By John Plotz

10/15/2015

Public Books

What makes readers fall in love? You might want to start your answer by explaining Ursula Le Guin. I can only speak for one childhood—and one adulthood—spent reading Le Guin, but I’d bet my last nickel there are thousands of us out there. Tolkien knew how to conquer Evil; Beverly Cleary and Louise Fitzhugh put their finger on childhood woe and its embarrassments. But the nightly dreams of deep, deep blue water, of looking out from the crow’s nest of a battered clipper as it rounds a cliff, I owe to nobody but Le Guin. I can still close my eyes and count that ship’s sails. She owned me at age eight, on the overlit and understaffed second floor of the DC library (Chevy Chase branch). Four decades and God knows how many rereadings later, she owns me still.

If you think you have Le Guin pegged because you know young-adult fantasy, think again. Like other protean, inventive writers who move between speculative and realist fiction (Margaret Atwood, Doris Lessing, David Mitchell, Kazuo Ishiguro), Le Guin drops her reader into an uncanny double of our own world, a dream where somebody changed the names and shapes of everything and forgot to let you in on the secret. Le Guin’s peculiar gift, though, is to make the ordinary feel as important as the epic: mundane questions about who’s cutting firewood or doing the dishes share space with rune books and miscast spells. Her Earthsea has less in common with Narnia, Hogwarts, and Percy Jackson’s Camp Half-Blood than it does with medieval romances and Icelandic sagas, where dragons and death keep company with fishing yarns, goat-herding woes, and village quarrels.

Perhaps what most sets Le Guin apart from her peers is the vivacity of her worlds, the way she makes readers accept a world simultaneously distinct from and entirely a part of life as it’s ordinarily lived. I’m not talking so much about the vividness of a well-rendered video game as a curiously open-ended quality that makes you feel that her world is both very far away and right here in your own bedroom.

To be a Le Guin reader is to become accustomed to thinking on your feet, and to noticing that what you think has no guaranteed permanence:

Several black stones eighteen or twenty feet high stuck up like huge fingers out of the earth. Once the eye saw them it kept returning to them. They stood there full of meaning, and yet there was no saying what they meant. There were nine of them. One stood straight, the others leaned more or less, two had fallen. They were crusted with gray and orange lichen as if splotched with paint, all but one, which was naked and black, with a dull gloss to it. It was smooth to the touch, but on the others, under the crust of lichen, vague carvings could be seen, or felt with the fingers—shapes, signs. These nine stones were the Tombs of Atuan.1

Full of meaning, and yet there was no saying what they meant; that sums up just about everything you come across in a Le Guin story. You believe in her novels as a world apart, yet also find yourself struggling to relate that world to your own life. A double exposure. Jetlagged and homesick in a tiny, stuffy attic bedroom, I started reading A Wizard of Earthsea to my daughter once: “The island of Gont, a single mountain that lifts its peak a mile above the storm-racked Northeast Sea, is a land famous for wizards.” We were at home away.

In a pair of earlier articles,I praisedJean Stafford and Doris Lessing as writers who made careers out of rejecting proper places and suitably feminine roles: recalcitrants. Stafford hates the smothering effect of social norms; she spends her career inventing alternatives to cocktail parties and the (sexist and racist) rules of the game. But she can only imagine her antisocial alternative as austere, internal, unpopulated, and impossible. Lessing takes resistance a step further: she denies that social rules bind us the way we think they do, and she offers up a frequently impolitic vision of ways to stand apart from the flow of coercive empathy and misleading sympathy. If Stafford thinks to herself “I’m in Hell,” Lessing tells the rest of the world to go there.

Le Guin’s struggle is a subtler one. She’s against the notion that a unitary plot exists, one that knits every life together. Why should I be expected to join forces with my fellow Americans down the block? Her avowedly anarchist politics shape the way that her stories resist mobilization, and turn away from allowing anyone to stand in symbolically for the body politic.

Le Guin’s most influential booster, Fredric Jameson, praises in her work an impulse toward “world reduction.”2 He means that her writing presents a viable real-world politics because in it our crazily complex world is stripped, by fantasy, to its bare essentials. To Jameson, both the gender-bending The Left Hand of Darkness and the battle between anarchist Annares and capitalist Urras in The Dispossessed are simplifying allegories: they make our own world’s power elites visible, and hence resistible.

Jameson is responding to Le Guin’s desire to pare away the superfluous, honing each story to a knife-edge, so that nothing matters but a set of sharpened contact points. Consider the poem that opens the Earthsea series:

Only in silence the word,

only in dark the light,

only in dying life:

bright the hawk’s flight

on the empty sky.

Le Guin loves those moments when the difference between sea and land or sky and earth is narrowed to a line, a line the story simply traces, letting the solids that it divides fall away. However, by enlisting Le Guin in his critique of an overly complex capitalist world packed with superfluous choices, Jameson misses another equally crucial aspect of her vision. She is passionate about individual autonomy in the midst of a complex world: what we do, not in isolation, but among all the other business of the day.

What Le Guin reduces she immediately builds up again. She fines things down precisely in order to show readers how even the simplest world is fractured and multifarious. Consider not only the subtitle of The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia but also the complications that attend its opening image:

There was a wall. It did not look important. It was built of uncut rocks roughly mortared. An adult could look right over it, and even a child could climb it. Where it crossed the roadway, instead of having a gate it degenerated into mere geometry, a line, an idea of boundary. But the idea was real … The wall shut in not only the landing field but also the ships that came down out of space, and the men that came on the ships, and the worlds they came from, and the rest of the universe. It enclosed the universe, leaving Anarres outside, free.

Le Guin undoubtedly wants readers rooting for Anarres and its barren freedom. But the idea of creating your freedom by shutting out the big bad universe is a slippery one, and Le Guin wants to be sure we miss none of that slipperiness: Can’t you imagine an East German saying something like this about the Berlin Wall in 1974? Walls don’t close off possibilities in Le Guin. In fact, walls (a crucial one divides and in a sense joins the living and the dead in the Earthsea books) are what let possibilities multiply, giving readers the chance to stand on either side, or even to perch uncomfortably on top, looking both right and left.

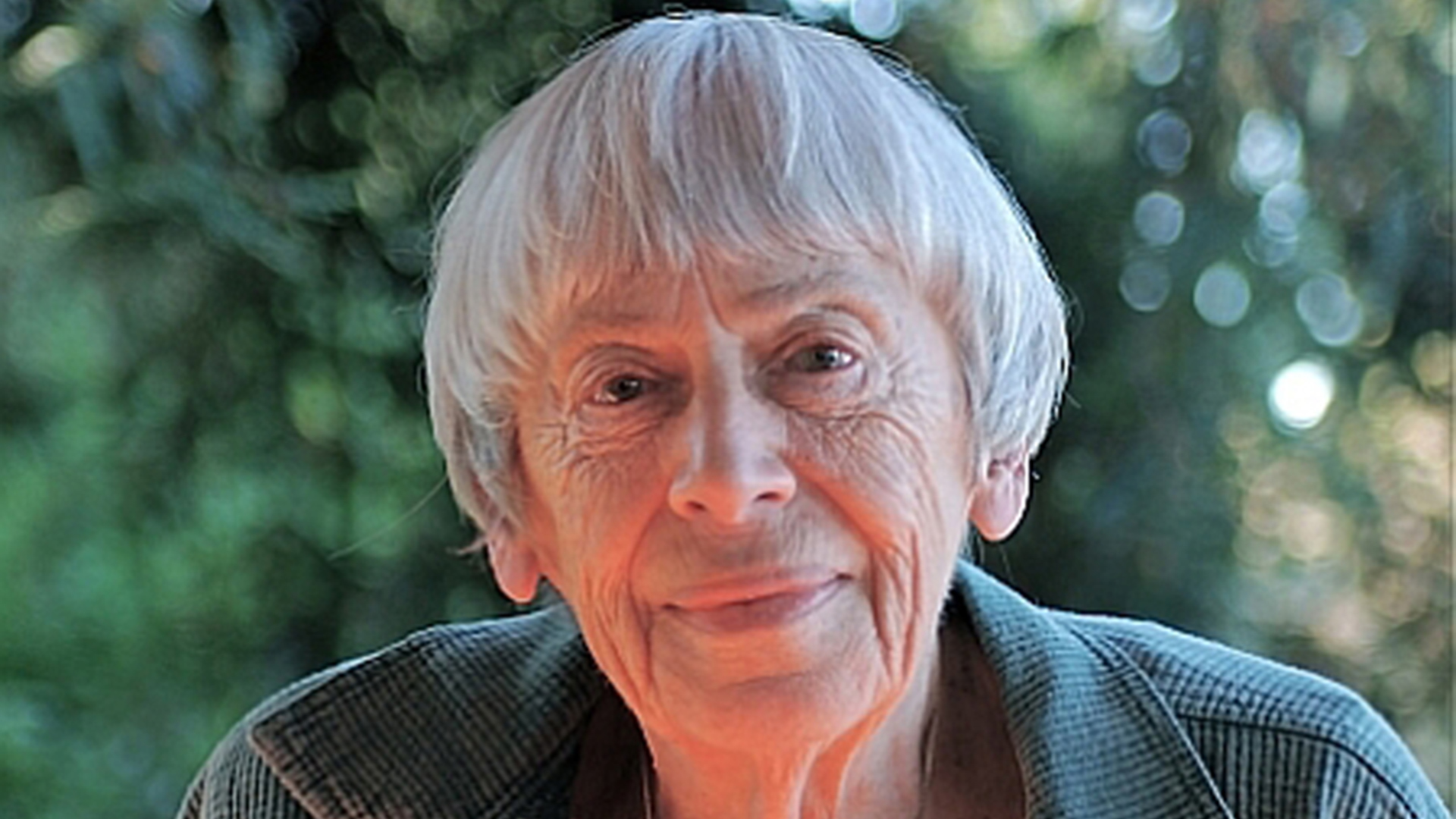

Ursula K. Le Guin. Photograph by OnceAndFutureLaura / Flickr

Another hint of Le Guin’s views about world-reduction shows up in her most famous short story. “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is about a city whose universal joy and prosperity are paid for by a single jailed child’s pain (as the philosophy professors who keep on assigning it will happily tell you, it makes Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” seem like a pleasant stroll through the park). That suffering child is a very potent symbol for what it means to rest the whole world’s burdens on one set of shoulders: Make the single stand in for the general and bad things happen. Individual character’s actions cascade, and at times they ramify; when I act, others make choices triggered by that action, and on it goes. There can be solidarity, yes, arduous, complicated and worth fighting for; to Le Guin, though, collective action is an oxymoron. At moments when crowds mobilize in obedience, or condense into a single all-defining order, an Omelas-like price always has to be paid.

In our interview, Le Guin distinguished between the brilliant intricacy of a Dickensian plot, all whirring interconnected pieces, and the mere brute incidence of story, events that simply happened to happen somewhere and sometime. “The story’s where I go” is as good a manifesto as any for Le Guin. There are always more stories in Le Guin, stories that defy any attempt to seal the novel’s edges and resolve all its diverse occurrences into a single well-ordered machine.

One implication of Le Guin’s anarchist commitment to story over plot is that centers never hold. Le Guin admires the intricate connections Dickens builds between seemingly unrelated parts of Bleak House, but the stories that fill her books attest to her sense that messy old life has a way of refusing the neatness that plot demands. In the later Earthsea books, for example, the orphan Tehanu comes to be linked to Tenar and to Ged not because of a secret amulet or a revelation about her lost childhood, but because the world is a complex tapestry where threads crisscross and then cross again for no particular reason. Even Le Guin’s intriguing friendship with arch-plotter Philip K. Dick never pushed her writing toward the conspiratorial thinking that the Vietnam era spawned among so many radical writers.

Take The Lathe of Heaven, about George Orr, a man whose dreams alter reality. It’s Le Guin’s 1971 homage to Dick (she says so herself) yet it ultimately has a very un-Dick-like appeal. The great Dick novels—The Man in the High Castle, or mindbenders like Eye in the Sky or Time Out of Joint—always make me feel out of control, caught in a tailwind. His paranoid visions of an engineered, terrifying world are helter-skelter, sublime, unsettling—though I love them, they leave me very little room to breathe.

The Lathe of Heaven does play some Dick-like games with time, space, and the unreliability of memory:

A week ago, he had not been the Director of the Oregon Oneirological Institute, because there had been no Institute. Ever since last Friday, there had been an Institute for the last eighteen months. And he had been its founder and director.

This is common ground for Le Guin and Dick: imagination can instantaneously remake reality, so what strikes us as a solid now can alter in an instant to become something else. Recall the most memorable line from her recent National Book Award speech: “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings.”3

In Dick, however, so-called reality resolves ultimately in chaos. The firmament doesn’t hold, and there’s no reason to rely on something other than one’s immediate subjective response to the surrounding whirl of lies, propaganda, and subterfuge. Le Guin, by contrast, proposes that even a world constantly altered by new dreams can be ruled by certain laws. You might think of her as an adherent of Thomas Kuhn’s “structure of scientific revolutions”: for both Le Guin and Kuhn, paradigms change all the time, but the rules by which paradigms change don’t change.

A curious aside in The Lathe of Heaven makes this point elegantly:

There is a bird in a poem by T. S. Eliot who says that mankind cannot bear very much reality; but the bird is mistaken. A man can endure the entire weight of the universe for eighty years. It is unreality that he cannot bear.

It may seem a funny credo for a novelist—is it really fiction you turn to if you want reality?—but it works for Le Guin. If it didn’t feel real, why would you want to read about it?

Because Le Guin is committed to making her readers feel reality’s weight, she asks questions that would never occur to Dick. At one point, George (the man whose dreams can alter reality) wonders if there aren’t others like him out there, also busily altering reality:

“Did you ever happen to think, Dr. Haber … that there, there might be other people who dream the way I do? That reality’s being changed out from under us, replaced, renewed, all the time—only we don’t know it?”

What’s the difference between my dreams altering the world as I look on and yours doing the same thing, only behind my back? Nothing, and everything. Dick succeeds by being out of control; Le Guin, by contrast, is all about the moment when characters themselves turn their heads a little, to think about what relationship their own stories have to those around them.

Le Guin has received her due as a master crafter, as the lyrical chronicler of worlds of the imagination, spaces apart from the world, where children and lingering adults can find an oasis. But the political implications of her anarchist aesthetics go much further than that. There are a few remarkable British novels about life during World War II that refuse to dwell on the war. They dwell instead on civilian life, its ground-level intrigues and mundane betrayals: Henry Green’s Loving is one, Barbara Comyns’s Mr. Fox another. They stubbornly document the persistence of story, the individual idiosyncratic, the persistently free, in a world seemingly overrun and defined by a single, domineering master plot.

You might think of the remarkable run of novels Le Guin produced during Nixon’s reign as a bulwark against what his presidency wrought on the body politic. Under Nixon, nearly a century’s worth of movement toward economic equality in America slowed, stopped, and reversed. 1970 marks the inflection point on the curve that charts waxing income inequality in America.4 Meanwhile, Nixon’s illegal war overseas and dirty tricks at home laid the groundwork for the post-9/11 notion that government’s perpetual war against enemies both external and internal justifies its unsupervised surveillance over all citizens, all the time.

Stalin said that the poet should be the engineer of human souls. Le Guin is the anti-engineer.

To that vision of mobilized might, Le Guin offered a subterranean alternative. President Nixon was the country’s master plotter; Le Guin stood off to one side and instead told its stories. It’s not that we would have been better off with her as president, it’s that her books remind us how little of our world belongs to those who think they rule it. There is no more significant moment in a Le Guin novel than the instant when a character suddenly discovers the larger fabric into which her own thread is woven—that others around her also have names, views, and quests all their own. It happens to Tenar early on in The Tombs of Atuan:

There was something underneath Penthe’s words with which she didn’t agree, something wholly new to her, frightening to her. She had not realized how very different people were, how differently they saw life. She felt as if she had looked up and suddenly seen a whole new planet hanging huge and populous right outside the window, an entirely strange world, one in which the gods did not matter.

There’s sly humor in a line like this, coming from a science-fiction writer whose work it is to create those worlds. I thought of myself as a world, as the world; all around me are other worlds, equally significant, looming equally large.

Even when our actions suddenly make us part of a greater world, the everyday surrounds us, makes even what’s most memorable mostly ordinary. The wall that may free Anarres from the universe is also just a rough-and-tumble mass of gray stones; and the hero “who talked with dragons, and held off earthquakes with his word … lay asleep on the dirt, with a little thistle growing by his hand.” Stalin said that the poet should be the engineer of human souls. Le Guin is the anti-engineer. Precise, evocative, and vivid as her writing is, we should think of it less as architecture than as roadmaking: readers are not settled down by her writing, they are moved by it. Even her most polished books are open-ended and deliberately ragged. The final line of The Left Hand of Darkness is a boy’s stammered question: “Will you tell us about other worlds out there among the stars—the other kinds of men, the other lives?” Le Guin sets readers adrift among those worlds: peripatetic but somehow at home.

- The Tombs of Atuan (Bantam, 1975), p.15.

- Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions (Verso, 2005), p. 271.

- For a transcript and a link to video of the speech, see “‘We Will Need Writers Who Can Remember Freedom’: Ursula K. Le Guin at the National Book Awards,” ParkerHiggins.net, November 19, 2014.

- Facundo Alvaredo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez, “The World Top Incomes Database” (accessed October 5, 2015).