By Sasha Watson

Publishers Weekly

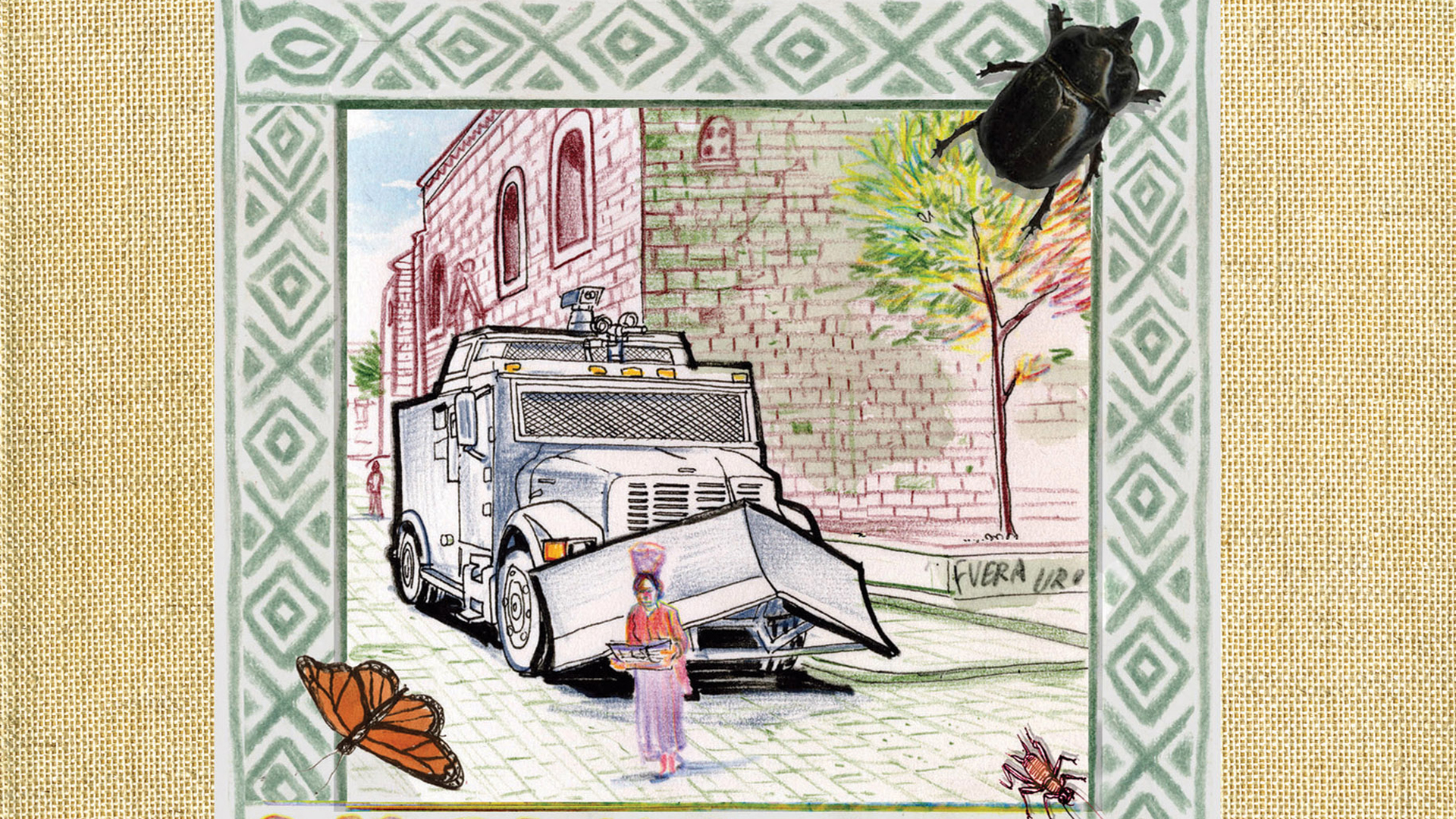

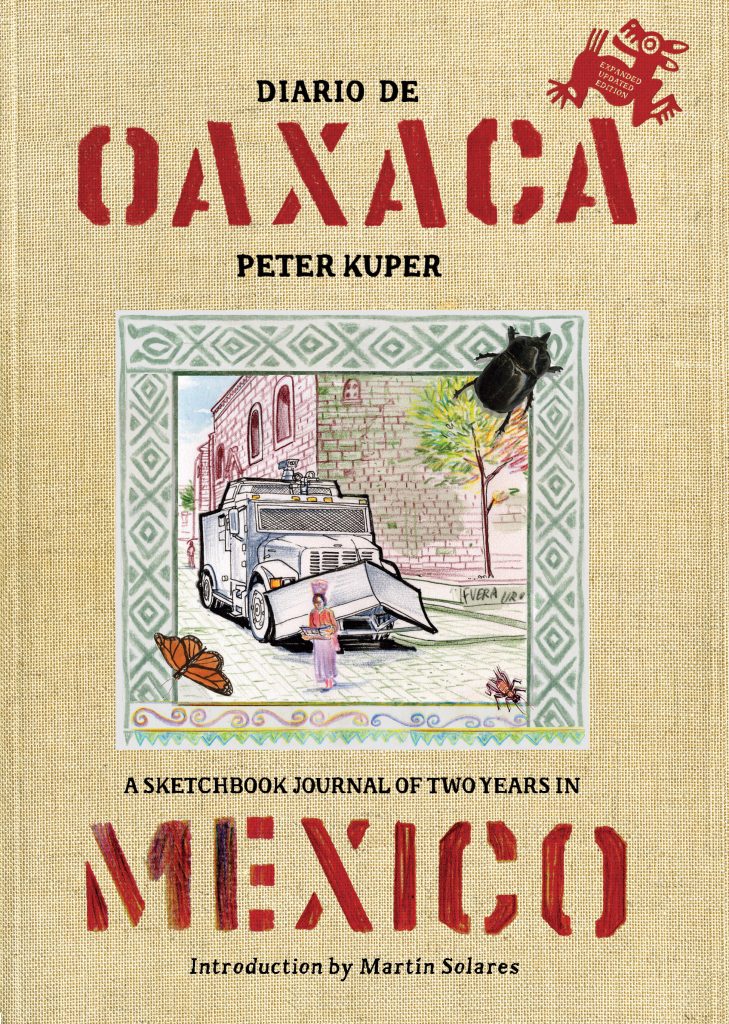

Peter Kuper left the United States in 2006 in search of some peace and quiet. Instead, the award-winning cartoonist found a strike, a government crackdown, and a political storm in Oaxaca. True to the form that led him to co-found the political graphics magazine World War 3, Kuper soon started drawing and writing about what he was seeing around him. The result is Diario de Oaxaca, A Sketchbook of Two Years in Mexico. With text in both English and Spanish, the book is a chronicle in sketches, writing, and photographs, of Kuper’s time in Oaxaca and what he saw during the political turmoil of those two years.

In 2006, the Oaxaca teacher’s strike, which had been taking place annually without incident for years, was the subject of an unexpected attack by riot police sent in by the new governor, Ulises Ruíz Ortíz. Over the months that followed, the situation worsened, resulting in a number of deaths, including those of several teachers and of an American journalist, and the arrival of federal troops in Oaxaca. Combining sharp commentary with sketches that are sometimes impressionistic and sometimes detailed, Kuper leads readers through his life in Oaxaca, showing us what he saw and how he saw it. Diario is a rare and intimate personal account of what it’s like to live through political turmoil. Kuper discussed the experiences and the making of the book with PW Comics Week from his home in New York City.

PWCW: Can you tell me a little about what made you decide to leave the U.S.?

Peter Kuper: Well, the first reason was that we had a nine-year-old daughter, and we wanted her to have a second language. Around ten or eleven the ability to pick up language starts to reduce. Then also, when I was ten my father had a sabbatical, and we spent a year in Israel, and that had a tremendous impact on my sense of the world. Certainly part of it was being burnt out on America under the Bush administration, too. It was shortly after the 2004 elections and my work was very concentrated on political commentary. I was foaming at the mouth all the time, and just thought it would be a good idea to take a break.

PWCW: What made you choose Oaxaca as your destination?

PK: It was a crapshoot, really. We’d thought of going to Spain, but it was clear that there we’d be scrambling like we do in New York, living in an apartment in a city. We’d visited Oaxaca a few times and we were enchanted with it as a place. It turned out to be a really good choice. There’s an incredible artistic community there, with lots of museums and a lot of interesting culture—and then the political explosion was an added bonus.

PWCW: One of the most interesting things about the book is this idea of how news is spread and received. You talk about how difficult it can be to find out what’s happening in a distant country, and even around the corner. How closely were you following U.S. reports of the unrest in Oaxaca and how did these reports compare to what you were seeing every day?

PK: A lot of times the news wasn’t accurate to my experience, and that was one of the things that started to drive me to write. Lots of friends were writing and saying, ‘Get the hell out of there, it’s dangerous!’ but based on our experience, it was okay, even if the reports were somewhat accurate. That’s why I started sending out emails describing what I was seeing, and then later started writing essays.

PWCW: What were the discrepancies between the news and what you were seeing?

PK: I mean, if the newspapers show a photograph of someone throwing a Molotov cocktail onto a bus, it just looks like the place is exploding but that’s not the whole picture. That image is sexier for the newspaper. The threshold of interest is really limited with newspapers, especially now, they are not gonna spend a lot of money reporting on what is essentially a dot on the map for their readers. So the reporter would be in Mexico City which is an eight-hour drive from Oaxaca, which meant that they weren’t seeing things first-hand, so a lot of the reports were really government handouts. If the reporter was there, they were really only there for the most extreme moment of the action. Living there, I was capturing a bigger picture.

PWCW: One of the events you depict in the book is Governor Ulises’s appearance at a radish festival. What’s that all about?

PK: The festival is an annual event that’s gone on for years. People carve radishes and then have three or four hours for the judges to look at them before they go bad. That year there was also a counter radish festival where people were carving federal troops and helicopters out of radishes. That one got shut down after a while. Seeing people use art in response to political situations was really inspiring. I’d been so burned out in the U.S., asking myself, ‘Does art matter? What is its place and importance?’ In Oaxaca, art is so much part of the dialogue and the response. It’s how people heal themselves and announce their resistance. It really seemed that it had value to people in a very real way and it gave me a better feeling about art as an action that has some value.

PWCW: Another art form you talk about in the book is graffiti. How was that used during the protests?

PK: There’s just a tremendous amount of art on the walls in Oaxaca. During the strike and in its aftermath, there were posters, stencils, images and effigies of Ulises Ortiz. The reaction was really vibrant and very visible on the walls, and that energy helped [organize] the strikers. It was very heartening to see that.

PWCW: Did seeing all that activism in response to the crackdown on the teacher’s strike inspire any feelings about activism in the U.S.?

PK: Yes, I mean we had one guaranteed stolen election and probably two in the United States, and the idea that people weren’t encamped in Washington when people camped out for months at a time on cobblestone streets in Oaxaca… We’ve had horrendous events go on that certainly merited taking to the streets, and if we’d had the kind of general public responsiveness there was in Oaxaca, then there would have been more notice taken. Of course there were protests against the Iraq war but somehow we didn’t take it to the next step that made it a problem for the government so they had to respond. I think because the economy was so functional, a lot of people felt anaesthetized to the importance of taking action. But seeing what was happening in Oaxaca really gave me a renewed faith in the impact of art.

Buy Diario de Oaxaca: A Sketchbook Journal of Two Years in Mexico: