By Christian Hogsbjerg

Race & Class

March 2019

The

republication, thirty years after it was first written in 1988, of Paul

Buhle’s pioneering biography of the Trinidadian writer and

revolutionary C. L. R. James, ‘the artist as revolutionary’, might at

first sight be viewed slightly cynically as an attempt by Verso to join –

or perhaps rather rejoin – what Robin D. G. Kelley in his new foreword

to the work somewhat provocatively calls ‘a literary gold rush’ around

James. Yet this would be a mistaken judgement, for as the ‘authorised

biography’ of James, Buhle’s work remains, and will always remain, both

distinc- tive by its very nature, despite the accumulation of new

knowledge about James and his life and work that has since come to

light, and educational and revelatory in its own right, thanks to

Buhle’s closeness to, and deep understanding of, his subject.

Though

the original work was written at some speed, Buhle’s The Artist as

Revolutionary successfully provided an account of James’s individual

political and intellectual evolution situated within a narrative about

the intertwined col- lective fate of the broader wider Left over the

course of the twentieth century, replete with thought-provoking

contrasts with other critical contemporary activ- ists and

intellectuals. With an eye for the telling quote, and making excellent

use of interviews he had conducted with James about his life, Buhle

brought to this work his own lived experience of socialist activism in

the American New Left, his understanding of Marxist theory as an early

youthful admirer of Daniel de Leon’s Socialist Labour Party, and his

skills as a social historian. To adequately contex- tualise James’s long

life, from his growing up in Port-of-Spain in colonial Trinidad in the

early twentieth century, to his turn to militant Pan-Africanism and

revolu- tionary socialism in 1930s Britain, to subsequent sojourns in

the United States, Caribbean and Africa amid decolonisation, is no small

task for any scholar writ- ing even now. But to do so when ‘James

scholarship’ was in its infancy was a remarkable achievement. Buhle’s

work also successfully succinctly and cogently summarised the wide

variety of James’s writings, from novels like Minty Alley to classic

socialist histories like World Revolution and The Black Jacobins to

treatises on Marxist philosophy such as Notes on Dialectics and works of

literary criticism such as Mariners, Renegades and Castaways (on

Melville’s Moby Dick).

Indeed, there are still hidden depths

to Buhle’s work – the original text of which he resisted the temptation

to change or update for this new edition – and even the most seasoned

scholar of black radicalism will benefit from reading, or perhaps more

likely, rereading, Buhle’s biography.

This is partly because

the period in which it was written ensured that it was written as a

‘political biogra- phy’ first and foremost. As Kelley rightly points out

in the foreword, the 1980s was a world ‘marked by crisis and its

antithesis: opportunity’, and ‘Buhle was part of a New Left generation

of writers, organisers, and scholars seeking a new direction for

revolutionary movements’ as official ‘Communism’ stagnated, declined and

then finally collapsed. Though Buhle’s biography made it clear enough

that his sympathies for a return to ‘Leninism’ in whatever form were

distinctly limited, and indeed he was open to the possibilities and

potentialities of postmodernist theory for new scholarship on James, he

closed his biography in 1988 still calling for ‘a Jamesian politics’.

Buhle quoted ‘the young old revolution- ary’ James himself, grappling

with the challenges of the 1980s but still stressing that the ‘workers

and peasants must realize that their emancipation lies in their own

hands and in the hands of nobody else’.

The new edition

includes a substantial, valuable and illuminating afterword, co-written

by Buhle and his collaborator Lawrence Ware, a lecturer in philoso- phy

at Oklahoma State University, entitled, ‘Reviewing – and Renewing – the

C.L.R. Legacy for the Twenty-First Century’. This among other things

reflects in a generous fashion on the new scholarship on James which has

appeared over the last thirty years, and provides a more detailed

commentary on aspects of James’s life and work which received less

attention and were less well known when the original biography was

written. The afterword to the new edition also includes a brief piece on

‘C.L.R. James Today’ by Ware, which attempts to situ- ate James in the

context of contemporary black struggles in the United States. This short

piece might be usefully read alongside a new ‘Palgrave Pivot’ publi-

cation by Ornette D. Clennon, a sociologist at Manchester Metropolitan

University, which tries to do the same for contemporary black struggles

in the United Kingdom: The Polemics of C.L.R. James and Contemporary

Black Activism. It is obviously encouraging that a new generation of

black ‘critical race theorists’ in both the US and UK are turning to

James and engaging with his life, work and legacy for thinking about

questions of race and resistance amid the current BlackLivesMatter

Movement.

Clennon, in particular, is to be congratulated for

making the critical intellec- tual effort to try and wrestle

theoretically with how James might have made sense of the contemporary

critical moment in Britain, amid ‘Brexit’ and the rise of Corbynism. He

writes about how he metaphorically ‘became friends’ with James and came

to appreciate his ‘intense intellectual creativity and playfulness’ as a

theorist after getting involved with a short-lived and sadly defeated

com- munity campaign in 2015 to try to revive the derelict ‘Nello James

Centre’ in Whalley Range, South Manchester, as a resource centre for the

local black com- munity, as, for decades, it had once been after its

founding in 1967. As might be expected from someone who freely admits

that he has only begun really reading and thinking about James over the

last couple of years, Clennon’s work – despite its somewhat grandiose

title – is less about ‘the polemics of C.L.R. James’ than it is about

using a rather random and limited selection of James’s essays (mainly

about black struggles in Jim Crow America from the 1940s and 1950s) as

an entry point for Clennon to give us his own take on ‘contemporary

black activism’ in Britain from the perspective of what he calls ‘a

synthesis of Post-Colonial and Post-Marxist theories’.

As a

result, perhaps we ultimately learn more about Clennon and his politics

than we do about James and his. Clennon’s take on ‘Brexit’ is that a new

English ‘colonial administration’ has emerged which, under a

bureaucratic deception of ‘social unity’, ‘encouraged synthetic

anti-immigrant sentiment of the masses during the Referendum’; there is

also a sense of the contemporary and historic tensions between black

community organisations and trade unions in Britain around various black

struggles. Though Clennon praises James’s polemics for representing ‘an

unguarded and visceral James that enables him to display his

outstanding abilities in the areas of cultural commentary, historical

and critical thinking’, James’s Marxism is deemed flawed both for its

advocacy of multira- cial working-class unity and the fact it is

apparently unable to come to terms with the challenges posed by the rise

of neoliberalism. For Clennon, ‘not only has capitalism transcended the

notion of the nation state, it has permeated the culture of our

institutions, our ways of thinking, and in so doing, it has drasti-

cally re-orientated our psychic spaces’. Indeed, ‘neoliberalism has

become too entrenched a Zeitgeist for us to un-imagine’, though how

Clennon manages to utilise his imagination effectively in order to

analyse it, when apparently the masses are unable to make this leap,

remains unclear.

Indeed, such an argument about neoliberalism, in

the British context at least, appears to be belied by the rise of

Corbynism, and Clennon accepts that ‘with Momentum leading a grass-

roots surge in support of Corbyn … there does appear to be an appetite

from certain quarters to put an end to our system of “colonial

administration”’.

However, ‘the utter end of capitalism and the introduction of a post-racial social- ism’ apparently remains ‘a utopian ideal’, and so the best we can learn from James is how ‘to be creative in our resistance’ to neoliberalism, working ‘from within the system’. Whatever the strengths of Clennon’s work, it hardly makes for a particularly insightful read if the reader was hoping for a book that would seri- ously try to apply a radical ‘Jamesian’ perspective to contemporary black strug- gles in the UK. Such a book would surely have as its bedrock the considerable rich body of writing and speeches by James on black struggles in Britain from the 1930s up to the 1980s – though admittedly much of these remain scattered and hidden away in often hard to find publications.

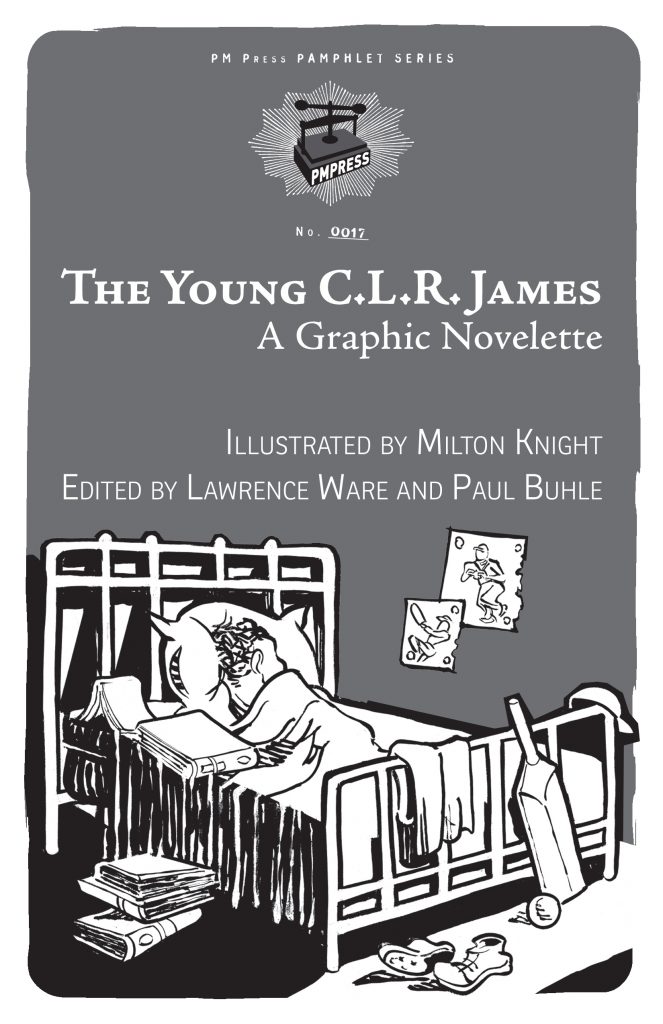

With respect to future

directions in James scholarship, Buhle and Ware rightly note that in

particular ‘more research needs to be done in Trinidad’ with respect to

understanding his early life. The two have worked with black American

car- toonist Milton Knight to produce The Young C.L.R. James: a graphic novelette,

which brings some of the autobiographical elements of James’s Beyond a

Boundary to life in Knight’s distinctive style, and in a format – a

‘graphic novelette’ – that has the potential to enable the story of

James’s early life to reach new, younger audiences. This was originally

envisioned as a project which would ambitiously try to cover the whole

of James’s life, and sadly we just have here ‘chapter one’ on ‘the

little black puritan’ in colonial Trinidad, together with some sketches

about the 1936 London production of James’s play Toussaint Louverture.

Though Knight’s idiosyncratic ‘Americanised’ style is something of an

acquired taste, and one can imagine many cricket purists in particular

raising the odd eyebrow over depictions of cricket matches which

resemble baseball games, nonetheless one is left wanting more. Given the

success of Kate Evans’s superb Red Rosa, about the life of Rosa

Luxemburg, it is to be hoped that Knight might one day be inspired

enough to return to his portrayal of James’s revolutionary life, and

give us ‘Red C.L.R.’.

Back to Milton Knight’s Artist Page| Back to Paul Buhle’s Editor Page | Back to Lawrence Ware Editor’s Page