by Nathan Diebenow

Diebenow.com

November 2011

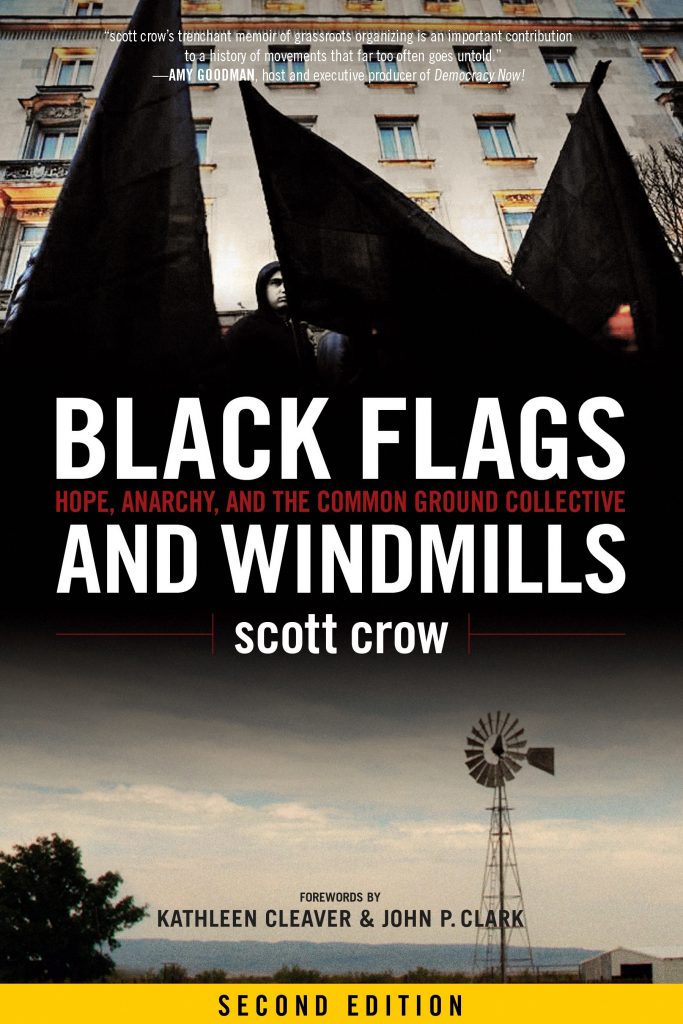

It’s

not everyday that you get to hang out with a someone who toured with

Trent Reznor, or someone who co-organized the largest

anarchist-influenced organization in modern American history, or even

someone whom the FBI labeled a “domestic terrorist.” But the good folks

of Occupy Denton (Texas) and I had the opportunity to interact with all

three of these someones in the form of one scott crow this time last

month.

You might have heard of the FBI’s shenanigans against

crow and his friends from the New York Times in May or from Democracy

Now in June or from Rag Radio in August.

But if you haven’t

heard it, I highly recommend his Rag Radio interview not only because

crow speaks more on alternative economic systems but also because played

are clips of the political industrial dance music he co-created with

his former group Lesson Seven in Dallas in the late ’80s.

Had you

sat in on crow’s talk at Occupy Denton, you would have received a more

in-depth look at the last 20 years of his experiences organizing

communities—such as those at the University of North Texas (UNT) in the

anti-apartheid movement to those in New Orleans days after Hurricane

Katrina threw the gross racial and wealth inequalities of the region in

the face of the One Percent.

Because of the horrific police

actions against Occupy Oakland when veteran Scott Olson received serious

brain injuries on Oct. 25 following a general feeling among some

occupiers that the cops are also part of the 99 Percent, I intended to

speak with Crow about the Occupy movement’s relation to the State.

Thankfully, he also occupied the conversation toward the nature of

social movements and the history of previous organizing efforts that led

to the Occupy movement’s structure.

Here is the fruit of our 10-minute discussion after his talk at Occupy Denton on the UNT campus off Fry Street, tents and all:

…………

Diebenow: What

do you think about the “Occupy Police” wing of Occupy movement on

Facebook and Twitter? Are you skeptical about the solidarity that this

group espouses? Or are you hopeful that it will break the bubble that

surrounds the police?

crow: I’m absolutely

skeptical of that because one, the Occupy movement is super

decentralized. There’s no one voice in that. Anybody who purports to

speak for all the Occupy movements going on is total bullshit. Secondly,

I think one of the things we have to realize in this country is that

the police, like a lot of wealthy people who may be interested in what’s

going on, are never going to join these movements until it effects them

directly. People in upper middle class strata, like very upper middle

class strata at the top of the 99 Percent who feel like they don’t feel a

part of it, and the police, until it effects their bottom line, until

the banks are closed, until the ATMs are not working, until their checks

aren’t coming, their pensions are gon, then they will join the

movement. But the police are never going to side with us until that

happens. The police are paid to uphold private property of corporations,

corporations, and the state. That’s their job. I mean, that’s their

mandate. Given the order to shoot me, they’re going to do it. Is that

dramatic enough? (laughs) But it’s true.

Diebenow: What

you just described to me is basically like if you see any of those

things happening, you’ll be less skeptical. I mean, we’re talking

system-wide.

crow: Absolutely. Listen, there are

individual good cops. I’m not going to lie. I mean, I’ve dealt with

lots of them over the years, but I know ultimately their job—their

job—what they get paid for day-in and day-out—is to uphold the state.

They have loyalty to that whether they want to or not. They have

families to feed. They’re on a wheel, like a gerble wheel or a hampster

wheel, and they’re spinning in that. They are part of the system as much

as anybody is. They’re not separate from that, and they have to make

moral decisions based on that. So maybe that won’t shoot me dead, but

they might tear gas the hell out of me to make me stop what I’m doing if

it’s against their interests.

Diebenow: And that played out yesterday in Oakland. Even with the supposed “non-violent” weapon like rubber bullets.

crow: It’s

less lethal. I mean, I know you’re using quotation marks, but let’s be

clear about it. Rubber bullets are less lethal. They’re not non-lethal. I

know people who have been incredibly injured by them.

Diebenow: So

in the way it’s playing out right now nationwide, it’s kind of as you’d

expect it in terms of the reaction of the state with the Occupy

movement.

crow: Let’s really talk about what’s

important about the Occupy movement. You’re talking about a movement

that hasn’t happened in the United States in a long time—a decentalized

movement not controlled by any central organization or anything, where

people rose up because things were wrong all over. The tea party, which

was similar thing on the right-leaning spectrum, was always geared

toward funnelling people into the Republican Party, or it was quickly

co-opted by people that had interest in doing it, like Dick Armey who

used to be at the University of North Texas here.

But the Occupy

movements are totally decentralized. It’s 30 years of anarchist and

horizontal organizing coming to fruition, where you talk about General

Assembly, where you talk about concensus decisions, where you try to

hear the voices of the people who aren’t normally heard.

Are

there problems within that? Yeah, but that’s an amazing start for

something. All the Occupy movements—nobody is going around saying, “Hey,

you should start an occupy movement. You should start an occupy

movement.” People are doing it because they have the sense of need to do

that. That is what we should be talking about. Not the state

repression.

Fuck the state. If we stay clear on what we are doing, it doesn’t matter what the state does.

Do

you know what I mean? Our will—our political will is much stronger than

anything they can throw at us. They don’t call it struggle for nothing,

right? But we stay focused on what we’re doing, and it doesn’t matter

what they do.

Diebenow: I liked your point about the terms long-term revolution and little revolution. It’s almost like little struggles.

crow: They are.

Diebenow:

So this is a big revolution in the sense that it was long time coming,

but it is still in a sense little revolutions for individuals.

crow: It

is totally baby steps. Every movement that rises up, like the

alternative globalization movement that I was talking about that was a

decade ago, it’s the same thing. But what happens is that we have no

institutional memory because we don’t carry it from movement to

movement. So the hundreds of thousands of people that were in the

alternative globalization movement left, and there’s only a few of us

left, and we’re the ones who tell the stories so that the new people who

are rising up can (learn), and in 10 years, these people can tell the

stories.

Diebenow: I was listening to Amy

Goodman talk the other night, and she was saying how she studies

movements. And what was interesting was when you said you studied

revolutions. Is there a difference?

crow: Revolutions

are the idea that we have to overturn all of these things to make

things happen. Movements are what rises up when we try to make these

revolutionary situations, and the things that come out of them. I’m not

talking old school like we’re going to rise up one day, fight and then

we take state power. That’s not the kind of revolutions I’m talking

about. Actually, I don’t even know what they can look like. They’re

going to move faster in some areas and slower in other areas, but the

little mini-revolutions are happening daily. First it’s the wakening of

each and every one of us, and then us pulling together and doing things,

and then inheriting the other movements that came before us, and then

building on those futures, which we don’t even know what they’re going

to be yet. And I’m okay with that. I used to not because I wanted a

plotted out plan: “We’re going to do this, this and this. And then next

thing there is, we’re all free.” But that’s not going to happen.

But

what’s different with the Occupy movement is that nobody wants to

control anything. The tea party wanted to control things. I don’t want

to hit them with a broad stroke because I think that’s unfair, too,

because there’s a lot of legitimate people within the tea party

movement, and there was a huge spectrum of interest within that, right?

But ultimately when they got funnelled in, they wanted to control what

happened in the new store. We don’t want to control that. We want to

create new worlds from below and from the left that we don’t even know

what they are. We’re imagining something different, and people are

waking up and trying to reimagine what those worlds are. We’ve all been

in these cages that we can’t see, and people are waking up, starting to

go, “Wow. I’m not in that cage, but what is it like to be free? I knew

what I could do inside the cage, but now I have to figure out . . . ”

And those paths are much harder. That’s where I come to that thing

“walking and asking.” So you continue to ask questions along the

way. And the thing is, these are the modern revolutions. The

Zapatistas set that up, where you didn’t have to have the answers

because we don’t have the answers, and that makes us have fallible but

human revolutions on a global scale.

Diebenow: One final thought: the Occupy movement has created an alternative government.

crow: If

you think about it, the Occupy movement in city after city, they are

practicing democracy— direct democracy—not where you’re voting your life

away for somebody 3,000 miles away from you who is going to tell you

what to do. You’re actually practicing it. And that takes a lot of time.

We’ve been resisting for so long, and we need to build. Our resistance

arm is totally muscular and really strong, but our building arm is

totally atrophied because we’ve ignored it. Now we’re beginning to

practice building it. It is like alternative governments and alternative

societies. We have to re-imagine it. It’s baby steps. Just because not

everybody is on board with some clear agenda is beautiful to me because

it shows the openness and the willingness to really think about it and

let it stew. In all the movements like in Argentina and what rose up in

Chiapas, Mexico, that’s what’s happened with people. The uprising in

Chiapas, Mexico, in 1994 was 20 years in the making. Twenty years they

talked about it before they decided to do that.

Diebenow: In a wider sense, is this like an Abraham Lincoln Brigade? Is that movement part of this movement’s history as well?

crow:

You’re talking the Spanish Civil War. That’s a totally different thing.

That was a clear enemy. They were fighting against fascism and for

anarchism and socialism. This is way different than that. I wouldn’t

compare it to that at all. I would compare it to Argentina in 2000, and

before that, I would compare it to Central American movements in the

1970s. It’s people’s uprisings. The thing is, there’s no leaders to

telling people they should up-rise. There’s no Communist Party. There’s

no Socialist Party. And everybody doesn’t want a socialist state.

That’s

not what I want. I’m not trying to build a socialist state. I want to

abolish the state. I want us to build grassroots power. I want to take

the longest, hardest path that we can find to figure out what it’s going

to be. I don’t want an easy answer because easy answers end up with

dictators and fascists.

-FIN-