was overflowing with evacuees. They began to look like refugees

from another place (45).

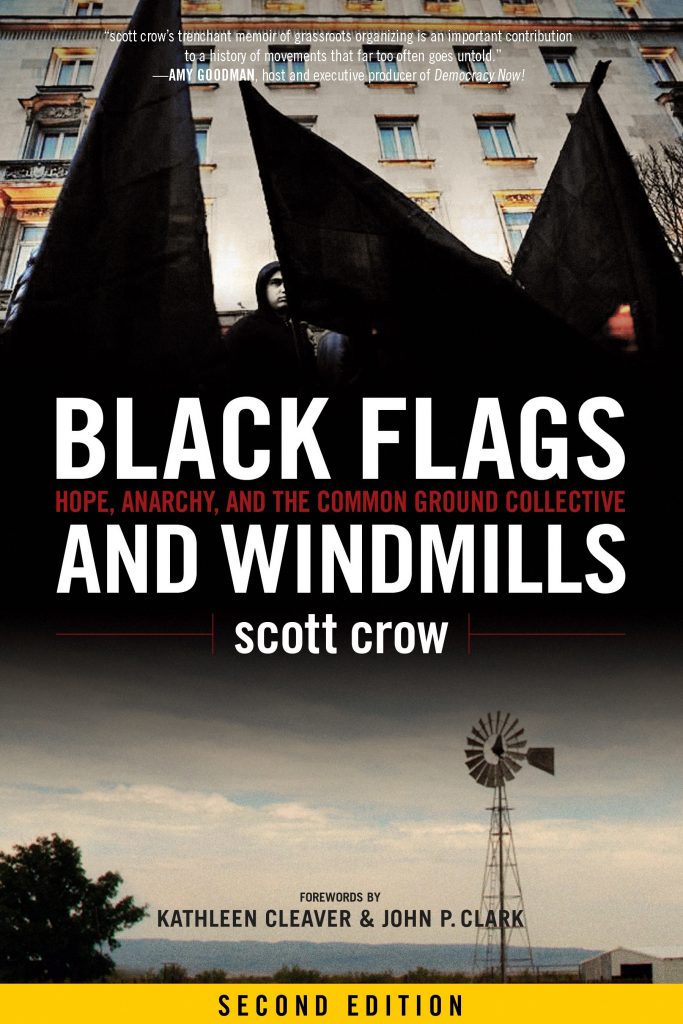

In Black Flags and Windmills (BF&W),

scott crow—the best known (or at least the most interviewed) of the

founding members of Common Ground Collective (CGC)—explains how he grew

up and in to a world view that promotes a certain way of looking at

race, class, disenfranchisement, responsibility, and privilege. BF&W

is a reflection of that world view—one that has been called variously

anti-racist, anti-colonialist, leftist—with many of its strengths and

weaknesses.

While the group had many contributors and

co-creators, it is fair to say that CGC (now a non-profit called Common

Ground Relief) was initiated by a local ex Black Panther, a local woman,

and an anarchist, in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, when

New Orleans was traumatized; entire neighborhoods had been

emptied—sometimes through force; the government was demonstrably more

interested in controlling the behavior of those who were left, than it

was in meeting their needs. CGC, like many other efforts that seek to

serve people’s needs without government or NGO mediation, has been

lauded by some as an example of direct action, and criticized by some as

a charity. In fact it was probably both, depending on when and on which

people or subset of people one focuses on. Scott crow makes clear that

there was an ongoing negotiation between working with people who were

not anarchists, not used to dealing with anarchist horizontal process

and mostly probably not interested in learning to deal with it, and the

anarchists who made up most or sometimes all of the volunteers who were

coming in from outside the area. Differences that were not made any less

challenging by the different racial, economic, and cultural

compositions of the two groups.

Naïve art:

The main

characteristic of naïve art is a rejection, or strained relationship to,

the formal qualities of painting, especially the three rules of

perspective (as defined by painters of the Renaissance):

The rules of perspective are

1. decrease of the size of objects proportionally at distance,

2. enfeeblement of colors with distance,

3. decrease of the precision of details with distance.

The

lack of these characteristics leads to an equal accuracy brought to

details, including those of the background, which would be shaded off in

fine art paintings.

BF&W is an exercise in folk and naïve

art, because it is less a cohesive story (or even set of stories) than a

record of part of a conversation. The book does not abide by any of the

rules normal for books on any of the themes that it includes. It is

more than a memoir of CGC (it includes some of scott crow’s childhood)

but less than an autobiography—crow mostly discusses his childhood,

political development, and part of his life during the existence of CGC.

It includes a history lesson but only for a few disconnected and very

specific pieces of history, without a larger context (primarily the

Black Panthers and the Zapatistas). It is a political text by an

anarchist who seems to have been most inspired by non-anarchists. It is a

manual for disaster relief without much step by step information to

duplicate specific success(es). It is an adventure story about fighting

cops, vigilantes, snitches, and entitlement, as well as surviving the

environment, without a clear ending. People who already know a bit about

CGC might read this book for more information on Brandon Darby, who was

a significant part of the story for scott crow, and who gained

notoriety first from to his self aggrandizement, and later when he came

out as an informant to the FBI. However, where scott crow discusses

Darby, it has more to do with crow’s process of coming to terms with the

fullness of Darby’s perfidity, than it does with an analysis or

accounting of Darby’s behavior.

More fundamentally, the text does

not follow a single line at any point. All of the threads are woven

together in the way that spoken conversations sometimes flow, but that

seem quite random on paper. Because there are so many threads that all

seem to get equivalent attention, it’s hard to know which is foreground

and what background.

This conversational style, in which bits

from all the various themes are mixed together–biographical fragments

with stories about the Spanish Civil War and crow’s alliances with

ex-Black Panthers (a description that is featured heavily throughout the

book), etc–is so pronounced that it makes the book seem like something

new, perhaps a book that is for people who don’t read, who don’t like or

want to be limited by the patterns or habits in more traditional books.

So

Folk as a description operates here in two ways. First is that of “a

set of practices learned by watching other people,” in the sense that

crow learned his activism by watching and listening to ex-Black

Panthers, and from them received a particular take on identity, society,

and liberation that he faithfully represents here, even when it is in

conflict with much of anarchist thought. In a chapter called Of

Anarchists, Panthers, and Zapatistas, crow explains his own eventual

embrace of the label anarchist (after rejecting it initially because of

his distaste for punk anarchists in his youth), when he decided “it was

time to shock the political system.” For some it will be odd that in

this chapter the examples of actual action that he uses are two groups

that have no anarchist affiliation at all.

It is not hard to find

criticism of the authoritarian practices of many within the Black

Panther Party; one example is this quotation from Paul Glavin’s friendly

review of Liberation, Imagination, and the Black Panther Party (edited by Kathleen Cleaver—who wrote the preface to BG&W—and George Katsiaficas).

The

authoritarian, top-down structure of the Panthers, combined with their

reliance on Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, is objectionable from an

anti-authoritarian perspective. The Panthers saw themselves as a

vanguard Marxist-Leninist style Party with hierarchical ranks and they

were influenced by Mao. For example, Michael L. Clemons and Charles E.

Jones’s essay, “Global Solidarity,” points out that fifty percent of BPP

political education classes were devoted to Mao’s Little Red Book. Key

members were given State titles, such as Minister of Information and

Minister of Defense.

In this collection, Mumia argues it is hard

to generalize about the BPP because it had many offices and a diverse

membership reflecting regional and cultural differences. Yet by the

1970s the BPP did become increasingly authoritarian and centralized

(http://www.newformulation.org/1pantherinsurgency.htm).

And the

Zapatistas, as exciting as they have been for people looking to create

mass movements, are themselves not even anti-state.

The EZLN has

not hidden their agenda. Their aims are clear already in the declaration

of war that they issued at the time of the 1994 uprising, and not only

are those aims not anarchist; they are not even revolutionary. In this

declaration, nationalist language reinforced the implications of the

army’s name. Stating: “We are the inheritors of the true builders of our

nation”, they go on to call upon the constitutional right of the people

to “alter or modify their form of government.” They speak repeatedly of

the “right to freely and democratically elect political

representatives” and “administrative authorities”. And the goals for

which they struggle are “work, land, housing , food, health care,

education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice and peace.” In

other words nothing concrete that could not be provided by capitalism.

Nothing in any later statement from this prolific organization has

changed this fundamentally reformist program. Instead the EZLN calls for

dialogue and negotiation, declaring their willingness to accept signs

of good faith from the Mexican government.

From THE EZLN IS NOT ANARCHIST

crow’s

book exemplifies a conundrum for a particular kind of anti-racist

activist, which is the question of how much one constrains their ideas

to fit into models that have been approved by people of color. When one

is an activist, as crow decidedly is, the models of the panthers and the

zapatistas are too practical and successful (within limits) to be

denied. But if anarchy is something more than a set of tactics, then one

must admit that anarchy is impractical. It is not practical to have a

beautiful vision of the potential in all of us, a potential that demands

the overthrow of so much that so many take for granted or in fact

demand. This dilemma continues to be acted out in many people’s

political activities and organizations, and the scott crow book is

(among other things) a story of the balancing that he was trying to do

between its horns. “Anarchism means not waiting for the other to do

something. It means knowing what the right thing to do is, recognizing

we have the power to do it, then doing it” (73).

But Folk can

also apply to the way that a work is understood to be outside of

institutions; counter to what is considered learned or erudite; easy for

the Common Folk to understand.

When the point of a work is to

replicate cultural norms that are not scholastic or outside of a

particular form-of-life, to be—for example—accessible to a group of

people who are not used to reading, then the conversational flow and

familiar language will be a comfort and an encouragement. These might be

the people who take the story of Don Quixote’s windmills as an

expression of hope and a refusal to concede, rather than as a sign of an

old man’s delusion.

Reading this book brought up for me questions of habit and form, formality and structure.

Arguably,

scott crow took the format—papers bound together with glue and a

cover—and made it his own. A practice that egoists, among others, might

be able to appreciate.

1. aka outsider or visionary art—i.e. art by people who are considered insane or far outside of social convention)

2. Of course both pessimistic and optimistic views are true simultaneously.