By Ernesto Aguilar

Political Media Review

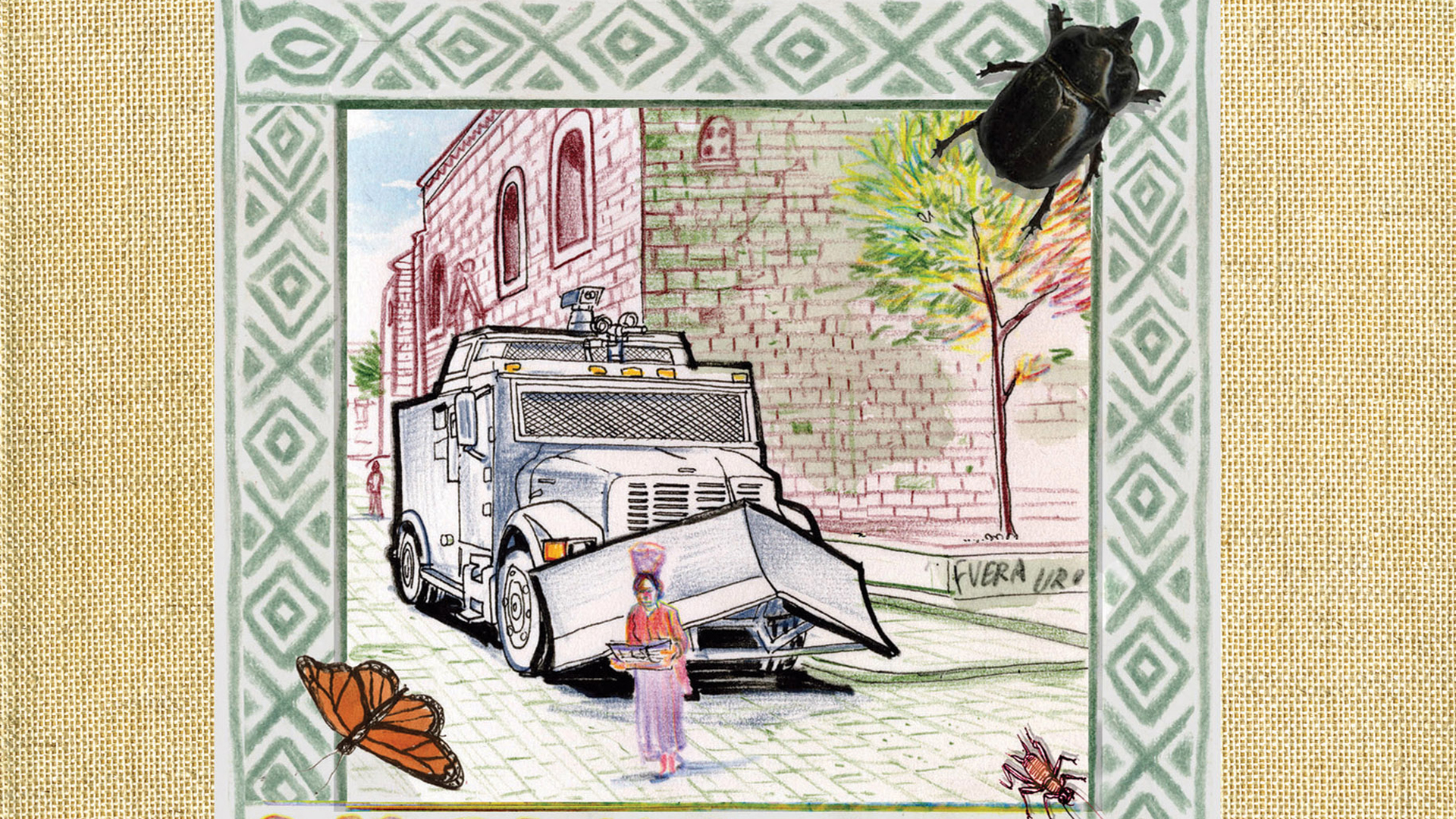

Ostensibly about the recent political strife in the Mexican state, Diario de Oaxaca will likely be far better known for its gorgeous visuals and packaging as a diary, complete with ribbon bookmark. The book, with bilingual versions of the story under the same cover, tells the story of artist Peter Kuper’s life in the community there. However, this book is much more than that.

The 2006 skirmishes and associated campaigns against the Ruiz Administration in Oaxaca are central to Diario de Oaxaca‘s story. The author traveled to Mexico in hopes of breaking away from North American political conflicts as Bush-era crimes continued to mount, and instead found himself in the middle of a mass movement. The document is a first-person account of the tumult from an observer’s standpoint. The historical roots of grievances, the day-to-day impact on Mexicans’ lives, and the determination for a better world are all presented here with compassion and humor. Though clearly partisan, Kuper is hardly an ideologue in the most doctrinaire sense. Stories of Oaxacan forests and bugs dot a theme of resistance, the environment an allegory for the tussle between the powerless and politicians. To hear Kuper tell a story told in dozens of international press writings, Diario de Oaxaca is far more vivid a tale than one might expect, as more than just communities organizing for their survival, but the many unique, creative ways such efforts pop up.

If you are familiar with the teacher’s strike, repression and uprising that is the underlying subject of Diario de Oaxaca, what is likely to keep your attention is Kuper’s fantastic artwork, where everything from drawings of protests and stenciled posters to insects and building interiors grace dozens of colorful pages. Lovingly translated, readers can follow the typeset-style text in English or Spanish. At a time when so many publishers are playing it safe, PM Press takes a tremendous risk offering up what must be a costly item to print at an affordable rate to consumers. Nevertheless, the stunning volume is a treat for readers.

Unexplored in this and many writings on Oaxaca is a complete discourse on why the movement failed. Anarchist sensibilities seized on groups like APPO and the Oaxaca struggle as examples of organizing from below. While arguable at best, such a discourse ignores an important fact: though winning some moral victories, creating the political climate to necessitate the movement’s central demand, Ruiz’s resignation, never happened. Such is largely because organizers could not spark a mass movement that connected with the demand and united around it. Though approached in books like Teaching Rebellion, why it did not happen remains unresolved. Kuper appropriately lionizes the social moment itself in Diario de Oaxaca, but understanding where the movement went wrong remains elusive. As a result, like Kuper’s book, Oaxaca’s struggle is beautiful but ultimately stands as a look at a lost opportunity.

To be clear, Diario de Oaxaca is not an organizer’s manual by any stretch, and expecting a full exchange on movement strategy is perhaps too heady. Still, one cannot but help but wonder what could have been.

Buy Diario de Oaxaca: A Sketchbook Journal of Two Years in Mexico: