By Tom Keyser

Albany Times Union

April 9, 2009

Robert

Hillary King spent nearly three decades in solitary confinement at the

notorious Angola state prison in Louisiana. As a member of the Black

Panther Party, he and two party members became nationally known as the

Angola 3 — political prisoners who spent decades in solitary confinement

for, they contend, organizing prisoners to improve conditions.

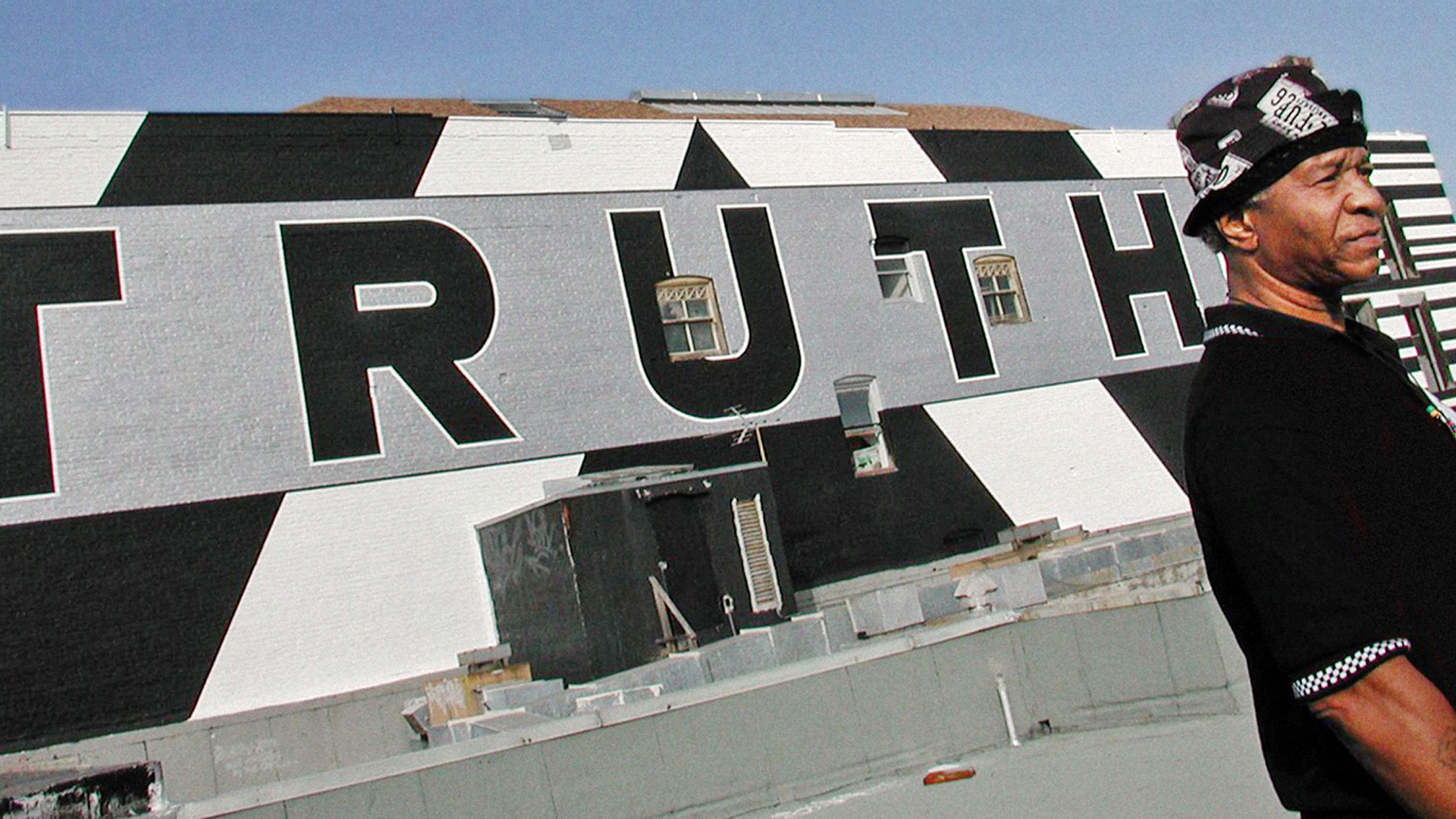

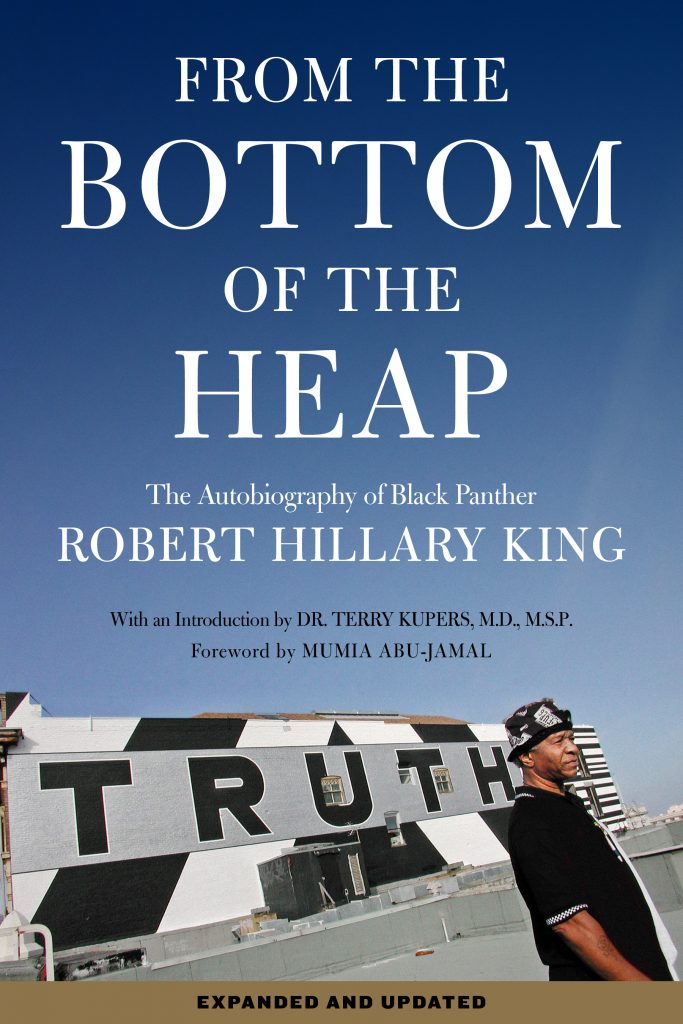

King, 66, will speak Friday at The Sanctuary for Independent Media in Troy in support of his book, From the Bottom of the Heap: The Autobiography of Black Panther Robert Hillary King (PM Press, 224 pages, $24.95).

After becoming a Black Panther in prison and organizing inmates, according to the book’s dust jacket, “prison authorities beat him, starved him and gave him life without parole after framing him for a second crime. He was thrown into solitary confinement, where he remained in a 6-by-9-foot cell for 29 years as one of the Angola 3. In 2001, the state grudgingly acknowledged his innocence and set him free.”

Born poor in Louisiana and abandoned by both parents, King was stealing and fighting on the street by the time he was 11 and serving time in reform school at 15. In and out of local and state prison, he ended up at Angola in 1971 for a robbery he claims he did not commit. There, he says, he was framed for the stabbing death of another inmate.

“Solitary confinement is terrifying, especially if you are innocent of the charges that put you there,” King writes. “My soul still cries from all that I witnessed and endured. … So let’s call prisons exactly what they are: an extension of slavery.”

King recently spoke to the Times Union by phone from his home in Austin.

Q: You write that while in solitary you were allowed out of your cell one hour per day to shower and, sometimes, to go outside into the yard. How did you maintain your sanity?

A: When people ask me that, I tell them, laughing: ‘I didn’t tell you I wasn’t crazy.’ It’s kind of hard to get dipped in waste and not come up stinking.

But I go on to say that I was in prison; prison wasn’t in me. I kind of insulated myself against prison. My political awareness shielded me. Becoming politically aware in the early ’70s, I saw America as being one big prison. All they’d done was take me from minimum custody and put me in maximum security.

But there is some luxury to going insane. I can understand that. Very few things I’m afraid of, but I was scared to go crazy, because I was scared of what they would do to me. I saw them do horrible things to people who, quote, lose their mind or regress into insanity. They were given medications, hosed down with 40-pound, 50-pound pressure hoses. … And it wasn’t just the administration. Inmates took part in the victimization of their own fellow prisoners. You see a lot of things. I couldn’t describe all the things.

Q: Who are the Angola 3?

A: Herman Wallace, Albert Woodfox and myself became collectively known as the Angola 3 after spending decades in solitary confinement. Herman and Albert, both members of the Black Panther Party, were placed there for a crime they allegedly committed, participating in the death of a correction officer back in 1972. It’s since come out that Herman and Albert were framed.

When our story got out in the public, I was subsequently released in 2001 when the courts overturned my conviction of participating in the death of an inmate. Herman and Albert are still in prison. (After 36 years in solitary, reportedly the longest of any inmates ever in the U.S., they were transferred last year to maximum security. When the correction officer was killed, Wallace and Woodfox were serving 50-year sentences, Wallace for bank robbery, Woodfox for armed robbery.) We have a strong legal case, but the state seems to be hanging on for dear life. Albert’s case is in the federal courts, and Herman’s is in the state Supreme Court. We have a civil suit as well.

Q: Are you consumed by anger and bitterness?

A: I don’t know how anybody can go through what I went through and not be bitter, angry and a little crazy. But I can compartmentalize these things that took place in my life. I can dissect them and make an assessment of them.

Prison gave me a focus. The focus is to do my best to make sure that nobody else undergoes the type of thing that I underwent.

Q: What are you doing these days? How are you making a living?

A: When I got released from Angola, I got $10 from the state. That’s all. I went on a few speaking engagements. I was putting out the word for the Angola 3. In some cases, people gave me a little money for doing it. I couldn’t get a job, because when I got out, I was nearly 60 years old. And I had a record.

I got into making candy, something I learned in prison — King’s Freelines, my twist on “pralines”. That’s how I’m able to sustain myself. And I have the book. I have spoken at colleges. Sometimes I’ve received compensation for that. But it’s never much. By no stretch of the imagination am I rich. But I’m not homeless.

Q: What’s the message you’d like readers to take from your book?

A: In the final analysis, America may be heaven for some. But in heaven, there’s some people catching hell. I just happened to be of that segment that caught hell. There’s still people catching hell.

But I guess the main message is one of benevolence. I think we have much more in common than we have differences. I guess that’s the final message.

Tom Keyser can be reached at 454-5448 or by e-mail at [email protected].