By Michael Schreiber

Socialist Action

July 12, 2012

As I write, in late May 2012, a playhouse here in Philadelphia is advertising its production of “Robin Hood” as an action play “aimed at kids five years and up.” At the same time, in Chicago, anti-NATO demonstrators are calling for a “Robin Hood tax” on financial transactions, as part of their demand to “tax the rich.”

Who is the real Robin?

Is he the swashbuckling hero portrayed in cartoons, TV, and Hollywood musicals? The class-conscious guerrilla leader, fighting to avenge the peasantry against their oppressors? Or perhaps the “Green Robin,” who with his Merry Men inhabits the woodlands in respectful harmony with Nature?

Robin is not the same champion to all people. Throughout

the centuries, he seems to have been redefined, if not re-invented, with

each telling of the tale. Nonetheless, scores of works have probed into

the question of Robin’s identity—an extraordinary quest, considering

that most investigators agree that the Robin Hood stories are mainly

fiction.

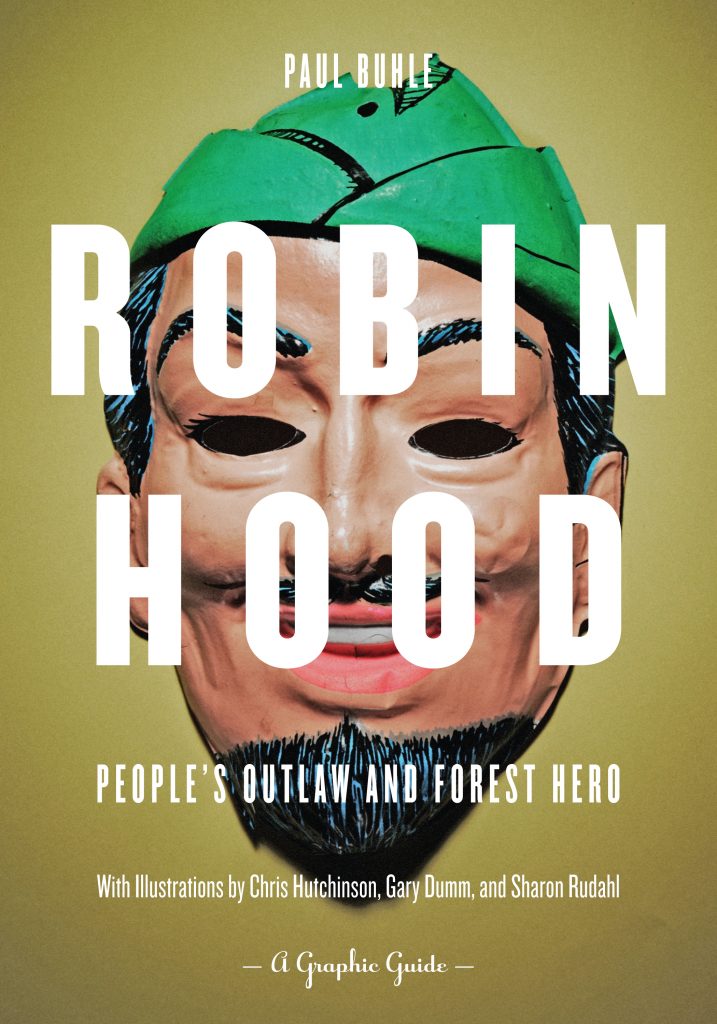

With his new book, Robin Hood: People’s Outlaw and Forest Hero, Paul Buhle, editor of the left journal Radical America,

enters the ranks of historians seeking to uncover the multiple themes

and meanings of the Sherwood Forest legend. In his conclusions, however,

Buhl readily sides with those who perceive that Robin over the

centuries has appeared primarily as a standard-bearer in battles against

injustice.

He states, “No other medieval European saga

has had the staying power of Robin Hood; no other is wrapped up

simultaneously in class conflict (or something very much like class

conflict), the rights of citizenship in their early definitions, defense

of the ecological systems, and the imagined utopia of freedom

disappearing into a mythical past.”

Buhle acknowledges, of course, that scriptwriters often eviscerate the political content of the Robin Hood legend. A number of recent movie renditions reduce the hero to little more than a romantic or heroic action figure. Or worse, they present him as the willing agent of jingoistic big-power politics. For example, says Buhle, while Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood mega-feature of a couple of years ago might give a slight nod to Robin’s role as the defender of downtrodden villagers, the subject “in practice only manages to protect one empire against another.”

The earliest known

references to Robin Hood in popular culture appeared in the early 13th

century, including in the rolls of several English justices. This

suggests that the outlines of the fictional character might be based,

however loosely, on the historical memory of the exploits of a real

person or persons.

Buhle skips over this tantalizing question, however, and begins his chronology many centuries later with The Dream of John Ball,

a novella by William Morris, artist and “father of British socialism.”

In this work, which was serialized for newspaper readers in 1886-87,

Morris plots the adventures of a man who leaps from the modern era into a

fourteenth-century English village. There he finds a group of yeomen

(independent small landowners) who have risen up against the corrupt

local sheriff and other Crown officers who seek to oppress them.

The

villagers are led by the lay preacher John Ball, a real though obscure

figure in English history. According to Morris, Ball led his followers

along the trail of rebellion blazed by Robin and his men. Thus, a ballad

singer in Morris’ narrative states to the time-traveler, “Was it not

sooth that I said, brother, that Robin Hood should bring us John Ball?”

John

Ball was a participant in the uprising of 1381, whose major leader was

Wat Tyler. The yeomen under Tyler’s command armed themselves with staves

and pitchforks and marched on London to protest high taxes and growing

poverty. After meeting with the King, Tyler was betrayed; he and Ball

were assassinated, and the movement was dispersed.

Buhle

argues that Wat Tyler’s uprising of 1381, “the first major outbreak of a

class and social conflict across England . . . prepared the ground for

the popularity of the Robin Hood saga.” Robin Hood was called into

existence by popular desires for a hero figure to represent their

struggles for social justice.

Perhaps the first allusion

to Robin in literature, William Langland’s “Piers Plowman,” appeared in

manuscript in the years immediately proceeding Wat Tyler’s rebellion.

In the story, Sloth, a priest, confesses, “I kan [know] not parfitly my

Paternoster as the preest it singeth, / But I kan rymes of Robyn Hood

and Randolf Erl of Chestre.” In other words, he cannot always remember

his prayers, but he can readily recite the ballads of popular heroes.

(Five centuries later, Mark Twain put a similar statement into the mouth

of the whimsical young rebel, Tom Sawyer.)

While Buhle convincingly argues that the period of Wat Tyler’s rebellion was a “Robin Hood era,” the reader might wonder why Buhle concentrates the better part of two chapters on those years alone. It was a full century after Wat Tyler that the efforts by landlords to enclose the pastures began to get fully underway in England, expelling thousands of small farmers from the countryside. Didn’t the impoverished population need Robin Hood at that moment to help chart a path of resistance?

Indeed,

Buhle briefly notes, Robin as protector of the poor appeared again in

the late fifteenth century in a collection of verse tales under the

title, “A Lyttell Geste of Robyn Hode.” But from the late sixteenth

century onward, a more conservative Robin began to enter English

literature, often as an official project to erase the militantly radical

one. Following the defeat of the Spanish armada, audiences saw Robin

Hood as a patriotic national hero on the London stage.

And Shakespeare’s Robin Hood-type characters, such as Orlando and the Duke in As You Like It, were noblemen who had temporarily fled palace life for a sylvan arcadia.

From

there, Buhle follows the contrasting renditions of Robin Hood and his

band through the centuries. Important examples include Joseph Ritson’s

popular volume of 1795, poet John Keat’s antiwar Robin and Marian of

1817, Walter Scott’s patriotic “Ivanhoe” of 1819, storyteller and

illustrator Howard Pyle’s “Merry Adventures” of 1883, and Errol Flynn’s

version filmed on the eve of World War II (1938), in which he vanquishes

(Hitlerite?) evil while vying for the heart of Olivia de Havilland’s

Maid Marian.

Buhle presents his chapters as a series of

almost autonomous essays. Each chapter is packed with facts and critical

insight, but often on themes that to a certain extent had been dealt

with earlier. The discontinuity and repetition in the narrative left me a

bit confused, at least on my first time thorough the book, over where

the author was leading his readers.

Luckily, the book’s

illustrations provide a framework to help us make sense of Buhle’s

choppy structure. The illustrations appear in four separate sections

that underscore major themes of the adjacent chapters. Gary Dumm gives

us a comic-strip portrayal of the peasant and religious struggles in

England of the fourteenth century. Christopher Hutchinson, a supporter

and contributor to Socialist Action newspaper, uses collage to

provide Robin Hood heroes for the modern age (Che, Malcolm, Harriet

Tubman, Rosa Luxemburg, etc.). And Sharon Rudahl’s cartoons tell the

tales of Maid Marian—warrior, revolutionary activist, and

proto-feminist.

Why read this book? Because the world

still has a need for Robin. Today, Buhle points out, “the rich and

powerful now command almost every corner of the planet and, in order to

maintain their control, threaten to despoil every natural resource to

the point of exhaustion. Meanwhile, billions of people are impoverished

below levels of decency during centuries of subsistence living.”

Yet resistance to authority continues, and so, Robin lives on “in the streets of Cairo, Egypt, and Madison, Wisconsin, USA, among the many other places where people dream of a better life and struggle for it openly, cheerful to be rebellious.”

The article above was written by Michael Schreiber, and is reprinted from the July 2012 print edition of Socialist Action newspaper.