By Leslie Thatcher

Truthout

October 28th, 2012

Retired

Madison University Professor, Truthout contributing author and producer

of nonfiction comics Paul Buhle talked to Truthout by email recently

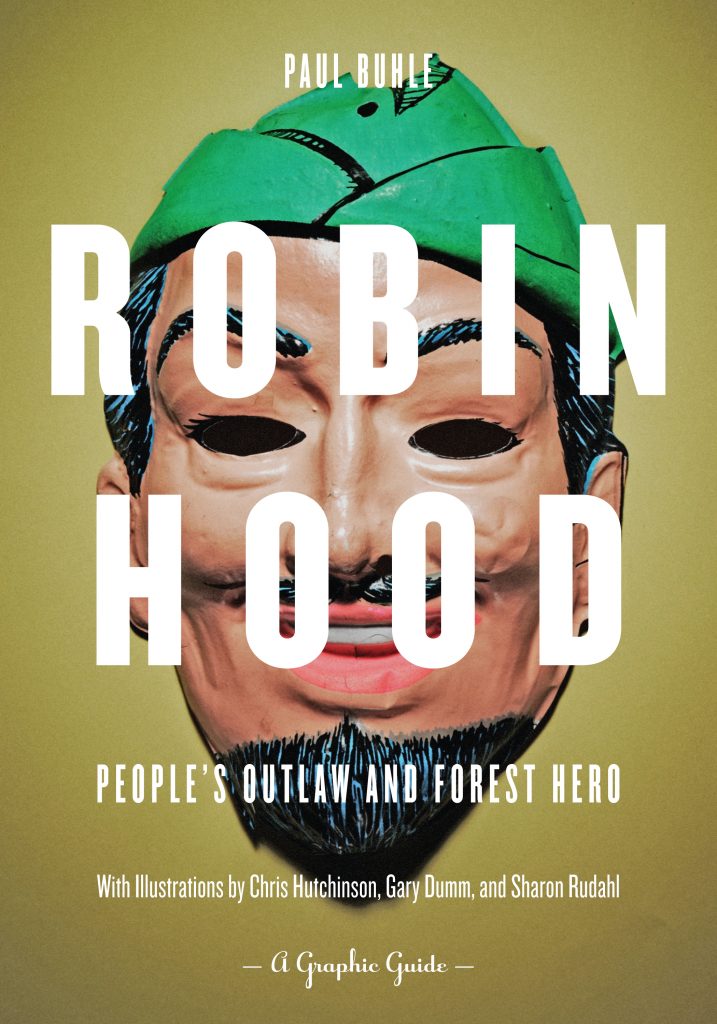

concerning his 2011 book, “Robin Hood: People’s Outlaw and Forest Hero,” illustrated by Chris Hitchinson, Gary Dumm and Sharon Rudahl, published by PM Press, Oakland, CA. 107 pages

Leslie Thatcher for Truthout: Paul, can you tell our readers why Robin Hood, why now?

Paul Buhle: As I try to argue in the book, but too briefly, the “enclosure” of the world, mirroring the enclosures six or seven hundred years ago in the English countryside (Karl Marx, among others, wrote brilliantly on this subject), spread human misery and vast environmental change, as they spread the market society outward. It is not an untouched “nature” that is overwhelmed in the process, but open spaces together with spaces cultivated by small-scale rural economies for centuries, at risk of eradication.

Robin Hood, the mythic figure, appears in the generational aftermath of a Europe’s first (if failed) mass uprising, the Wat Tyler Rebellion of 1381. Mythic Robin protects an old village society and its rules against the new oppression of the Normans, who did indeed make familiar practices (such as the killing of deer for food) into capital crimes, and pressing villages for higher taxes—en route to the enclosures to come.

Today there are all sorts of nonprofits, international human rights groups, etc., but the enclosures and exclusions (terrorizing and driving rural folk away from vast corporate mining projects in Colombia, for instance) are barely slowed, let alone halted.

We need Robin Hood because he protects the “outside” and the “outsiders.” A precursive champion of Occupy, he occupies the Greenwood, has comrades in the centers of oppression (Maid Marian is the most effective) and the support of the common village folk. He is larger than life but also part of life. Within English language lore, there has been no one in almost a thousand years who is so popular, not even King Arthur or Sir Galahad. Robin defeats the criminalization of poverty by resisting the criminality of the upper classes.

We

need Robin also because from an early time, perhaps the 15th century,

the Robin Hood saga was re-enacted annually in English villages as a

Mayday drama, recalling the pre-Christian celebration of Spring and of

fertility for humans, animals and plants alike. Robin Hood and Maid

Marian are spiritual beings, Liberation Theology prototypes but not

celibate! Marian, the proto feminist, is his equal and his lover.

We

both share a passion for the Robin Hoods series starring Richard

Greene, produced in the 1950s, for which your book provides some of the

backstory. Please tell our readers how that series embodied some of the

themes of the legend in its very production.

Paul Buhle This is an especially fascinating story (I was able to describe a little of it in the New York WNYC/NPR show Fishko Files, excerpts run in the NPR national “On the Media,” a few years ago) to me personally, because my parents bought a television almost as Robin Hood came on the air. The series shaped my ideas as a teenager, preparing me for discovering the local Civil Rights movement a few years later and the antiwar movement some years after that. My collaborator, veteran investigative reporter Dave Wagner, and I wrote at length about the Robin Hood series in our book, Hide in Plain Sight: The Hollywood Blacklistees in Film and Television, 1950-2002.

One of the two principal scriptwriters for the series, Oscar-winning (but blacklisted) Ring Lardner, Jr., had become a good friend, as had its first script editor, Al Ruben, and especially an occasional writer of the series, Robert Lees, a veteran of slapstick Abbott and Costello comedies. So you could say that I had come full circle, discovering the secret behind the greatness of the series. Other adaptations of the Robin Hood saga are fine, as I discuss in Robin Hood: People’s Outlaw and Forest Defender, especially Robin and Marian, the story of two former lovers reunited in old age. But none is so funny as the 1950s series, and none has a stronger female lead, or co-star.

Your book is cover-described as a “Graphic Guide.” What motivated you to choose this format and how did your graphic collaborators fix on their own contributions?

Paul Buhle I realized recently that a decade has gone by since I began preparing for WOBBLIES! A graphic history of the Industrial Workers of the World (published 2005). I’d been studying and writing radical history since the 1960s, founding a New Left journal, Radical America, creating an oral history archive of leftwing oldtimers, and among other work, coediting the Encyclopedia of the American Left. But I came back to comics because the art form had meant so much to me as a child, and so as to reach today’s young people. Robin Hood has its own history in comics, including a Classics Illustrated version that I must have read as a child. But comic art has grown up since then. Chris Hutchinson is properly a collage artist, and he uses his skills for a satirical saga, mostly about the oppressors; Sharon Rudahl has been an important feminist comic artist since the 1970s, so she captured the Maid Marian story; and Gary Dumm has been working with me on the Middle Ages, uprisings, religious revolts, and so on, and he did a fantastic job of tying Wat Tyler’s Revolt to the first important, radical English poem, “Piers Plowman.”

If you failed to mention imperialism, ethnic hatred, feminism, environmentalism, the criminalization of poverty, liberation theology or cheerful resistance to an immoral order in your answers above, please briefly describe how the Robin Hood legends relate to these specific modern concerns.

Paul Buhle I rewrite your question as: Why is Robin so HAPPY?

Robin is the happy revolutionary, happy to BE a revolutionary, and his Merry Men share his joy of life, love of quaffing ale, inviting villagers to woodland parties, and keeping everybody in the proper mood to resist oppression by resisting depression.

OK, you got me! You close the book and I’ll close the interview with the pertinent quote from Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer: The boys dressed themselves, hid their accoutrements, and went off grieving that there were no outlaws any more, and wondering what modern civilization could claim to have done to compensate for their loss. They said they would rather be outlaws a year in Sherwood Forest than President of the United States forever.