By ELIZABETH FLOYD MAIR

Times Union

Sunday, December 27, 2009

Kathy Bricetti writes of calling the police to her own home as a last resort when her 12-year-old son — who’s almost 6 feet tall and has Asperger’s — has three tantrums in one weekend, each more violent than the last. She’s relieved that the officer is “calm and kind to Ben,” and simply talks to him about the consequences of his behavior.

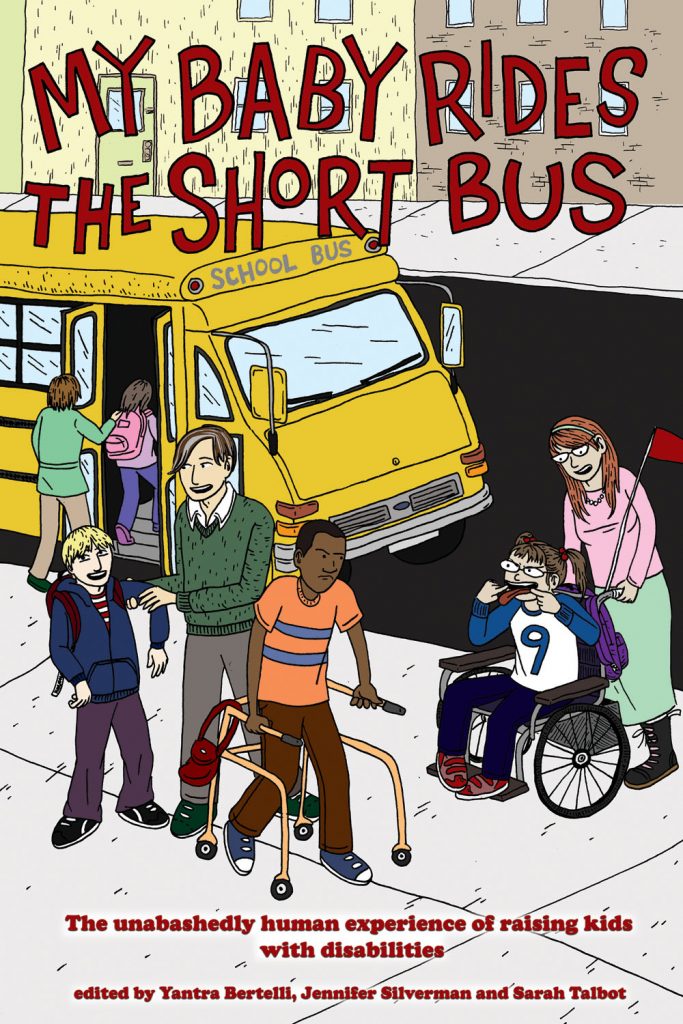

Hers is just one voice in the new anthology “My Baby Rides the Short Bus: The Unabashedly Human Experience of Raising Kids with Disabilities,” whose contributors are parents who are themselves a little bit apart from the mainstream, whether single, gay, older, disabled or perhaps financially struggling.

One of the anthology’s three editors, Jennifer Silverman, (a mom of two kids, one of whom has autism) will be at Book House in Guilderland today for a reading and book signing.

According to Silverman — who spoke recently by telephone from her home in Queens — many of the existing books that offer accounts of parents’ experiences are aimed at an audience mainly of white, upper middle-class readers from intact nuclear families, without a lot of ethnic diversity, and it can sometimes be difficult for readers who don’t fall into those categories to relate. The co-editors of “My Baby Rides the Short Bus” have tried hard to include a much more diverse array of voices than is usually found in print.

Several essayists write with startling honesty about the day they first discovered that their baby would be living with some form of disability. For instance, Andrea McDowell, the mother of a child with dwarfism, writes of her 30-week ultrasound, “My dream of a perfect baby died that day, and nothing would ever bring it back.” Sharis Ingram writes, about parenting two kids with special needs, “I didn’t sign up for any of this when I got pregnant. I thought I was just having a baby.”

Many also describe feeling shock and anger about the brusque, clinical manner of the experts charged with doing the initial diagnosis and evaluation of a child. As Maria June writes, “It was almost as if she was treating Blake like a pathology in and of himself, not as an individual with a complex and unique set of very human needs, the first of which was compassion.”

As Silverman explains on the telephone, “The evaluator just turns around and walks out of that house or that clinic and it’s over for them, but for us it’s just starting.”

The quality of the writing is generally good throughout, although a few writers take the easy route and rely on curse words to express their outrage, which may alienate some readers.

One of the book’s best essays is “Interpreting the Signs,” by Andrea Winninghoff, a hearing mother of a deaf child. She has always been his sign language interpreter, making for a very close relationship: “I am Jonah’s mother but sometimes more importantly, I am the language conduit between him and the hearing world.”

Winninghoff deftly portrays the dilemma she faces when trying to decide whether to enroll 10-year-old Jonah in the residential program for the deaf, several hours from home, that he desperately wants to attend. Deaf acquaintances are shocked at her resistance to the idea (“I was all but called selfish for keeping him from his culture”) while hearing parents are shocked that she would even entertain the idea (“they could never do that to their family”).

Loving her son eventually means letting him learn to communicate freely without her as middle-man and facing her fears of becoming unnecessary to him.

Essayist Nina Packebush points out in “And We Survive” that readers love stories in which kids with severe learning disabilities work hard and grow up to become millionaires “despite being unable to spell or read.” Readers don’t respond as well, she says, to stories “where the underdog remains the underdog and the cute little toddler becomes loud, socially awkward, slightly odd child or teen who will never give friends and family the bragging rights that they feel they deserve.”

A common theme is parents learning to focus on what actually makes the child happy. Maria June adopts a baby with special needs and says that at first she grieved for “possibilities of college and marriage as I have scripted them, fearful that because Mitchell has this or that cognitive or neurological challenge, he would miss out on something I deem necessary for a ‘good life.’?”

There is a great deal of joy too. One parent after another speaks of loving the child just the way he or she is. McDowell, whose child will probably be 4 feet tall as an adult, writes that she secretly loves her small size and that “I would never trade her for a ‘normal’ baby or even her made somehow normal.”

Back to Jennifer Silverman’s page | Back to Sarah Talbot page | Back to Yantra Bertelli’s page