by Blair Parsons

Texas Observer

September 16, 2011

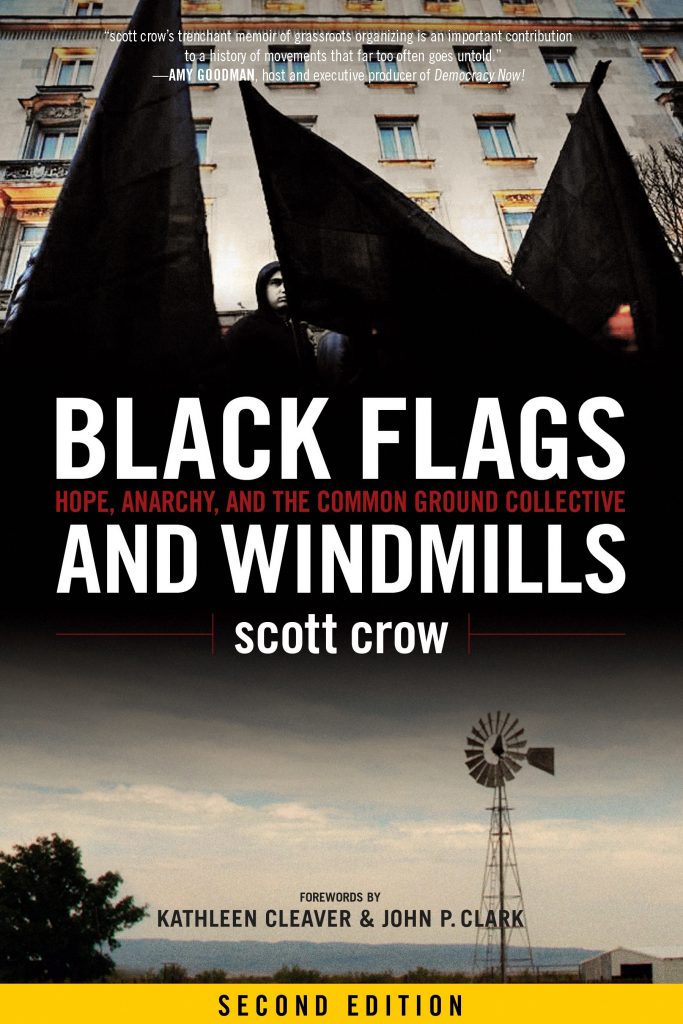

Black Flags & Windmills: Hope, Anarchy & the Common Ground Collective by Scott Crow

Ann Richards folded clothes in the corner. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina thousand of evacuees arrived at the Austin Convention Center. Volunteers arrived as well, running a makeshift cafeteria, constructing shower facilities, and sorting donations. From my workstation I watched Ann Richards fold clothes on the other side of a large pile. Her work conveyed an affirmation of dignity. She seemed to recognize that no one who has lost so much should have to pick clothes from a pile. He should be afforded the dignity to select from folded clothes.

A man who spoke with enough authority to claim it told me we needed Governor Richard’s table for another project. I was told to get it from her. I approached her and let her know what was needed. She smiled, held up a tiny pair of pants, and said, “you find a man that can fit in these jeans and this table is yours.” Awestruck and incapable of deciding whether to laugh or bow, I mumbled a thank you and took the table. Her humor reaffirmed dignity.

Like many folks after Katrina hit I wondered about the best way to help. After briefly considering going to New Orleans, I decided to stay in Austin. Katrina closed the gap between the two cities and thousands of evacuees needed assistance in Austin. Fair or not, I felt I would end up in the way in New Orleans. Others decided to go.

Scott Crow went and recounts his experiences and work in Black Flags & Windmills: Hope, Anarchy & the Common Ground Collective. He initially went to rescue a friend incommunicado since the storm hit. Once there Crow quickly realized the vastness of devastation coupled with the inefficiencies of the nascent relief mission that would hamstring the region. Crow, a seasoned organizer, harvested old connections and established new ones to begin relief work in Algiers, Louisiana. This initial work developed into the Common Ground Collective, a horizontally-aligned, community-run collective responsible for assisting thousands of people through food distribution, medical assistance, mold remediation, and security which was vital as the power vacuum became unstably vacant in Katrina’s aftermath.

While Common Ground took shape the vacuum began to fill with a volatile cocktail of greed, racism, and fear. Some members of Common Ground took up arms to protect themselves and their community, knowing their work could not flourish without security. I have never brandished a weapon, but neither have I had one pointed at me. Right or wrong, Common Ground decided guns were a necessary response. Throughout this tenuous time, Common Ground’s commitment and work remained unshaken. Undaunted by constant security threats, the collective remained steadfast. Crow writes “we would not let Power deny dignity and self-determination to anyone.”

Like any great experiment, the collective experienced conflicting egos and philosophies. A united organization operating often in defiance of federal officials would have a difficult enough time. Introduce varied political prisms and the situation becomes arguably untenable. Common Ground melded Black Panther theory, anarchism, and other assorted influences, but the melding was not seamless. Concerning the ability to convey foundational principles throughout the collective, Crow writes “It was easier to communicate these ideas and values when our numbers were smaller.” As the collective grew exclusion developed.

For the folks who received relief from Common Ground, the political makeup of the organization mattered little. What mattered is that aid came. Crow’s selflessness enabled almost around-the-clock work, but his rigidity led to condemnation of those outside his framework. Drawing too many lines in the sand leads to isolation. He writes frequently about analysis. His is black and white. With us or against us. Crow uses divisive statements like “they had no principles” and “they were comfortable with the status quo.”

He writes, “the military were not there to protect and serve; they were there to do whatever they wanted with impunity…they had followed orders all their lives. When their command structure broke down, they had a chance to do something different, to side with the people. They chose intimidation and brute force.” This situation undoubtedly happened in cases, but to deliver such a broad condemnation is an overreaching generalization. As evident from the book, Crow had terrible experiences with military personnel, but that does not mean all military personnel became lawless rogues. Despite his rigid analysis, Crow does marvel at the myriad folks involved with Common Ground and the greater New Orleans region.

Perhaps Katrina required black and white, because only a zealot can keep going with the odds so firmly stacked against him. Crow’s dogged persistence helped establish and run an organization that aided thousands despite bureaucratic red tape and limited resources. Common Ground did not build Shangri-La, but it accomplished something extraordinary. It brought relief, picked pride up from the ground, and ensured a community would weather the storm. Common Ground empowered volunteers and residents. Crow encapsulates the spirit of Common Ground, writing, “Our revolution challenged the standard pessimism about people’s limited agency in their lives.”

Katrina was a galvanizer. We watched horrific images of a region underwater and struggled with what we could do. After the initial shock and confusion, folks got busy doing what they could. Some donated money. Some folded clothes. Some hopped in trucks and left for New Orleans. The relief effort’s enormity demanded any kind of aid, so a strange beauty arose from the empowerment of each individual response, but only a physical presence can convey supreme solidarity.

Crow remains an advocate of solidarity over charity. In differentiating the two approaches he writes “Solidarity, on the other hand, is the view that service work is a support to those directly affected by injustice, aiding them in taking charge of their lives. Solidarity aims to solve the deep-rooted issues. Solidarity links us together across geography, economics, culture and power. It is more than dressing a wound; it allows all involved to be participants.” Scott Crow and Common Ground were there with their hearts, bodies, and ideas hell-bent on making a little place in need a better place.