by Paul Buhle

Truth out

April 25th, 2016

Why should we care about a failed independence uprising that occurred 100 years ago on April 24, led by Irish rebel James Connolly?

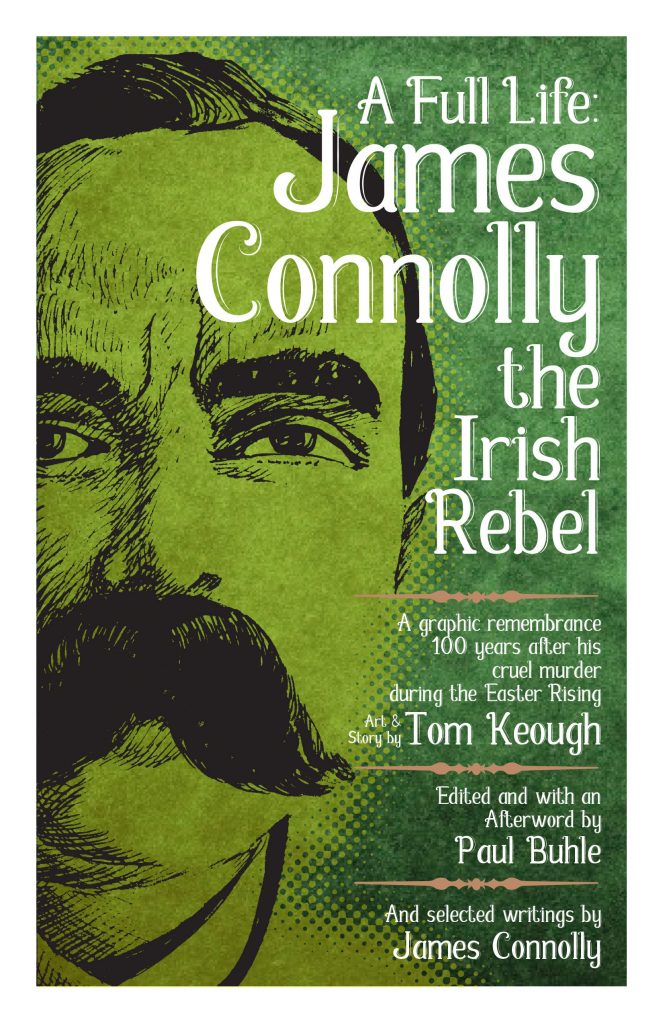

It’s a question answered within the pages of A Full Life: James Connolly the Irish Rebel, a graphic remembrance of Connolly illustrated by artist Tom Keough that I helped bring into the world.

It’s also a question that I might not have asked myself if I had not been in Dublin, Ireland, the day before Ireland’s marriage equality vote in May 2015.

The throng of young people in particular, eagerly distributing leaflets, cheering each other with smiles, waves and songs, was something to see. Same-sex marriage was clearly to be approved by a massive margin across the Republic. A literature table and some very grouchy characters represented the official, deeply anti-LGBTQ views of the Catholic Church in Ireland. The Catholic Church, with its views on divorce and much else, has long been utterly dominant in the Republic of Ireland, but has more recently been discredited by reports of child sexual abuse committed by priests and sex scandals involving clerics, and by the emergence of a new, more secular generation.

By May 2015, the solemn-faced devotees almost seemed harmless — remnants of an unpleasant and widely regretted past. When the vote came, the church politicians carried only one county. Ireland had come into modern times.Not quite times for a wide-ranging discussion of James-Connolly-style socialism, however. That remained for the future.

Something equally remarkable and unpredicted for 2015 happened in the United States. Here, Sen. Bernie Sanders began talking up one of Connolly’s great admirers, Eugene V. Debs. Before Sanders rekindled public interest in this topic, Debs — the most beloved socialist of US history — seemed to have vanished. A historic site devoted to Debs exists in Terre Haute, Indiana, and every now and then, the public hears once again about how Debs won nearly 1 million votes in the 1920 presidential election while campaigning from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary where he was being held as a political prisoner.

By way of contrast, the public in Ireland has never forgotten the story of James Connolly (1868-1916). Statues, portraits, inscriptions, assorted celebrations, songs from Connolly poems and songs about Connolly are recited or sung in Irish taverns by scores — all these seem available in any season. The run-up to the centenary of Connolly’s failed revolt for independence naturally offers a special case.

Connolly, actually born in Edinburgh, Scotland, among Irish immigrants seeking industrial labor, became a teenage factory worker and then British soldier until he managed a permanent AWOL, and then he became a socialist agitator and editor. Notorious in 1898 for leading a nationalist protest against a visit by Queen Victoria (among his fellow nationalists were poet William Butler Yeats and Maud Gonne, “the most beautiful woman in Europe”), Connolly continued to educate himself to an extraordinary degree. Meanwhile, he wrote immensely appealing, deeply sentimental class-conscious poetry. And then, broke as usual and with a growing family to feed, he abandoned Ireland for the United States.

On this side of the ocean, Connolly became an Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer, founded the Irish Socialist Federation and published its lively tabloid, The Harp, while writing furiously and traveling widely as a socialist lecturer. In 1910, Ireland called him home.

His extraordinary volume, Labour in Ireland — a historical inquiry into the workings of empire rivaling Marxist (or other) anti-imperialist analysis anywhere at the time — had as much as predicted catastrophic war between the rival empires. How right he was, and what conclusions to draw for Ireland’s quest to throw off the British yoke? “England’s adversity is Ireland’s opportunity,” according to the old adage. Against his own former reasoning that Irish capitalism would be no better than English bondage, he threw himself into plans for an uprising — the doomed uprising (or “Easter Rising”) of 1916.

Anticipations that the countryside would rise with the population of Dublin — or even that the poor population across Dublin itself would rise — proved worse than false. Within days, the Easter Rising was crushed. A badly wounded Connolly faced execution along with his comrades. But that would not be the end of the story, of course.

The British suppression was brutal almost beyond description. Wholesale murders, torture and the full gamut of horrors stirred Irish sentiment as the rebellion had not. In the end, the British seemed glad to get out, and in 1922, the Free State emerged. The former colonialists retained the northern six counties with mostly Protestant populations, planting the seed for future strife bordering upon internecine guerilla warfare, and for repressive state violence by British authorities.

The Irish Republic, nurturing nationalist resentments but run by a repressive clerical clique and a pack of corrupt politicians, remained a site of heroic memories alongside a most unheroic present. Connolly, the socialist ghost, inspired labor activists and a persistently fragmented left, recalled, if distantly, by the 2014 Ken Loach film Jimmy’s Hall. His mustache glowers out from photos and paintings, a sign of fierce resistance. But perhaps Connolly is best remembered as the autodidact theorist and inveterate sentimentalist who comes to life again in popular culture. Hence the James Connolly comic, A Full Life, with the artwork of a veteran Irish-American activist and of myself, an aging editor.