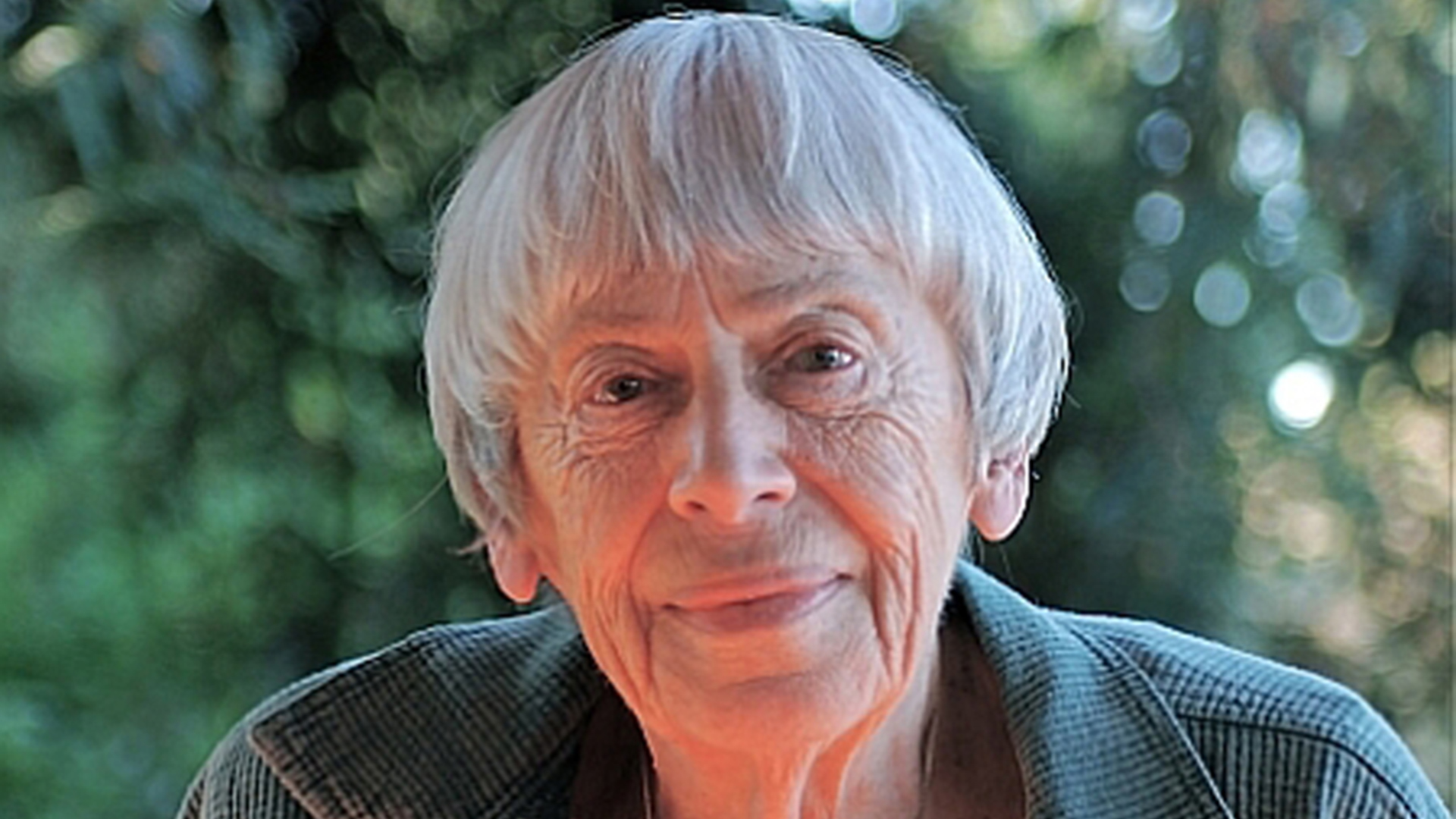

By Ursula K. Le Guin

Northwest Booksellers Association

May 18th, 2011

Just a couple of years ago I wrote that I thought the next big step in publishing would be print-on-demand. My prophecy failure rate continues to be perfect. We’re going direct to e-publication. And we’re going there very fast, in great disorder, riding an electronic avalanche.

I thought p.o.d. would dominate, because e-reading devices didn’t seem to be making much headway. Some people do use p.o.d., some are willing to read on their computers, some even practice palm-reading with Blackberries and such, but the leap over p.o.d must be largely due to the fact that usable e-readers are at last being widely produced. Now they need to be improved in quality and to come way down in price.

I don’t think print on paper will vanish any more than the pencil vanished when we started typing. The physical document is irreplaceably useful and durable. To think electronic storage can replace it is mere techno-hubris. But it looks as if, within a few years, most popular and ephemeral works, maybe most books of all kinds, will be published electronically and not on paper.

My personal reactions to this prospect:

As a reader, anything longer than a letter or a poem is tiresome for me to read on the screen. I read fast, carelessly, superficially on the screen, and don’t enjoy it. I don’t know why. I’ve composed on the computer for years now; I can edit on it fine; I can write on it for pleasure. Why can’t I read on it for pleasure?

For one thing, I like to read lying down.

Maybe

if I had a nice, light reader that didn’t have multiple functions for

every button, didn’t do a damn thing but show me clear text on two

facing full-sized pages, I’d soon be able to lie down with it and “sink

into” it as I do into print on paper. We are an adaptable species, and

habit changes everything.

But at this point, I’ll read what I can on paper, and make do with text on screen only if I have to.

As a professional writer making my living from my work, I’m a bit spooked. Once they saw faster profit in e-books than in print, big corporation-owned publishers started making grabs for e-rights, such as claiming that a book contract that didn’t explicitly mention rights for which the technology didn’t yet exist gave them, retrospectively, to the publisher. Now the contractual terms, advances, and royalties for e-books are all being worked out ad hoc and in a rush. At the moment, royalties, from the author point of view, look very good. But nobody seems entirely clear about how it will work. Publishers, agents, authors, we’re all riding the avalanche.

As for copyright, I am very worried. At this point the Web crawls with pirates offering copyrighted work for sale as e-publications, usually in badly degraded form; threatening them with copyright violation is just playing Whack-a-Mole, and nobody’s even trying to invoke the law on them. The Copyright Office has a huge job just keeping up with paper publication, and no clout in Congress. We saw Google’s success in shortcircuiting copyright (by getting some libraries to provide them copyrighted books to copy, by treating “orphaned” books as if they were books out of copyright, by claiming to release only “snippets,” a term even less definable than “fair use” is, and so on.) Judge Chin’s ruling against the Google Settlement does not, I fear, keep Google from leading the pirate fleet. Does copyright law end where the Web begins? Who will enforce it? Or what will replace it, enabling writers to live by their work?

As an author sharing responsibility for the state of my art, I fear control of availability (and of course content) by the corporations. Amazon’s offering only Amazon-owned books for their Kindle reader was an example. Books are not commodities, and readers are not consumers, but the corporations, cultureless, with no ethical guidelines, nothing but their own profit growth in view, will treat them as such so long as they are allowed to. A public kept in ignorance isn’t likely to even notice.

I welcome e-publication, so long as it works like an immense new-and-used bookstore network including bookstores selling both paper and e-books—and so long as it is fully and freely hooked up with the public libraries. The almost total failure of our schools to teach literature is causing a disastrous break in cultural continuity; many young people have read nothing written before 1990 or even 2000. E-publication offers vast availability and accessibility to older texts via our libraries.

Finally, as a very old author, I’m glad to see some of my longtime commercial publishers riding out the avalanche—battered, yes, but so far so good. And I rejoice in linking up when I can with smaller publishing houses on the West Coast, paper or electronic or both—about as far away from the corporations as you can get, these days. It’s like buying local produce. A bit gritty around the roots, maybe, but it tastes like it used to.

Le Guin credits her son, Theo Downes-Le Guin, for his ideas and suggestions for this essay. “Anyone my age needs a native informant from the computer generation,” she says. Le Guin’s latest book, The Wild Girls, is available in paperback from the small independent publisher PM Press. The book packages Nebula winner The Wild Girls, newly revised and presented in book form for the first time, with Le Guin’s scorching Harper’s essay, “Staying Awake While We Read.”

Le Guin needs no introduction here. She has published twenty-two novels, eleven volumes of short stories, three collections of essays, twelve books for children, six volumes of poetry and four of translation, and has received many awards: Hugo, Nebula, National Book Award, PEN-Malamud, the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Award (in 1986 for Always Coming Home and a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2001) and many others. Her recent publications include a volume of poetry, Incredible Good Fortune, the novel Lavinia, and an essay collection, Cheek by Jowl. She lives in Portland.