by Josh Harkinson

Mother Jones

September/October 2011

To

many on the left, Brandon Darby was a hero. To federal agents consumed

with busting anarchist terror cells, he was the perfect snitch.

For

a few days in September 2008, as the Republican Party kicked off its

national convention in St. Paul, Minnesota, the Twin Cities were a

microcosm of a deeply divided nation. The atmosphere around town was

tense, with local and federal police facing off against activists who

had descended upon the city. Convinced that anarchists were plotting

violent acts, they sought to bust the protesters’ hangouts, sometimes

bursting into apartments and houses brandishing assault rifles. Inside

the cavernous Xcel Energy convention center, meanwhile, an

out-of-nowhere vice presidential nominee named Sarah Palin assured tens

of thousands of ecstatic Republicans that her running mate, John McCain,

was “a leader who’s not looking for a fight, but sure isn’t afraid of

one either.”

The same thing might have been said of David McKay

and Bradley Crowder, a pair of greenhorn activists from George W. Bush’s

Texas hometown who had driven up for the protests.

Wide-eyed

guys in their early 20s, they’d come of age hanging out in sleepy

downtown Midland, commiserating about the Iraq War and the

administration’s assault on civil liberties.St. Paul was their first

large-scale protest, and when they arrived they were taken aback: Rubber

bullets, flash-bang grenades, tumbling tear-gas canisters—to McKay and

Crowder, it seemed like an all-out war on democracy. They wanted to

fight back, even going so far as to mix up a batch of Molotov cocktails.

Just before dawn on the day of Palin’s big coming out, a SWAT team

working with federal agents raided their crash pad, seized the Molotovs,

and arrested McKay, alleging that he intended to torch a parking lot

full of police cars.Since only a few people knew about the firebombs,

fellow activists speculated that someone close to McKay and Crowder must

have tipped off the feds. Back in Texas, flyers soon began appearing at

coffeehouses urging leftists to beware of Brandon Darby, an “FBI

informant rat loose in Austin.”

The allegation came as a shocker;

Darby was a known and trusted member of the left-wing protest crowd.

“If Brandon was conning me, and many others, it would be the biggest lie

of my life since I found out the truth about Santa Claus,” wrote Scott

Crow, one of many activists who rushed to defend him at first. Two

months later, Darby came clean. “The simple truth,” he wrote on

Indymedia.org, “is that I have chosen to work with the Federal Bureau of

Investigation.”

Darby’s entanglement with the feds is part of a quiet resurgence of FBI interest in left-wingers.

From the Red Scare days of the 1950s into the ’70s, the FBI’s Counter

Intelligence Program, a.k.a. COINTELPRO, monitored and sabotaged

communist and civil rights organizations.

Nowadays, in what

critics have dubbed the Green Scare, the bureau is targeting the

global-justice movement and radical environmentalists. In 2005, John

Lewis, then the FBI official in charge of domestic terrorism, ranked

groups like the Earth Liberation Front ahead of jihadists as America’s

top domestic terror threat.

FBI stings involving informants have

been key to convicting 14 ELF members since 2006 for a string of

high-profile arsons, and to sentencing a man to 20 years in prison for

conspiring to destroy several targets, including cell phone towers.

During the St. Paul protests, at least two additional informants

infiltrated and helped indict a group of activists known as the RNC

Eight for conspiring to riot and damage property.

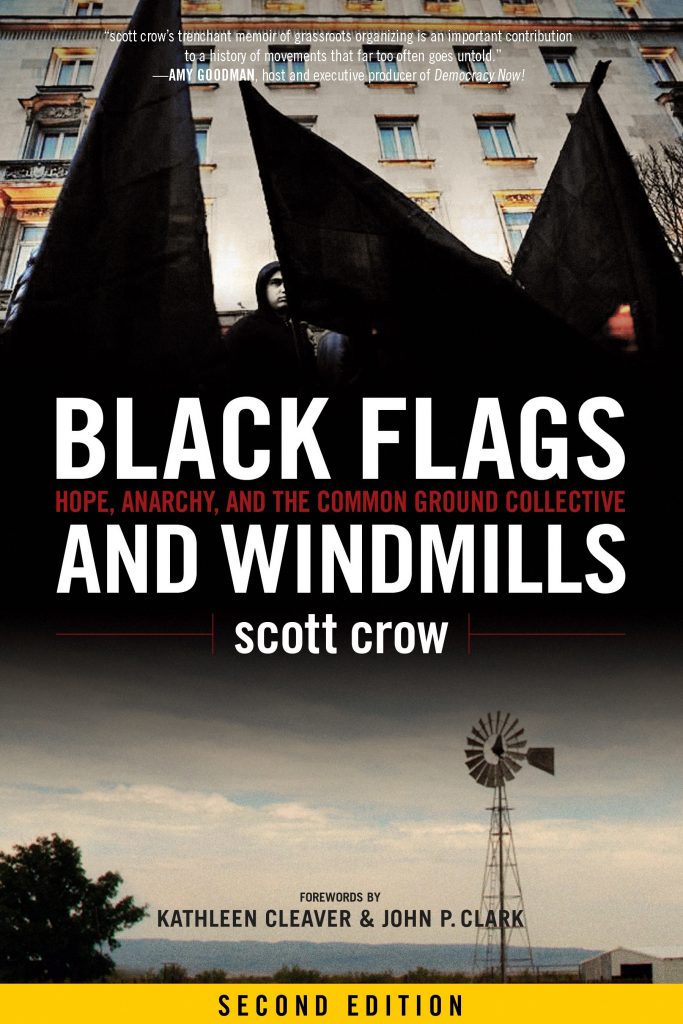

Brandon Darby.

Courtesy Loteria FilmsBut it’s Darby’s snitching that has provided the

most intriguing tale. It’s the focus of a radio magazine piece, two

documentary films, and a book in the making. By far the most damning

portrayal is Better This World, an award-winning doc that garnered rave

reviews on the festival circuit and is slated to air on PBS on September

6. The product of two years of work by San Francisco Bay Area

filmmakers Katie Galloway and Kelly Duane de la Vega, it dredges up a

wealth of FBI documents and court transcripts related to Darby’s

interactions with his fellow activists to suggest that Darby acted as an

agitator as much as an informant. (Watch the trailer and read our

interview with the filmmakers here.)

The film makes a compelling

case that Darby, with the FBI’s blessing, used his charisma and street

credibility to goad Crowder and McKay into pursuing the sort of actions

that would later land them in prison. Darby flatly denies it, and he

recently sued the New York Times over a story with similar implications.

(The Times corrected the disputed detail.) “I feel very morally

justified to do the things that I’ve done,” he told me. “I don’t know if

I could have handled it much differently.”

Darby “gets in

people’s minds and can pull you in,” one activist warned me. “He’s a

master. And you are going to feel all kinds of sympathy for him.”

Brandon

Michael Darby is a muscular, golden-skinned 34-year-old with Hollywood

looks and puppy-dog eyes. Once notorious for sleeping around the

activist scene, he now often sleeps with a gun by his bed in response to

death threats. His former associates call him unhinged, a megalomaniac,

a manipulator. “He gets in people’s minds and can pull you in,” Lisa

Fithian, a veteran labor, environmental, and anti-war organizer, warned

me before I set out to interview him. “He’s a master. And you are going

to feel all kinds of sympathy for him.”

The son of a refinery

welder, Darby grew up in Pasadena, a dingy Texas oil town. His parents

divorced when he was 12, and soon after he ran away to Houston, where he

lived in and out of group homes. By 2002, Darby had found his way to

Austin’s slacker scene, where one day he helped his friend,

medical-marijuana activist Tracey Hayes, scale Zilker Park’s 165-foot

moonlight tower (of Dazed and Confused fame) and unfurl a giant banner

painted with pot leaves that read “Medicine.” They later “hooked up,”

Hayes says, and eventually moved in together. She introduced him to her

activist friends, and he started reading Howard Zinn and histories of

the Black Panthers.

Some local activists wouldn’t work with Darby

(he liked to taunt the cops during protests, getting them all riled

up). But that changed after Hurricane Katrina, when he learned that

Robert King Wilkerson, one of the Angola Three—former Black Panthers who

endured decades of solitary confinement at Louisiana’s Angola

Prison—was trapped in New Orleans. Darby and Crow drove 10 hours from

Austin towing a jon boat. When they couldn’t get it into the city, Darby

somehow harangued some Coast Guard personnel into rescuing Wilkerson.

The story became part of the foundation myth for an in-your-face New

Orleans relief organization called the Common Ground Collective.

It

would eventually grow into a national group with a million-dollar

budget. But at first Common Ground was just a bunch of pissed-off

anarchists working out of the house of Malik Rahim, another former

Panther. Rahim asked Darby to set up an outpost in the devastated Ninth

Ward, where not even the Red Cross was allowed at first. Darby brought

in a group of volunteers who fed people and cleared debris from houses

while being harassed by police, right along with the locals who had

refused to evacuate. “If I’d had an appropriate weapon, I would have

attacked my government for what they were doing to people,” he declared

in a clip featured in Better This World. He said he’d since bought an

AK-47 and was willing to use it:

“There are residents here who

have said that you will not take my home from me over my dead body, and

we have made a commitment to be in solidarity with those residents.”

But

Common Ground’s approach soon began to grate on Darby. He bristled at

its consensus-based decision making, its interminable debates over

things like whether serving meat to locals was serving oppression. He

idolized rugged, iconoclastic populists like Che Guevara—so, in early

2006, he jumped at a chance to go to Venezuela to solicit money for

Katrina victims.

Darby was deeply impressed with what he saw,

until a state oil exec asked him to go to Colombia and meet with FARC,

the communist guerrilla group. “They said they wanted to help me start a

guerrilla movement in the swamps of Louisiana,” he told “This American

Life” reporter Michael May. “And I was like, ‘I don’t think so.'” It

turned out armed revolution wasn’t really his thing.David McKay.

Courtesy Loteria Films

Darby’s former friends dispute the

Venezuela story as they dispute much that he says. They accuse him of

grandstanding, being combative, and even spying on his rivals. In his

short-lived tenure as Common Ground’s interim director, Darby drove out

30 volunteer coordinators and replaced them with a small band of

loyalists. “He could only see what’s in it for him,” Crow told me. For

example, Darby preempted a planned police-harassment hot line by making

flyers asking victims to call his personal phone number.

The

flyers led to a meeting between Darby and Major John Bryson, the New

Orleans cop in charge of the Ninth Ward. In time, Bryson became a

supporter of Common Ground, and Darby believed that they shared a common

dream of rebuilding the city. But he was less and less sure about his

peers. “I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I’ve replicated every system that I fought

against,'” he recalls. “It was fucking bizarre.”

By mid-2007,

Darby had left the group and become preoccupied with the conflict in

Lebanon. Before long, Darby says, he was approached in Austin by a

Lebanese-born schoolteacher, Riad Hamad, for help with a vague plan to

launder money into the Palestinian territories. Hamad also spoke about

smuggling bombs into Israel, he claims.

Darby says he discouraged

Hamad at first, and then tipped off Bryson, who put him in touch with

the FBI. “I talked,” he told me. “And it was the fucking weirdest

thing.” He knew his friends would hate him for what he’d done. (The FBI

raided Hamad’s home, and discovered nothing incriminating; he was found

dead in Austin’s Lady Bird Lake two months later—an apparent suicide.)

McKay

and Crowder first encountered Darby in March 2008 at Austin’s Monkey

Wrench Books during a recruitment drive for the St. Paul protests.

Later, in a scene re-created in Better This World, they met at a café to

talk strategy. “I stated that I wasn’t interested in being a part of a

group if we were going to sit and talk too much,” Darby emailed his FBI

handlers. “I stated that I was gonna shut that fucker down.”

“My

biggest impression from that meeting was that Brandon really dominated

it,” fellow activist James Clark told the filmmakers. Darby’s FBI email

continued: “I stated that they all looked like they ate too much tofu

and that they should eat beef so that they could put on muscle mass. I

stated that they weren’t going to be able to fight anybody until they

did so.” At one point Darby took everyone out to a parking lot and threw

Clark to the ground. Clark interpreted it as Darby sending the message:

“Look at me, I’m badass. You can be just like me.” (Darby insists that

this never happened.)

“The reality is, when we woke up the next day, neither one of us wanted to use” the Molotovs, Crowder told me.

When

the Austin activists arrived in St. Paul, police, acting on a Darby

tip, broke open the group’s trailer and confiscated the sawed-off

traffic barrels they’d planned to use as shields against riot police.

They soon learned of similar raids all over town. “It started to feel

like Darby hadn’t amped these things up, and it really was as crazy and

intense as he had told us it was going to be,” Crowder says. Feeling

that Darby’s tough talk should be “in some ways, a guide of behavior,”

they went to Walmart to buy Molotov supplies.

“The reality is,

when we woke up the next day, neither one of us wanted to use them,”

Crowder told me. They stored the firebombs in a basement and left for

the convention center, where Crowder was swept up in a mass arrest.

Darby and McKay later talked about possibly lobbing the Molotovs on a

police parking lot early the next morning, though by 2:30 a.m. McKay was

having serious doubts. “I’m just not feeling the vibe on the street,”

he texted Darby.

“You butt head,” Darby shot back. “Text me when

you can.” He texted his friend repeatedly over the next hour, until well

after McKay had turned in. At 5 a.m., police broke into McKay’s room

and found him in bed. He was scheduled to fly home to Austin two hours

later.

Bradley Crowder. Courtesy Loteria FilmsThe feds ultimately

convicted the pair for making the Molotov cocktails, but they didn’t

have enough evidence of intent to use them. Crowder, who pleaded guilty

rather than risk trial, and a heavier sentence, got two years. McKay,

who was offered seven years if he pleaded guilty, opted for a trial,

arguing on the stand that Darby told him to make the Molotovs, a claim

he recanted after learning that Crowder had given a conflicting account.

McKay is now serving out the last of his four years in federal prison.

At

South Austin’s Strange Brew coffeehouse, Darby shows up to meet me on a

chromed-out Yamaha with flames on the side. We sit out back, where he

can chain-smoke his American Spirits. Darby is through being a leftist

radical. Indeed, he’s now an enthusiastic small-government conservative.

He loves Sarah Palin. He opposes welfare and national health care. “The

majority of things could be handled by people and by communities,” he

explains. Climate change is “a bandwagon” and the EPA should be

“strongly limited.” Abortion shouldn’t be a federal issue.

He

sounds a bit like his new friend, Andrew Breitbart, who made his name

producing sting videos targeting NPR, ACORN, Planned Parenthood, and

others. About a year after McKay and Crowder went to jail, Breitbart

called Darby wanting to know why he wasn’t defending himself against the

left’s misrepresentations. “They don’t print what I say,” Darby said.

Breitbart offered him a regular forum on his website, BigGovernment.com.

Darby now socializes with Breitbart at his Los Angeles home and is

among his staunchest defenders. (Breitbart’s takedown of ACORN, he says,

was “completely fucking fair.”)

“No matter what I say, most

people on the left are going to believe what reinforces their own

narrative,” Darby says. “And I’ve quit giving a shit.”

Entrapment?

Darby scoffs at the suggestion. He pulls up his shirt, showing me his

chest hair and tattoos, as though his macho physique had somehow seduced

Crowder and McKay into mixing their firebombs. “No matter what I say,

most people on the left are going to believe what reinforces their own

narrative,” he says. “And I’ve quit giving a shit.”

The fact is,

Darby says, McKay and Crowder considered him a has-been. His tofu

comment, he adds, was a jocular response after one of them had ribbed

him for being fat. “I constantly felt the need to show that I was still

worthy of being in their presence,” he tells me. “They are complete

fucking liars.” As for those late-night texts to McKay, Darby insists he

was just trying to dissuade him from using the Molotovs.

He

still meets with FBI agents, he says, to eat barbecue and discuss his

ideas for new investigations. But then, it’s hard to know how much of

what Darby says is true. For one, the FBI file of his former friend

Scott Crow, which Crow obtained under a Freedom of Information Act

request last year, suggests that Darby was talking with the FBI more

than a year before he claims Bryson first put him in touch. Meanwhile,

Crow and another activist, Karly Dixon, separately told me that Darby

asked them, in the fall of 2006, to help him burn down an Austin

bookstore affiliated with right-wing radio host Alex Jones. (Hayes,

Darby’s ex, says he told her of the idea too.) “The guy was trying to

put me in prison,” Crow says.

Such allegations, Darby claims, are

simply part of a conspiracy to besmirch him and the FBI: “They get

together, and they just figure out ways to attack.” Believe whomever you

want to believe, he says. “Either way, they walk away with scars—and so

do I.”