By William T. Armaline (Ph.D.) and Damian Bramlett

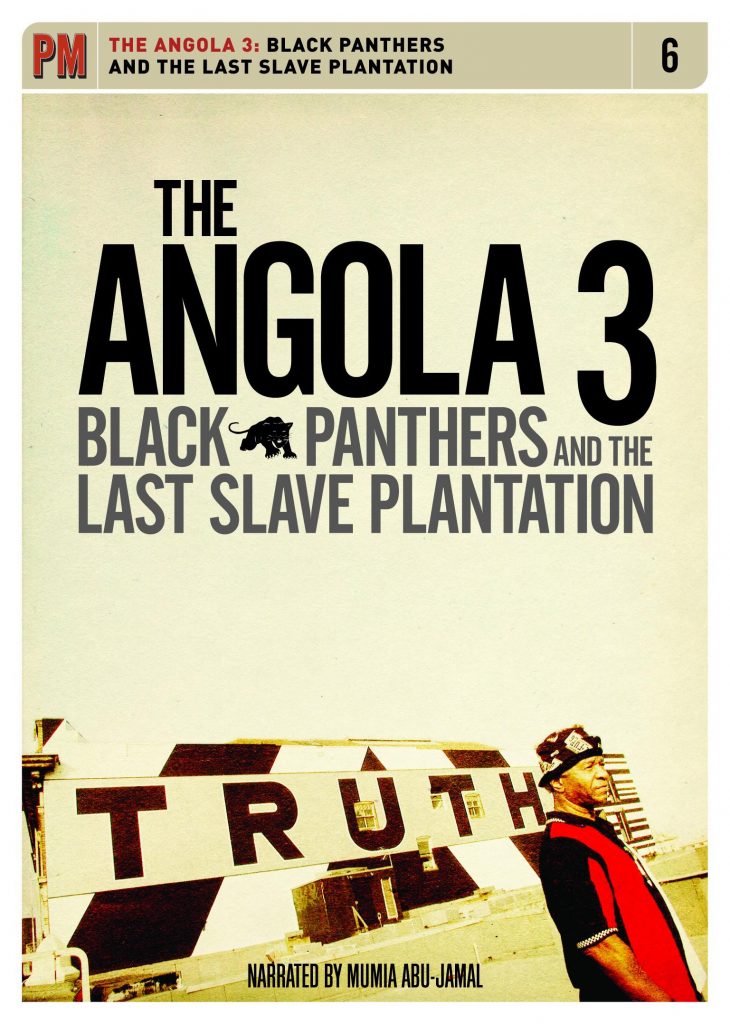

Political Media Review

It is no secret that the United States does not hesitate to incarcerate. While the US only represents 5% of the global population, it cages nearly 25% of the world’s prisoners-approximately 2.3 million people. Of these 2.3 million people, approximately half are African American (13% of US population). Of course, the vastly disproportionate caging and state coercion of African Americans in the US has a long and brutal history. This bloody legacy is made manifest in prisons like Angola, named for the country from which many southern plantation slaves were abducted. The Angola 3: Black Panthers and the Last Slave Plantation details the history of not only Angola prison, but the broader struggle between the US police state and organizations like the Black Panthers over the rights and quality of life of African Americans in the US.

The legacy of slavery is ever present in Angola prison. Before the American Civil War, Angola was a plantation owned by slave trader Isaac Franklin. The prison first opened during the Civil War Reconstruction period and its first warden was a Confederate officer. Vagrancy laws were originally used to imprison freed slaves and ensure their free labor through state coercion. Today, Angola still holds an almost exclusively African American population (over 80%), and operates as a plantation where inmates are forced to conduct backbreaking field labor for the state of Louisiana and its corporate partners. As scholars such as Angela Davis (2003) note of prisons like Angola, the white overseer has been replaced by the prison guard on horseback, the slave replaced by the incarcerated “black criminal.” Indeed, Angola prison reminds us that many things have not changed in a country whose wealth and power was built on the backs of various populations of color-namely African Americans.

In the film, director Jimmy O’Halligan documents the lives of three Angola prisoners and their quest for freedom from incarceration. Herman Wallace, Robert King (AKA Robert King Wilkerson), and Albert Woodfox are the men known as the “Angola 3.” All three were convicted on separate charges during the late 1960’s. King, Wallace and Woodfox would also gain notoriety for starting the only Black Panthers Party prison chapter in 1971. Their connection with the Black Panthers would ultimately lead to their continued incarceration long after their original release dates as political prisoners of the US government.

The viewer is lead through harrowing accounts of how the Angola Black Panthers were the first to challenge prisoner conditions within a severely corrupt penitentiary. Party members would form anti-rape squads, fight for inmates to receive adequate work equipment, and attempt to quell the rampant racism within the prison itself. It is interesting to note that one of the goals of the Angola Panthers was to desegregate inmate populations such that prison officials couldn’t use racism and race baiting to stifle prisoner solidarity and organization. It is now common practice for prisons to segregate inmates by both race and “gang affiliation,” under the guise of “keeping the peace” in the prison general pop. However, as the history of the Angola 3 might demonstrate, such practices are masked attempts to ensure violence and conflict between prisoners in order to prevent any mass resistance movement by inmates against their captors. As it is today, racism was utilized within Angola’s walls as a means of controlling the inmate population. It was this blatant racism that would lead to the extended, and nearly indefinite incarceration of the Angola 3.

King, Wallace, and Woodfox provide their own accounts as to why they were found guilty of crimes they did not commit while in prison. King was “investigated” over a period of 30 years for a murder that took place before he even step foot in Angola. Wallace and Woodfox were both convicted for the murder of a prison guard despite numerous inconsistencies with case evidence. Both men were convicted based on the “eyewitness” account of a (literally) blind informant.

As a result of their convictions, the Angola 3 have spent more time in solitary confinement than any other known person in the U.S. King spent a total of 29 years in solitary, and was eventually released in 2001 after his original sentence was overturned and he plead guilty to a lesser charge. Woodfox and Wallace spent a total of 36 years in solitary until 2008, when they were finally moved to a maximum-security block. The fight for Wallace and Woodfox’s release from Angola continues to this day.

At the same time, O’Halligan should be praised for going beyond the individual struggles of the Angola 3 in the film, where he offers an extended conversation on the broader oppression of social justice activists by the US federal government. Specifically, the film dedicates significant coverage to the covert, insidious operations of CONTELPRO over the last 50 years. It would be impossible to understand the struggles of activists in the 1960’s and 70’s without explaining the lengths to which the state will go to crush internal resistance. This aspect of the film serves as an important lesson to contemporary activists about the roles and tools of the state in the face of great challenge, and is worth noting here.

Jimmy O’Halligan provides a grim and stark view of life on the inside one of the last slave plantations in America. The accounts of radicals and revolutionaries such as Geronimo Pratt, Malik Rahim, Yuri Kochiyama and the narration of Mumia Abu-Jamal add depth and grounded voice to the film. While the pace of the documentary is a bit on the slow side (interview clips are very long), it is full of rich historical accounts. The Angola 3: Black Panthers and the Last Slave Plantation would be an excellent source for those studying systemic racism, prison reform or abolition, and contemporary social justice movements.

Back to Robert Hillary King’s Author Page | Back to scott crow’s Author Page | Back to Ann Harkness’s Author Page